Well, now that it’s loaded in the van, I can reveal the mystery behind the Minneapolis road trip…

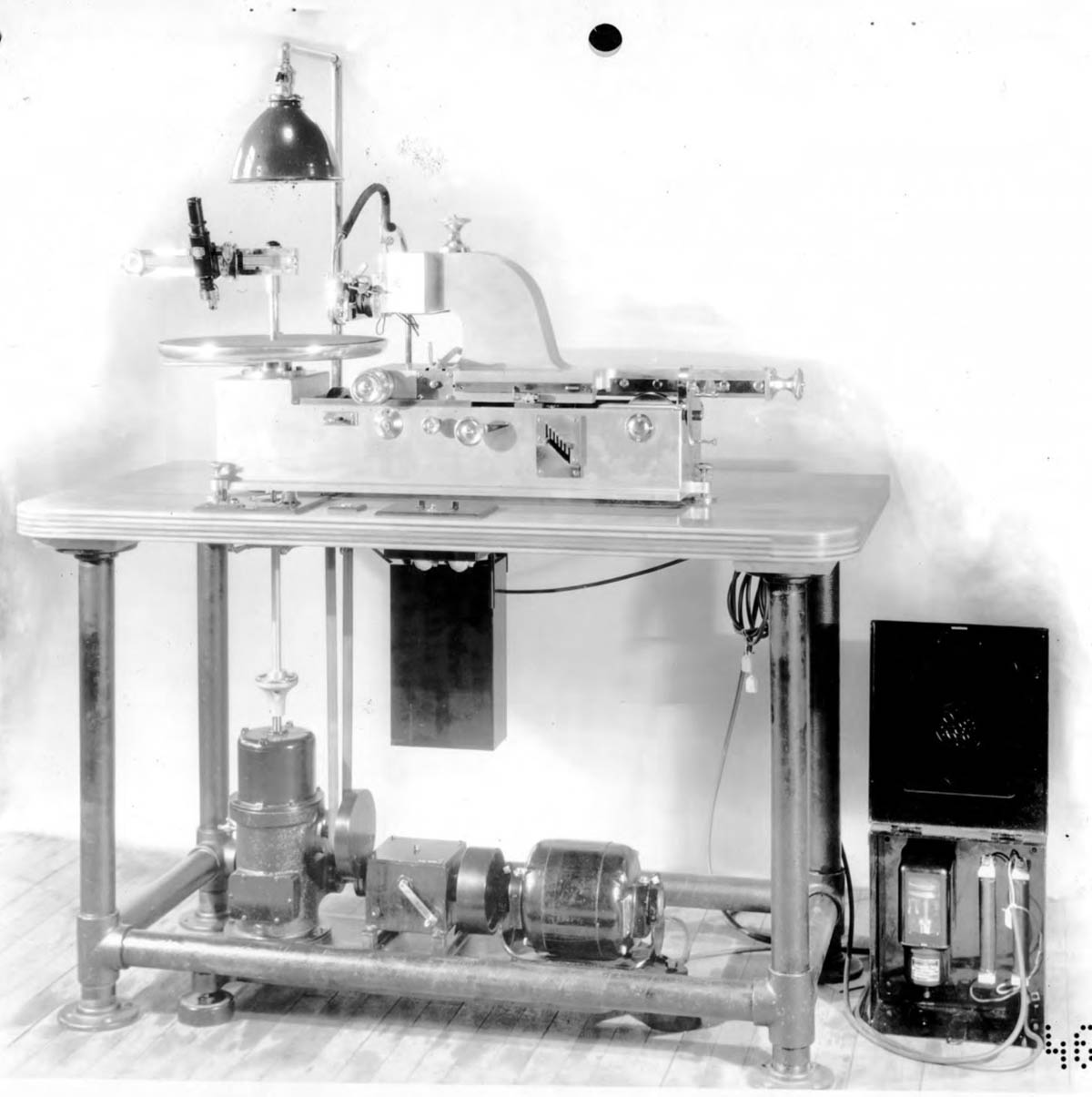

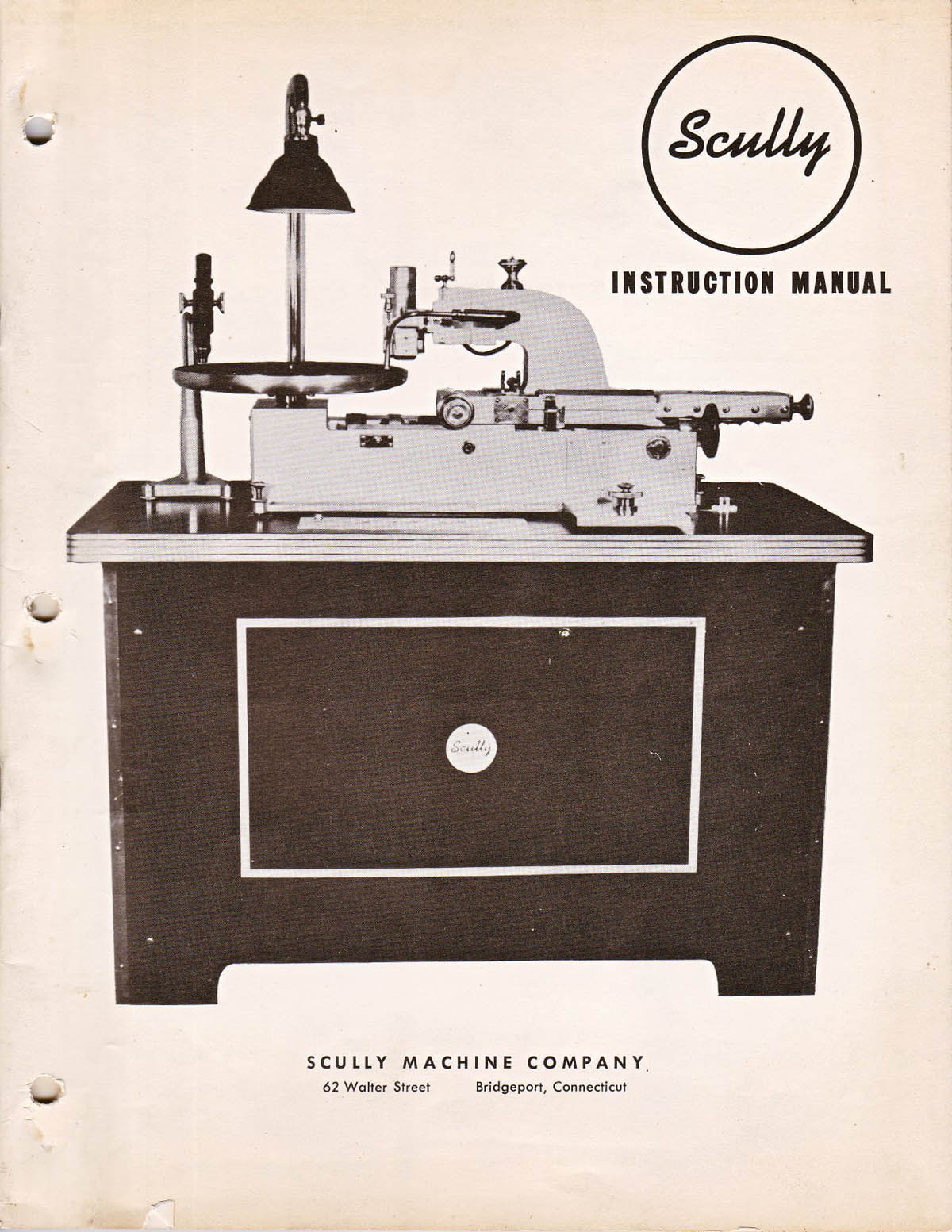

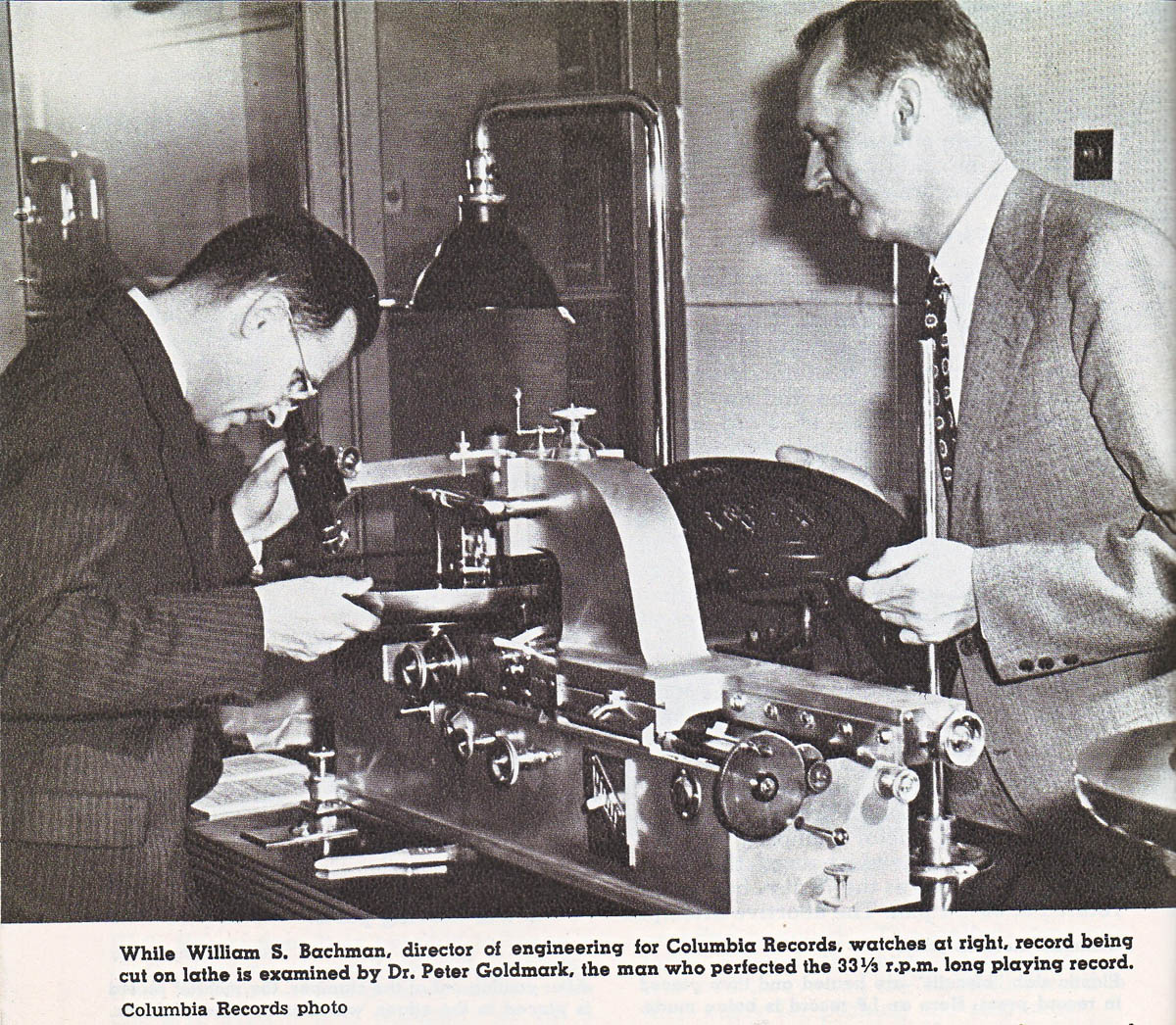

Scully record lathes were the disc recorders that cut most of the records I love: pretty much every American record from the 1930s through the 1960s. 78s. 45s. 33 1/3 albums. Mono. Stereo. Everything from rock ’n’ roll to country, rhythm and blues, jazz, doo-wop, soul, and so much more were recorded on these machines back in the day. All the major labels used them, and the small labels, too. Capitol, RCA, Columbia, King, Starday, you name it—they all used Scully lathes.

Your favorite records were cut on these machines. Pre-magnetic tape, these were simply referred to as “recorders.” Bands would cut their records literally live to disc, in the studio. Scully lathes were gradually replaced by German-made Neumann lathes in the 1960s, and today they are rare—REALLY rare, even though many of the top professional mastering studios still use Scully lathes today that are sixty or seventy years old, because they were top gear back in the day and they are still top gear today.

There were around six hundred Scully lathes made, going by the serial numbers, but virtually all of the ones made before World War II were melted down for the war effort, and many of the ones made after the war were junked after vinyl sales tanked in the 1980s and 1990s. Today there are around twenty-one working Scully lathes known to exist. There are perhaps another ten or fifteen out there that are known to exist but aren’t working, making a total of less than forty Scully lathes left in the world. People know where they are. There is one in China. There are a couple in South America. There are several in Europe. A dozen or so mastering facilities in the United States use them today. But there aren’t many Scully lathes out there.

Some of you may have followed the trials and tribulations of my own Scully lathe restoration the last eleven years. I bought it disassembled, in a bunch of boxes, and set out on a quixotic crusade to restore it because of a lifetime dream of mine to cut records. I thought to myself, hey, I really want to cut records! How hard could this be?

Scully lathes were made one at a time, much like little custom handmade automobiles. I’m imagining a small group of machinists slowly putting them together, maybe ten or fifteen lathes per year, like something out of a black-and-white newsreel from the 1940s. They didn’t change dramatically from 1930s production models to 1960s production models, but—each one was made by hand. So when I started putting my lathe together, I ran into crazy obstacles. The parts from my disassembled lathe came from about four different lathes (there were four different serial numbers on the parts—a stock Scully lathe would have matching serial numbers on every part). None of the mounting holes lined up on ANYTHING, because each lathe was made by hand, apparently without concern that someone would try to fit parts from a different machine on it decades down the line. There were some parts missing that proved impossible to find, and I had to have new parts fabricated.

That’s when the real world of hurt came in on my lathe restoration. I’ve literally spent ten years and several thousand dollars getting stuff worked on by a very good machinist in Los Angeles who works on record lathe stuff. I’d discover something wrong or missing, I’d go to Keith, it would be eight months to a year before I’d get the part I needed. Then I’d discover something else wrong. I’d go back to Keith, wait another eight months to a year. Repeat that process, over and over.

It got really frustrating. My lathe is still sitting at home, about 99% done, but in eleven years it hasn’t cut one record. It hasn’t been fired up one time. It has been damn frustrating. Most recently, I found out that my two lead screws, the heart of the lathe, designed for one lead screw to cut records from the outside in and one to cut records from the inside out….somehow are inexplicably both inside-out lead screws. Unless I wanted to cut inside-out records. Which I don’t. So I’m waiting on a proper outside-in lead screw at Keith’s machine shop, but he says it will be about a year wait. Another year…man, I don’t have that many years left on the planet!

When I first got my lathe eleven years ago, I found a guy in Minneapolis who had a Scully lathe. He had got it in a gear swap in the early 1990s and used it to cut records for his progressive space-rock band. Eight or nine years ago, when I came to Minneapolis for some shows, I went over to see his lathe, and I took a bunch of photos and video of it to aid in my restoration (with only twenty-one working Scullys in the world, I set out to see as many of them in person as I could). The nice thing about this Scully was it wasn’t used in a professional mastering studio. It was just kind of squirreled away. I filed it away in the corner of my mind.

A few months ago, I called the guy to see if maybe, just possibly, he had a spare lead screw he would sell me. He said he didn’t. But after a long pause, he told me he would sell his lathe, if I was interested. And the price wasn’t out of line.

Now, trust me, there is no one more aware of the fact that I already have one of the world’s remaining Scully lathes at my house, taking up a lot of room. But it doesn’t work yet, and I couldn’t tell you exactly when it will. It might be next year, it might be five or ten years from now.

In the twenty years I’ve been paying attention, I’ve never seen a complete working Scully lathe come up for sale. They just don’t turn up, and when they do, the lathe guys are on it. Nothing ever gets offered to a “civilian” like me. I got that feeling I have felt numerous times in my life—I can’t let it slip through my fingers. I have to make this happen. So I sold some stuff, horse-traded some stuff, got some money together, and flew to Minneapolis to buy the thing in January. And this week, I drove from California to Minnesota in a rental van to load it up and drive it home.

Although some people might consider eleven years restoring something without it working to be a failure, I just think about that bit of showbiz advice that Cliffie Stone gave me many years ago: “Figure out a way to turn your failures into successes.” Cliffie’s own story was when he began shooting his live television show Hometown Jamboree in the early 1950s, a train would go by the El Monte Legion Stadium during the broadcast every week and shake the building and the television cameras. It drove him crazy, until he realized he could simply make it part of the act. From that moment forward, when the train came during the show, Cliffie would announce “THE TRAIN’S A-COMIN’!” and when the train passed by, he told his cameramen to shake the cameras even more, to make it seem like a really wild event for the audience. The shtick turned out to be a hit with fans, and a favorite part of the show. He turned his failure into a success. That story stuck with me.

So even though I have spent eleven years restoring a lathe that still doesn’t work, I learned every little part on the Scully lathe, from the tiniest spring steel clip inside the gear mechanism to the history of the various drive motor units used over the years to the minutiae of the Westrex cutting heads and cutting amplifier systems. I got a hard, blistering, frustrating education, but it was an education. I learned how all the various parts of the Scully lathe worked. And now I feel like I’m ready to take this working Scully lathe and start cutting some goddamn records. Time to get it home and set up and start doing what I set out to do.

The funny thing about this lathe I just got is that the guy didn’t really know the provenance of where it came from originally. As we took it apart today, underneath the table was an address label for a disc cutting studio in Calabasas, California—the San Fernando Valley! So this lathe is coming back to Southern California, where it used to live. It all just feels like it was meant to be. Hey, I’ve turned my failures into a success!