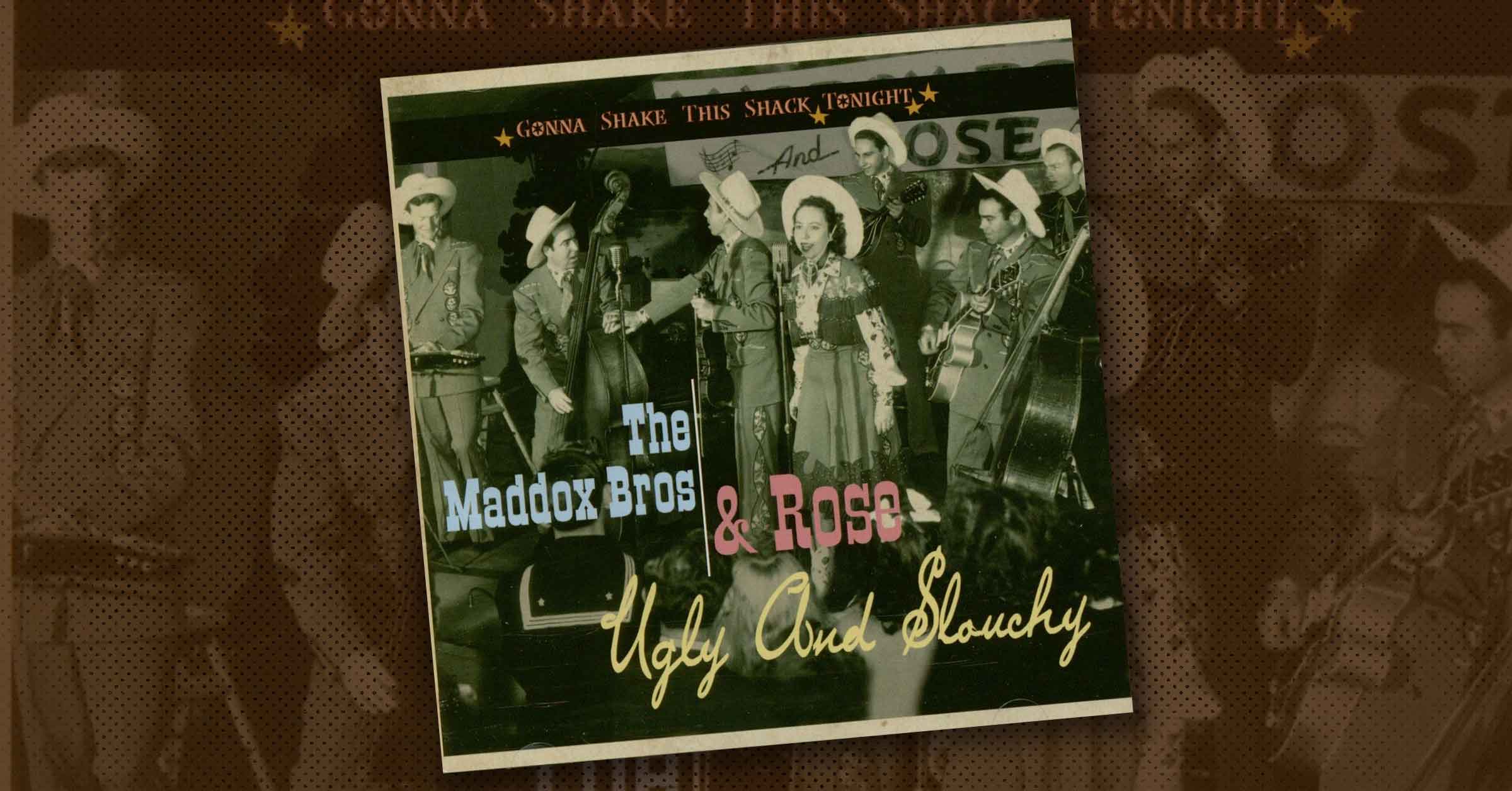

Liner notes for Maddox Brothers and Rose, Gonna Shake This Shack Tonight: Ugly & Slouchy , Bear Family Records

Originally published in 2006

They were loved by Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley; it would be hard to come up with a musical group more influential than the Maddox Brothers and Rose in the bawdy birthing of rock and roll music in the 1950s.

What is true about the Maddox Brothers and Rose is that their music, a rough and rowdy blend of hillbilly boogie, western songs, and medicine-show hokum, was a powerful spark of inspiration to the first wave of rockabillies and rock and rollers. From their wild stage costumes to their fleet of Cadillacs, the Maddox Brothers and Rose were rock stars before there was such a thing as a rock star. In what has become a most ironic twist of fate, their recording of “The Death Of Rock And Roll” (included here), meant to parody Elvis, has become their most revered recording in rockabilly circles, rightly given credit as an excellent example of the genre!

The compilation presented here is a selection of the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s hottest recordings for Columbia Records, from their very first session in January 1952 to the last secular recording the group ever did in August 1957 before Rose went solo and the family assemblage disbanded. For rockabilly and hillbilly boogie fans, this is the ultimate collection to have. If you want a more complete representation of what the Maddox Brothers and Rose were really about, check out the Bear Family box set The Most Colorful Hillbilly Band in America (BCD 15850), a four-CD collection of their entire Columbia legacy. If you are the type of fan who wants to hear absolutely everything, their earlier recordings from the 4-Star label (which many consider their best) and their live radio transcriptions have been expertly reissued by the Arhoolie label. Bear Family has also released an excellent box set, The One Rose (BCD 15743), which contains Rose Maddox’s entire solo output from the Capitol years of the late 1950s and 1960s.

The Maddox family saga has been told and retold many times, and it is the stuff of legend. As writer Robert K. Oermann put it, “They didn’t have to read John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath; they lived it.” The Maddox clan (and, indeed, they were more a clan than family) hailed from the scrubby mountain area of northeastern Alabama, where their father Charlie and mother Lula sharecropped and set up camp near the small town of Boaz (only thirty-nine miles away from Section, Alabama, birthplace of the Louvin brothers, and only seventy miles from Hank Williams’s birthplace in Mount Olive West, Alabama). Cliff was the eldest son, born in 1912, followed by the senior sister, Alta, in 1914; Calvin followed in 1915, Fred in 1919, Don in 1922, the littlest sister, Rose, in 1925, and finally baby brother Henry in 1928. The family lived in the poorest imaginable conditions, though it was not atypical for that economically depressed area. They led a hand-to-mouth existence working the land, without the benefit of running water or electricity.

What differentiated this family from the tens of thousands of similar poor, southern families of the era was the matriarch of the Maddox household. Lula Maddox was quite simply unique among her peers, ruling with a dominance that extended not only to managing the financial aspects of the family business, but also to discouraging her children from marrying or leaving the fold. Lula came up with the idea, mostly from reading dime-store novels, that the family should move to a mythic place called California, where gold literally grew on trees, and she held fast to this notion for years until she finally convinced the Maddoxes to venture west in 1933. Predating the enormous Okie migration by several years, the family headed west with $35 that they had made from selling the few possessions they owned. Hitching rides, walking, and chiefly riding in boxcars with hoboes and drifters, the Maddoxes made it to Los Angeles in a few weeks, with days off spent working odd jobs to feed the family sufficiently for the next section of the journey. From there they headed north to satisfy Lula’s dream of working what she called the gold fields of Sonora.

What they found instead were more impoverished families like themselves, all looking for the promise of a better life. The Maddoxes were soon living in a Depression-era phenomenon known as the Pipe City of Oakland, a construction area with many large drainage culvert pipes where families set up living quarters within the curved sections of unused pipe. A famous picture from this time was published in the Oakland Tribune on April 11, 1933: a Dust Bowl sepiatone showing the five children with Charlie and Lula and a caption that read “Family Roams U.S. for Work.” From here the family settled into a migrant farming lifestyle around their next adopted hometown of Modesto. Now known as “fruit tramps” and wrongly called “Okies” (a derogatory designation on a par with the term “nigger” at that time), they slept in tents on the cold ground while following the fruit picking harvests around central California’s San Joaquin valley.

While music had always played a role in their lives (being one of the few free forms of entertainment available to dirt-poor laborers like the Maddoxes) it took the wily mind of middle son Fred Maddox to envision the family as a professional musical outfit. They had little more than a single guitar among them, with no experience playing as a band, when Fred decided the way to escape manual labor was to go professional as a music group. With Lula’s help, Fred approached the Rice Furniture Company in Modesto about sponsoring the Maddox Brothers to perform on the local radio station KTRB. Fred was always able to charm his way into any situation, and he sold the owner on sponsoring the group—with one hitch. The owner insisted that the group had to have a female singer. Without missing a lick, Fred promised him that their younger sister, Rose, was the greatest female singer in the history of music, and they got the job. What he had neglected to mention was that Rose was only eleven years old and had done little singing besides some hollering out in the fields and around the campfires!

Nonetheless, the group debuted in 1937 on KTRB and almost immediately found success, receiving more than ten thousand cards and letters within their first week on the air. The Maddox Brothers and Rose formula was cast from the start and changed very little until their breakup in 1957. Their professional persona is easily explained, as the family band was simply an extension of who they were in real life. There was no pretension or any element of a manufactured image. Their authenticity was a distinction that made them extremely popular with common people. The fans knew that this group was just like them—sang for them and about them.

There was one exception, though, that perhaps defines the difference between country music and folk music. While the Maddox Brothers and Rose played simple music for simple people, they knew from the start that their audiences wanted to see a show and to be entertained. You wouldn’t see the Maddoxes wearing tattered peasant clothes a la Woody Guthrie and riding in a Model T for folky schtick. Instead they became known as the most colorful hillbilly band in America, wearing the fanciest Western suits ever created, playing the finest, top-of-the-line musical instruments, and driving brand-new, shiny cars. It was a masterful stroke of show business, and the Maddoxes would create a wave of excitement wherever they went.

The group began recording for Bill McCall’s 4-Star record label in 1945. McCall was a legendary figure in the record business, most famous for refining techniques of nonpayment and avoiding royalties, which resulted in more than one artist pulling a gun on him (and which continues today, with the 4-Star legacy poorly managed due mostly to fear of royalty lawsuits). The Maddox Brothers and Rose struck a deal with McCall that was fine with the group, largely because it resembled the barter system that they had grown up with as sharecroppers. McCall would give them as many 78 RPM records as they desired, which they could then sell at shows. It cost McCall barely anything to give them free product, and the Maddox Brothers did quite well by selling the records as merchandise.

The group during this period was augmented by several outside musicians, including legendary guitarist Roy Nichols, who was a young teenager when he played with the Maddox Brothers and Rose (and who would go on to fame as a guitarist for Wynn Stewart, the Farmer Boys, and of course most notably Merle Haggard), another well-known California guitarist Gene Breeden, and steel guitar player Bud Duncan. The Maddoxes’ musical ability was still somewhat limited, and having these musicians on their records and at their live appearances added fullness to their sound. Eventually, Mama Maddox would decide that having outsiders in the band was a bad idea, and by the early 1950s the band was made up of family members only (though occasionally accompanied in the studio by the likes of Joe Maphis and others).

The Maddox family saga has been told and retold many times, and it is the stuff of legend. As writer Robert K. Oermann put it, “They didn’t have to read John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath; they lived it.”

By the time that the Maddox Brothers and Rose signed with Columbia in January 1952, they had built up their reputation and fame to a point where they were considered the most popular hillbilly act on the West Coast. Although their sound was a lot more primitive than most of Columbia’s roster, their popularity couldn’t be denied and producer Don Law decided they met the criteria to be on the label. The Columbia material ran the gamut, as did the group’s live shows, from pure hillbilly to western group singing tunes, novelty songs, ballads of tragedy, and fiery hillbilly boogie. It was as if they were throwing something against the wall to see what would stick. On this compilation we have chosen to feature most of the uptempo hillbilly and boogie-woogie material, starting with a song from their very first session, “I’ll Make Sweet Love To You,” which is a great example of what the Maddox Brothers and Rose were really about—pure hillbilly chaos—from the group cutting up and laughing on mic to their ragged-but-right group playing, anchored by Fred’s frantic (and quite rockabilly sounding) slap bass.

All the tracks from the early 1950s included here are wonderful examples of the same formula, from their cover of the Carlisles’ “No Help Wanted” to one of Rose’s first solo recordings, “I’m a Little Red Caboose” (recorded in Nashville with much of Hank Williams’s band) and other Rose compositions such as “You Won’t Believe This” and “Fountain of Youth.” In 1955 the group recorded a session at Jim Beck’s studio in Dallas without the aide of any outside musicians, which offers a great glimpse into what they must have sounded like live. “I Gotta Go Get My Baby,” “No More Time,” and their autobiographical “I’ve Got Four Big Brothers (To Look After Me)” are all masterpieces. A Rose solo session from February 1955 illustrates what a musical pioneer she was, covering Ruth Brown’s “Wild Wild Young Men” and oozing pure rockabilly (with hot licks courtesy of Maddox alumni Roy Nichols on guitar and future guitar-string magnate Ernie Ball on steel guitar). A December 1955 session with Merle Travis on guitar produced the rocking “Hey Little Dreamboat,” firmly establishing Rose as the first female to cut rockabilly music.

The brothers’ most fondly remembered session came in August 1956 with three of their best numbers, “Ugly And Slouchy,” “Paul Bunyan Love,” and “The Death of Rock and Roll.” “Ugly and Slouchy” is Fred Maddox’s finest moment, an ode to the joys of having an unattractive mate because “there’s never any fear of her loving someone else.” Fred’s wild bass slapping dominates all three songs, most notably on the frantic “The Death of Rock and Roll.” As previously mentioned, the Maddox Brothers’ farce, meant as a parody of rock and roll, has since become their best-loved tune in rockabilly circles, and with good reason—the Maddoxes could rock with the best of them. Rose cut some more great rocking material in Nashville in November 1956 with Joe Maphis from the West Coast tagging along on guitar. That session included another rockabilly killer, the phenomenal “I’ll Go Steppin’ Too. “

The last Maddox Brothers and Rose sessions took place in the spring and fall of 1957 and again showcased some of their finest moments, including the favorites “Short Life and Its Troubles,” “Dig a Hole (In the Cold Cold Ground),” “Stop Whistlin’ Wolf,” and “Let Me Love You,” all considered Maddox Brothers standards today, as well as an odd but groovy cover of Mickey and Sylvia’s “Love Is Strange” with nice, bluesy guitar licks courtesy of Billy Strange. Though the Maddox Brothers would do one more session with Rose in February of 1958 (a gospel album that became their only LP release on the label), the writing was on the wall for the group that had been playing together since the late 1930s. Rose had been recording solo sessions for several years, and the brothers had grown tired of living under Mama Maddox’s extreme control. When Columbia dropped the group and Rose in 1958, the brothers and their sister went separate ways. Although Cal and Henry would occasionally record and tour with Rose, the family group officially disbanded and never again recorded together. Fred Maddox attempted to keep it going with Henry’s wife Lorretta (billed as the Maddox Brothers and Retta), and after the public rejected the new lineup he became a local Los Angeles-area raconteur, opening several clubs (including Fred Maddox’s Playhouse in Pomona) and running the Flat-Git-It record label, releasing his own solo recordings as well as other LA-area country acts. Don Maddox enrolled in agricultural college, moved up to Oregon, and quit the music business.

Rose continued her life as a star, with Lula continuing the stranglehold on her daughter, never allowing her to have a personal life (Rose’s personal life was full of disastrous relationships, including a marriage and a son, Donnie, that Lula would not allow Rose to raise—a story in itself). The focus was always on the career and the next recording session or concert down the road. Rose was signed to Capitol Records in 1959 and had a very successful run with the label, recording a hit duet with Buck Owens (“Mental Cruelty”) in 1961 that brought Owens great notoriety and established him as a true up-and-coming star. In addition, Rose recorded a phenomenal bluegrass album with Bill Monroe that is to this day considered a benchmark of the genre.

Lula died in 1969, collapsing in Rose’s arms. Rose continued the only life she had ever known, playing small beer joints and country music halls throughout the country, touring with her son Donnie on bass and guitar. She had grown closer to him in his teenage years, but he died in 1982, another death that broke Rose’s heart, prompting a gospel album in tribute to her son, A Beautiful Bouquet. Rose never stopped touring, save for time spent recovering from a heart attack in 1981. This author was fortunate enough to back up Rose at a folk festival in San Diego in 1995, and her voice was as strong and feisty as it was when she was a young girl.

Rose continued to record after her Capitol days for small labels, including Starday, Cathay, Portland, Takoma, and Varrick, until the Maddox Brothers and Rose legacy finally began to receive its due. Arhoolie Records began an excellent series of reissues of early Maddox material as well as several well-received new albums, including 35 Dollars and a Dream, which was nominated for a Grammy in 1996!

Rose died in April 1998, after Fred in 1992, Henry in 1974, and Cal in 1968 (Cliff had died years earlier in 1949). Today Don “Juan” Maddox is the only surviving member of America’s Most Colorful Hillbilly Band, still living on the family ranch outside Ashland, Oregon.

This collection is the ultimate collection of the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s rockabilly, hillbilly boogie, and “flat-git-it” country recordings. In the words of Billy Miller, if there was any justice in the world, the Maddox Brothers and Rose should have been rich enough to live in a mansion—with Kenny Rogers forced to be their gardener. We hope you enjoy this collection. There will never be another group like the Maddox Brothers and Rose.