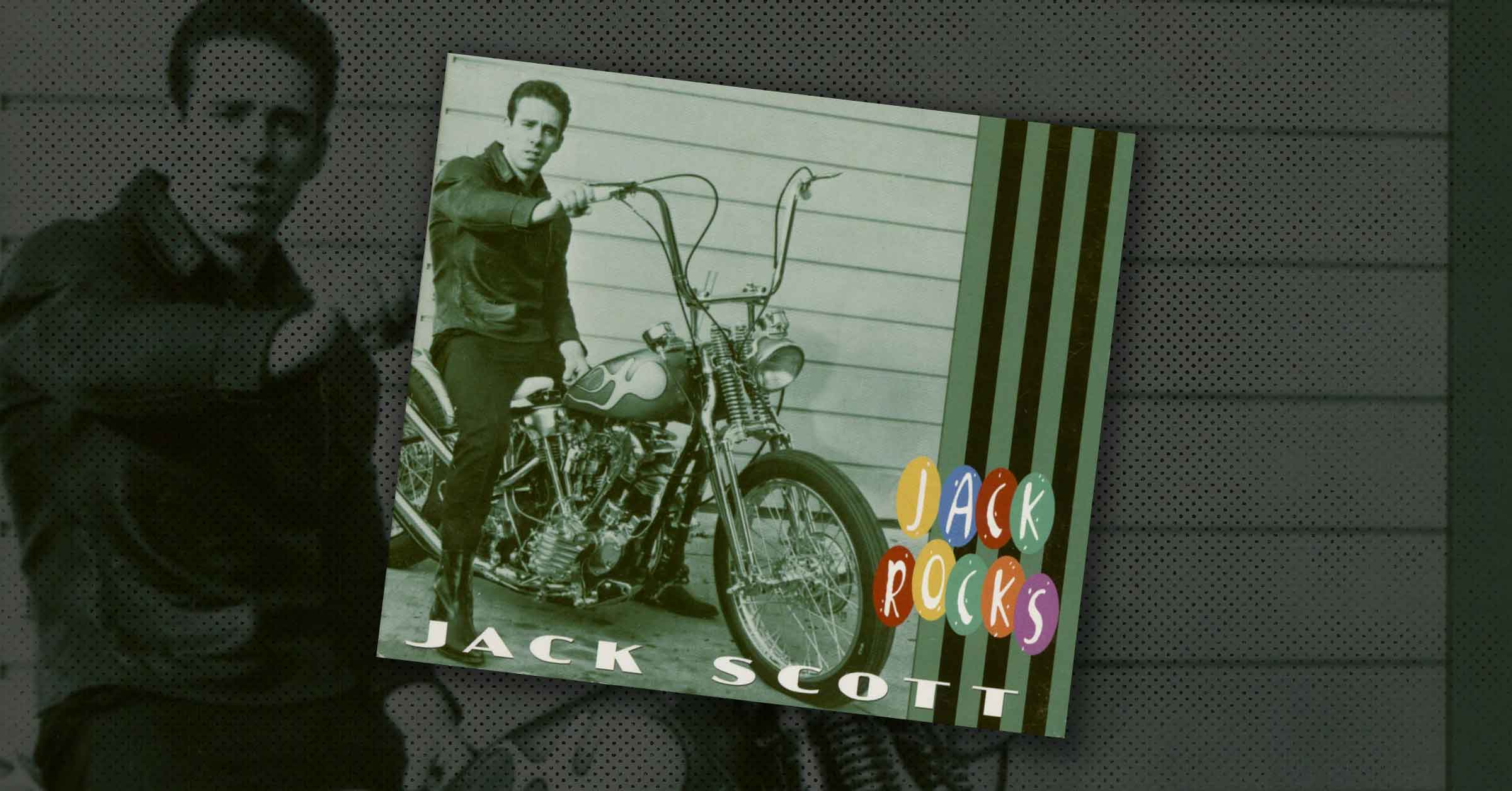

Liner notes for Jack Scott, Jack Rocks, Bear Family Records

Originally published in 2006

Rock and roll and its warped cousin, rockabilly, were mostly the property of the southern states in the 1950s, with nearly all the big stars coming from within driving distance of Memphis. It makes sense, however, that the city of Detroit spawned a real, honest-to-goodness rock and roll legend, Mr. Jack Scott of Hazel Park, Michigan.

While Detroit was as far north as any major American city, the population was for the most part made up of hillbillies and black Americans who had moved up from the southern states to work in the automobile industry. From the 1930s until today, this diversity has made Detroit a spawning ground for many interesting musical hybrids: John Lee Hooker, Little Willie John, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters in the R&B field; Casey Clark, Lonnie Barron, and the York Brothers in country-western; the entire Motown Records clan and Atlantic Records superstar Aretha Franklin in soul; and of course a whole slew of gritty rock bands from the MC5 to Iggy and the Stooges to present chart darlings the White Stripes. Even present-day rap-rock star Kid Rock is a Detroit mix of black hip-hop and redneck country influences.

Somewhere in that mix came Jack Scott. He was a Canadian-born Italian, real name Giovanni Dominico Scafone Jr., who was raised in Windsor, Ontario, just over the border and across the bridge from Detroit. At the age of eleven his family moved to Hazel Park, Michigan, a hillbilly (read: white) suburb of Detroit. His father was a musician and played guitar for the kids (Jack was the oldest of seven children), putting a guitar in his hands at the tender age of eight. He loved country music and would strum his guitar around the house and listen to country music on the radio, dreaming big dreams about the Grand Ole Opry and Nashville. During his teenage years, Scott worked a number of odd jobs while continuing to play guitar. He formed a local hillbilly band called the Southern Drifters (an interesting name for a band from Michigan!) at eighteen.

Scott was always obsessed with music. He imitated Hank Williams, Webb Pierce, and many others. His aspirations were fully formed at an early age, and in fact he changed his name from Giovanni Scafone to Jack Scott at the suggestion of local WEXL disc jockey Jack Eirie, who said he might be more successful with a more easily pronounceable, more anglicized name.

When Elvis came along everything changed, and like many other teenagers of the mid-1950s Scott realized he might have some potential with the new sound of rock and roll. The Southern Drifters began working Elvis and Bill Haley songs into their country repertoire. It’s doubtful, though, that Scott had any idea that he would soon be at exactly the right place at the right time—a place where a good-looking, greasy-haired Italian kid who played the guitar could be a famous rock and roll musician—but that’s exactly what happened.

In early 1957 the group decided one night after a dance to rent some late-night studio time and laid down two tracks, “Baby She’s Gone” and “You Can Bet Your Bottom Dollar.” “Baby She’s Gone” was influenced heavily by Elvis’s version of “Money Honey” but has proved to be a classic in its own right, with Scott’s original vocal delivery hinting at the style he would make his very own in the upcoming few years. The group consisted of his cousin Dominic on drums, Stan Getz (not the famous jazz musician) on bass, and Dave Rohillier on lead guitar. The fiddle player, Wayne “Arkansas” Sudden, came to the session but didn’t play. It is interesting to note that Stan Getz would also play on the other phenomenal Detroit rockabilly masterpiece “Long Blond Hair” b/w “Rock Rock” by Johnny Powers, revealing what a small rock and roll community Detroit had at the time.

The group took their acetate around to all the local record shops, trying to find a label that would release it. One record store man named Carl Thom played the dub for the local ABC-Paramount rack jobber, who then mailed the acetate to New York for the label bigwigs to hear. Like many other labels, ABC-Paramount was keen to get new rock and roll records on the market and leased quite a few regionally recorded tapes for release. They put out “Baby She’s Gone” b/w “You Can Bet Your Bottom Dollar” straight from Scott’s demo tape, not bothering to do a big studio recut of the tracks, in April 1957 as ABC-Paramount 45-9818. The record was a small local success, but not a hit, so ABC-Paramount tried again with a second release, “Two Timin’ Woman” b/w “I Need Your Love” (45-9860) in November 1957. Although “Two Timin’ Woman” was another classic rocker, this record sold even less than the first one and Scott was soon dropped from the label.

By early 1958 he had composed two new songs that he felt were hit material. He recorded acetate dubs of the new songs in order to pitch them to record labels. The rocker was a blast of a number about a friend he had who was always getting into trouble. The problem was that it was called “Greaseball,” surely an apt title but one that didn’t fly with record company executives, who felt it might insult the Mexican-American community. After the record company told him to change the title, Scott went into the studio bathroom and saw that someone had written “Leroy was here” on the wall, and he immediately changed the song title to “Leroy.” The flip side was another ballad, entitled “My True Love.” Legend has it that Scott wrote it for his first girlfriend. As ballads go, it was the first fully realized number that epitomized the Jack Scott ballad style: a near-dirge tempo with simple, teenage lyrics delivered in a plaintive, drawn-out drawl. This style became a favorite of greasers, teddy boys, and rockers around the globe. Scott would work this ballad style for years (check out the new companion collection to this one, entitled Jack Scott Ballads, for more of these slow grinders).

Although some have stated that “Leroy”/”My True Love” was issued first on the Detroit-based Brill label, this author has never seen a copy to verify its existence. Several Detroit-area record collectors vouch that there was no such release. It is possible that it may have been put out on another acetate dub record with the Brill label, which would explain the confusion.

What is known is that a song plugger from New York, Jack “Lucky” Carle (brother to Frankie Carle, the easy-listening musician), heard the record and took it to Murray Deutch in New York City, who was the general manager of Peer-Southern Music Publishing Company. Deutch contacted Joe Carlton, who purchased the two cuts along with an option on Jack Scott’s career for $4800 and soon released “Leroy”/”My True Love” on his own Carlton label in June 1958. Deutch snagged song publishing as his cut on the deal, and Joe “Lucky” Carle assumed a management role in Jack Scott’s career. Leroy became an immediate hit, and Scott was suddenly a rock and roll star, although he was still a kid living at home with his parents. After “Leroy” peaked at number twenty-five on the charts, the disc jockeys turned it over and began playing “My True Love,” which eventually peaked at number three and became one of the biggest hits of 1958.

Jack Scott had indeed arrived. Unfortunately, due to his multitiered management, publishing, and record label arrangement, he was also soon to learn all about the vagaries of the music business, and how everybody except the artist manages to get a big chunk of the money. He was twenty-two, though, and at the time was just happy to have a record that was played every morning on the radio in his mother’s kitchen.

Scott’s band had made some adjustments, too, bringing in the talented Al Allen on guitar and George Kazakas on saxophone. Scott also brought in a vocal backing group from across the border, a young group of Canadian singers called the Chantones. The Chantones were from Windsor, Ontario, Scott’s original hometown, and they added a unique sound to the Carlton recordings. Their name came from the French phrase nous chantons, which simply means “we sing.” Although their influences were strictly white-bread vocal groups such as the Crew Cuts and the Four Freshmen, their harmonies were somewhat ragged, not polished, and with a heavy accent on the bass singer. It was a unique sound, and the Chantones input on the classic Jack Scott rockers cannot be overemphasized.

Jack Scott had indeed arrived. Unfortunately, due to his multitiered management, publishing, and record label arrangement, he was also soon to learn all about the vagaries of the music business, and how everybody except the artist manages to get a big chunk of the money. He was twenty-two, though, and at the time was just happy to have a record that was played every morning on the radio in his mother’s kitchen.

After the success of “Leroy,” Scott was off and running. A series of excellent tracks followed, including “Geraldine,” “With Your Love,” “Save My Soul,” and another classic Jack Scott ballad entitled “Goodbye Baby” (included here), which rose all the way up to number eight on the charts. The next single, “I Never Felt Like This” b/w “Bella,” was another great effort that failed to chart, though it was a perfect distillation of all the right elements, with a cool Magnatone vibrato effect on Al Allen’s guitar, a memorable melody, and excellent mood backing vocals by the Chantones.

The next release, which only reached number thirty-five at the time, without question became the song that has defined Jack Scott ever since: the greaser classic “The Way I Walk,” backed with another good rocker entitled “Midgie.” “The Way I Walk” is perhaps the ultimate in greaser bravado, a song that means little to the casual listener but says volumes to the hipster who can relate to such lines as “The way I walk is just the way I walk.” Greaser existentialism at its finest, it was a language that could not be understood by the older generation but fully connected with the kids. Jack Scott had his own style—not a frantic, out-of-control way of rocking but instead something that bordered on a slow burn. It was menacing, but like a mean look or a slight gesture rather than a fist to the face. As those who have studied horror films or film noir know, sometimes these implied feelings are more compelling and hold more power than an explosion of violence. Jack Scott’s finest moments, such as “The Way I Walk,” are perfect examples of this.

Scott recorded several of his new Carlton singles in true stereo, which had just become commercially available in 1958. After Elvis Presley’s binaural stereo recordings of 1957 (which were not released until the 1980s), Jack Scott’s stereo recordings of 1958 and 1959 were the first stereo recordings to be released by a white rock and roll artist. The only downside to this achievement was that when the stereo version of his first album, simply titled Jack Scott (Carlton LP 12/107) was released, half of the album was remixed in rechanneled fake stereo, taking away from the fact that the other half was indeed breaking new ground.

Scott was drafted in January 1959 and immediately began applying for deferment based on the grounds that he was supporting his parents and siblings. That didn’t fly, so he applied for a medical discharge on the grounds of a chronic ulcer. The ulcer freed him from service, and he was out by May 1959.

A feud between Peer-Southern music publishing and Joe Carlton at Carlton Records resulted in Scott being wooed away from Carlton to record for a new American wing of the British label Top Rank. In retrospect, Scott wished he had remained with Joe Carlton, but it was a management decision and he went along with the party line. Scott was just beginning to learn that he was a product, being bought and sold by men in suits on the East Coast, each of them taking a piece of him and leaving Scott with lots of glory but no songwriting, publishing, or performance royalties. It was a classic, sad tale of the music business.

Top Rank entered the game with a fantastic two-sider, “Baby Baby” b/w “What in the World’s Come Over You,” which both sounded like a continuation of what Scott had been doing over at Carlton. “Baby Baby” was another great rocker in the “Leroy” tradition, but the ballad side, “What in the World’s Come Over You,” turned out to be the hit and ruled the airwaves in the first few months of 1960. It peaked at number five on the charts.

About this time, Joe Carlton exercised his right to release Jack Scott material. Carlton’s buyout stated that he could not release new singles, so Carlton put out a new album sneakily titled What Am I Living For to subliminally capitalize on the success of “What in the World’s Come Over You,” leasing the four 1957 sides from ABC-Paramount to round out the album as well as a number of singles on a new label he started, Guaranteed. As far as Scott’s career was concerned, it was terrible timing to have these other releases clogging up the marketplace when he was putting out new material on Top Rank. Of course, many years after the fact, fans were grateful that such rockers as “Go Wild Little Sadie” and others were released and not left in the vaults.

Really, Scott had little to complain about in 1960, however, as his next release on Top Rank, “Burning Bridges” b/w “Oh Little One,” became a number-three hit. “Burning Bridges” became the biggest-selling record of his career.

Top Rank released no less than three Jack Scott albums in less than a year and a half. What in the World’s Come Over You was a collection of his hit singles and cool album tracks such as “Good Deal, Lucille.” Strangely enough Top Rank released two specially recorded concept albums, I Remember Hank Williams (a collection of midtempo Hank Williams tributes with rather milquetoast production) and a gospel album called The Spirit Moves Me. The latter two are rarely discussed among the greasers that hold Jack Scott near and dear to their hearts.

Again the music business treated Scott like a pawn in a chess game. In 1961 Top Rank Records went out of business and Scott’s contract, along with all the old Top Rank masters, were sold to Capitol Records. Scott wanted to investigate other avenues, but the suits in charge of his career were making the decisions for him, which he ultimately regretted, especially the move to Capitol. Whereas the sessions for Carlton and Top Rank had been loose, informal, and creatively controlled by Scott himself, the Capitol sessions were formulaic productions where Scott walked in the studio to find already-finished backing tracks for songs he hadn’t written or chosen.

Scott was told time and time again by the people who owned him that these songs were the new “in” sounds, so Scott recorded whatever they put in front of him. The sad thing is that they took away the originality he had brought to the table with his own brand of Detroit rock and roll. The Capitol recordings are far inferior to those he did with ABC-Paramount, Carlton, and Top Rank, though a few good rockers and ballads escaped such as “Grizzly Bear,” included here.

More than anything else, the record business was literally changing around Jack Scott, rather than the other way around. To his credit, Scott never really changed his style to suit a new fad or craze—he was always just Jack Scott. When the Beatles took over in 1964, he did what a lot of previous rockers did and began recording pop-influenced country music that was essentially a continuation of what he’d been doing all along.

When his Capitol contract expired in 1963, Scott phoned RCA Records in Nashville and wound up with Chet Atkins himself on the phone. Atkins was coming up to Detroit to do a demonstration for Gretsch Guitars, and he asked Scott to pick him up at the airport and loan him a flattop acoustic guitar for the performance. Scott shuttled Atkins around Detroit and played him a few songs. The next morning, on the way back to the airport, Atkins asked Scott to record for RCA Records, or, more accurately, its Groove subsidiary.

Scott’s releases on Groove (and, beginning in 1965, RCA proper), starting with his first single in December 1963 all the way to his last in 1966, were eerily timed with the Beatles’ massive takeover of the music industry. That said, Scott kept plugging along, making good records that failed to click with the country music audience. He recorded a few very good 1950s-style rockers at RCA/Groove that must have seemed terribly out of place in the British Invasion marketplace, but today they are enjoyable, if slightly awkward, to listen to. Tracks like “Meo Myo’,” “Wiggle On Out,” and “Flakey John” are almost like a greaser’s last stand, but enjoyable in retrospect. Even Scott states that these records didn’t have any “balls” (his word), but for 1965 and 1966 they were great stabs at keeping real rock and roll alive.

Although to the greater record-buying public it must have seemed like Jack Scott was retired from the business after his RCA-Groove contract ended in 1966, he kept releasing singles that didn’t connect with the record buying public, first for ABC-Paramount, the label he’d started with in 1957, then Jubilee, then GRT, then one last major-label stand in 1973 and 1974 on Dot Records. These records were all good enough attempts at current country and pop, but there wasn’t a song in the bunch that was hit material, and by the mid-1970s Scott was back to playing the local bars around Detroit. He kept demoing new material, thinking the opportunity would arise for a new career, but he had no idea where that opportunity would come from. As it happened, it turned out to be Europe, where a new crop of greasers and teddy boys who had discovered Scott’s 1950s classics were clamoring for the man himself to come and make personal appearances and new records. Since then Scott has played local shows around Michigan as Jack Scott the local hero and toured over in Europe several times a year as Jack Scott, rock and roll legend.

This collection of Jack Scott rockers is the first of its kind, focusing on all of his great rocking numbers from 1957 until 1966. It’s only one side of Jack Scott, the artist, but the other side can be sampled on the companion volume, Jack Scott Ballads. If you just can’t get enough Jack Scott, the massive Bear Family box set remains an attractive option for the completist.

Jack Scott has secured a niche for himself in the history of rock and roll. As he likes to point out, he had more hits than Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran combined. His sound endures to the present day, loved by “greaseballs” the world over. We hope you enjoy this set, because Jack Scott does indeed ROCK!