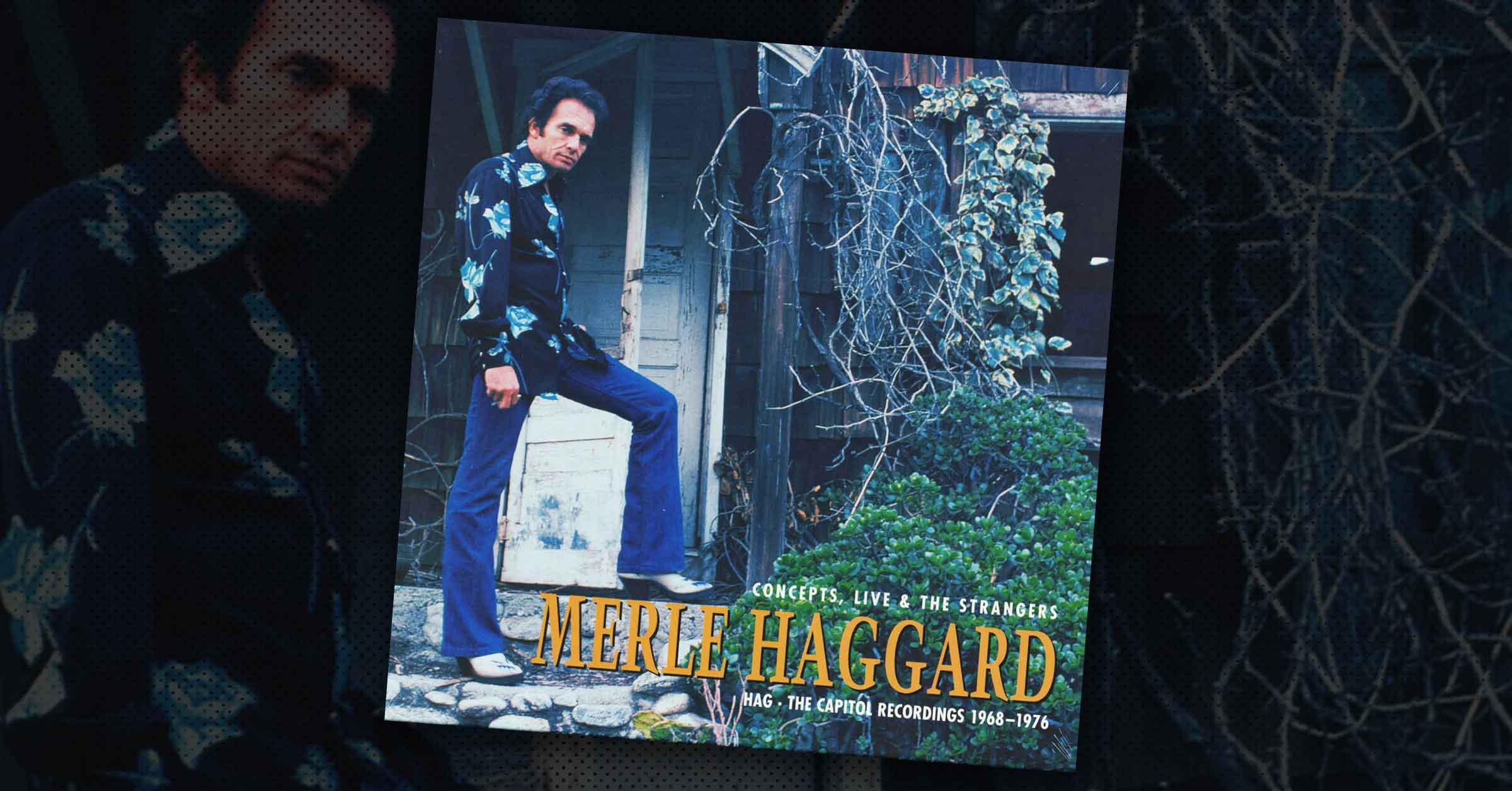

Liner notes for Hag: The Capitol Recordings 1968–1976 (Concepts, Live, and the Strangers), Bear Family Records

Originally published in 2007

One thing that cannot be said about Merle Haggard—the man has never been afraid to try something new. In a career that has spanned forty number-one hits, nearly a hundred albums, induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame, and just about every award imaginable, Merle has never seemed content to rest on his laurels.

Most of country music’s great artists are glorified one-trick ponies, making album after album of same-sounding material. In examining the recorded output of Merle Haggard, it becomes apparent that this was never the case for him. With an energy that bordered on the pathological, Merle Haggard seemed intent on doing it all.

Merle Haggard was the first country music star to realize that with great fame and fortune came great opportunities to realize his own personal dreams and ambitions. In today’s world, where rock stars’ whims are indulged as a matter of fact, this may not seem like such a revelation. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, Merle Haggard was bringing new rock-style sensibilities to the country music world.

Other stars had recorded tribute albums, or live albums, or gospel albums, of course. But whereas most stars would take half an afternoon to record their gospel album, Merle Haggard took the power that came with his newfound stardom and insisted that Capitol Records record four different live recording sessions at four different churches, and released a double live album of gospel field recordings worthy of inclusion in the Library of Congress.

Every special project that Merle Haggard took on during this time was this way—done with the ferocity of a man intent on proving something to the world. The Jimmie Rodgers tribute album was a double album recorded at the low point of Rodgers’s fame and visibility. The Bob Wills tribute album was put together with Wills’s help and advice, reuniting old members of the Texas Playboys. The live albums, all ambitious projects, were done on the road in Muskogee, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. Haggard’s excellent band, the Strangers, were allowed to record five albums of their own instrumentals and vocals.

This box set collects all the special projects that Merle Haggard and the Strangers tackled during his stay at Capitol Records. While some may view this third Haggard box set as an optional purchase, the truth is that to understand the artist known as Merle Haggard, this box set may in fact be the most essential. Beyond the massive hit singles and gold albums, this box shows Merle Haggard at his creative best, a man at the height of his powers.

SAME TRAIN, A DIFFERENT TIME

“Merle Haggard is the Jimmie Rodgers of our time.”

—Hugh Cherry, in the liner notes of Same Train, A Different Time

“When I was a boy, I guess those songs that Jimmie Rodgers sang about ridin’ them trains and seein’ those different places sort of inspired me. And when I got old enough to go, I went and caught me a train myself.”

—Merle Haggard to Dale Vinicur in the Untamed Hawk box set liner notes

The United States of America had changed radically in the six years since Merle Haggard had begun making records. By 1968, the Beatles had come in from England to become the biggest-selling music act in the world; the civil rights movement had changed the racial landscape of the country; the Vietnam War had torn the nation in half; and even the staid world of country music had changed radically, with new psychedelic sounds, go-go drum beats, and socially charged lyrics. Merle Haggard, coming off a streak of hit records, saw the timing as no problem to do a double-album tribute to one of his heroes, Jimmie Rodgers.

Jimmie Rodgers, a popular singer who died in 1933 of tuberculosis, was known as the Singing Brakeman and was one of the key figures in the commercial birth of country music. His recordings for RCA Victor were among the first successful country music records ever produced. The body of work that Rodgers left behind, from 1927 until his death in 1933, was hugely influential—singers from Gene Autry to Hank Snow to Ernest Tubb to Lefty Frizzell all got their start merely imitating Jimmie Rodgers to the best of their ability. When the Country Music Hall of Fame was established in 1961, Jimmie Rodgers was one of the first to be inducted.

And yet, by 1968, Jimmie Rodgers was a forgotten figure to the general public, a discarded curiosity, a Victrola-era anachronism. His influence had been absorbed and recycled so many times that few remembered it was Rodgers who had successfully brought the blues from Southern black culture into the folk melodies of white culture. Rodgers’s songs of a bygone era, with their subject matter of hobos and trains, were without a doubt as unhip as one could conceive in 1968.

Tributes to Jimmie Rodgers were certainly nothing new, even though Rodgers’s influence had waned considerably between the 1950s and 1960s. Two of Ernest Tubb’s first releases in the late 1930s were Rodgers tributes. Lefty Frizzell released a tribute album to Rodgers in 1951, and Hank Snow released another similar album in 1953. It was, in fact, the Frizzell tribute album, reissued in the late 1950s as a budget-priced repackage, which first exposed Merle Haggard to the music of Jimmie Rodgers.

Merle remembers: “Lefty introduced me to Jimmie Rodgers. Then, when I got all the Jimmie Rodgers stuff, I seen that Lefty hadn’t pumped the well dry, there was still a lot of stuff there. So, I thought that the job hadn’t been completed, that Lefty had started something that I’d finish.”

Merle had already recorded one of Rodgers’s songs, “My Rough And Rowdy Ways,” in August 1966, and as he was about to record a second, “California Blues,” in August 1968, he was approached by broadcast legend Hugh Cherry with the concept of recording a whole album tribute to Rodgers.

Cherry, a Kentucky native and Rodgers fan, had seen Rodgers live in person as a youth and was, at the time, living in California and working for Dick Clark Productions. Cherry talked Merle and producer Ken Nelson into the concept of a Jimmie Rodgers tribute album with spoken narratives that Cherry would write. The concept was received with enthusiasm by Merle, and surprisingly, met with approval from Ken Nelson as well.

Ken Nelson: “I liked the idea. Jimmie Rodgers was a big name artist!”

Nelson’s quote is revealing. Ken Nelson was born in 1911 and was a young adult when Jimmie Rodgers died. Undoubtedly, a younger producer would not have approved of the choice to do a Rodgers tribute in 1968 —it could very well have been career suicide for a hot young artist like Haggard —but Nelson, nearing sixty years old and out of touch with how much the market had changed, let the unlikely idea slip past the Capitol Records bean counters and go into production, as a double album, no less.

Merle: “There was a conversation that I heard about, between Ernest Tubb and another singer, and they were trying to get a dozen Jimmie Rodgers songs that they liked. And they couldn’t narrow it down to less than fifty. I heard about this conversation, and I said, you know, there’s some of these songs that I can do better than Lefty did, and some I know I can’t do as good, but I think there needs to be more than just eight or ten, I think there needs to be as many as I can do.”

Merle had learned that his father (who died when Merle was just nine years old) was a huge Jimmie Rodgers fan, and the fact that his hero Lefty Frizzell had recorded a tribute album cemented Rodgers’s lofty status in Merle’s mind. Never mind the fact that most artists would have been worried about their standing in the charts, jukebox plays, and units sold at this stage in their career. This was the first time that Merle Haggard’s unflinching artistic vision was revealed to the public —commercial viability be damned, Haggard was going to do what he wanted to, and what he wanted to do was a tribute album to Jimmie Rodgers.

While many had paid tribute to Jimmie Rodgers the singer over the years, few had recognized the genius of his songwriting ability within the fairly simple context of his twelve-bar blues and waltzes. Merle remembers seeing the songwriter credits on these records, written in tiny letters beneath the song titles, and realized that it took a great deal of living to come up with songs like these.

Merle, to author Charles K. Wolfe: “You know, Jimmie Rodgers rode freight trains and then wrote about it. And at a very early age, I did see the necessity to write your own songs.”

One of Merle Haggard’s great attributes as a performer is his believability. People believe Merle’s songs about prison because Merle spent time in prison. People believe Merle’s songs about riding trains because Merle actually rode trains. Merle recognized from Jimmie Rodgers’s songwriting that writing about things you know was an important element of believability. If there is one unifying thread between Rodgers and Haggard, it is this idea of having lived the songs that you sing, and the air of believability that both men exuded when they sang the songs they had written.

The recording of “Same Train, a Different Time” took place over seven recording sessions between August 1968 and March 1969. The sessions were an interesting mix of authentic acoustic performances and current sounds with electric guitars and drums. Somehow Haggard made the mixture of old and new successful, a feat that few, if any, of his peers could have accomplished.

“California Blues” (also known as “Blue Yodel #4”) was recorded as part of another session on August 26, 1968. The song had been revived by Webb Pierce and Lefty Frizzell in the early 1950s, but lay dormant and forgotten until Haggard recut it at this session some fifteen years later. The song was a natural choice for Haggard, with its lyrical content about the Okie migration to the West Coast. The results were deemed successful, and the plan for a full Rodgers tribute crept forward, as Merle carefully chose the songs he wanted to record.

The first dedicated session of Rodgers material was held on September 26, 1968, after the Strangers had spent the earlier part of the day recording several tracks for their first instrumental album. The group reconvened after a lunch break and recorded the first three Jimmie Rodgers songs for the album: “Train Whistle Blues,” “Travelin’ Blues,” and “Why Should I Be Lonely.”

It’s interesting to hear how Merle and the Strangers put these songs together. On “Train Whistle Blues” and “Travelin’ Blues,” Norm Hamlet plays an acoustic Dobro instead of the electric pedal steel guitar, certainly a hallmark of the old-timey sound, but drummer Eddie Burris plays a syncopated bass drum through the choruses, a staple of 1960s country. It shouldn’t work, especially with songs that dated from the 1920s, but it does.

On “Why Should I Be Lonely,” Hamlet is back on the electric pedal steel guitar, but session man James Burton plays his Mosrite Californian electric Dobro, an instrument he had taken to playing on many sessions that year (that’s Burton and the Mosrite Dobro on the intro of “Mama Tried”), and on the Rodgers material, it lends an authentic feel.

The next time Haggard came into the studio was November 5, 1968. Only two Rodgers numbers came from the session that day, “Peach Pickin’ Time Down in Georgia” and “Hobo’s Meditation.” “Peach Pickin’ Time” featured Roy Nichols and James Burton trading off some great solos, with Nichols playing an acoustic guitar very much in the style of Django Reinhardt, and Burton playing his Mosrite Dobro.

The next day was spent recording two non-Rodgers songs, but on November 7 the Jimmie Rodgers tribute resumed in earnest. In a short three hours the group recorded five songs: “Mother, the Queen of My Heart,” “My Carolina Sunshine Gal,” “Nobody Knows But Me,” “Blue Yodel #6,” and “No Hard Times.”

This session was the most traditional of all the Rodgers tribute sessions. Eddie Burris contributes a few 1960s-era drumbeats, but for the most part these songs were all done with acoustic instruments, very much in the style of Jimmie Rodgers’s original recordings.

There was another non-Rodgers session in December 1968 (which resulted in “Every Fool Has a Rainbow,” “Hungry Eyes,” and “Silver Wings”), but on January 22, 1969, Merle and the Strangers once again gathered at the Capitol Tower to work on the Jimmie Rodgers project.

This time around, the proceedings were not so reverential to the old-time sound. The first song done at this session, a reworking of the old murder ballad “Frankie and Johnny,” begins with a strummed acoustic guitar, as many of the other Rodgers songs do, but is interrupted by the classic biting treble of James Burton’s electric Fender Telecaster guitar, signaling that this was going to be different. Indeed it was, but with glorious results.

Merle: “You go listen to ‘Frankie And Johnny,’ you’ll hear two of the best guitarists in the world, Roy Nichols and James Burton, playing against each other, each one trying to outdo the other.”

James Burton: “I never tried to out-play another guitar player. When I play with other guitar players, I try to complement the other players, not compete.”

Also tackled that day were “Miss the Mississippi and You,” “Jimmie’s Texas Blues,” and the only song that was recorded but not released at the time, “Jimmie the Kid.” The latter would make its debut on Bear Family’s original CD reissue of Same Train, a Different Time but lay unreleased for more than two decades. (We have also included two more Jimmie Rodgers songs, “Mississippi Delta Blues” and “Gamblin’ Polka Dot Blues,” which were recorded in 1972 and released on the Roots of My Raising LP in 1976. Although they were recorded later, they fit right in with the rest of the Rodgers tribute material.)

Once again the group reassembled the next day in the studio to lay down another batch of Rodgers songs. Like the previous day, the arrangements were more contemporary than traditional, beginning with the old Rodgers classic “Waiting for a Train,” which was done with a style that emulated some of Haggard’s most recent hits.

“Down the Old Road to Home” was the lone song on the album done with just Merle’s voice and a single acoustic guitar. The spare arrangement only serves to highlight the lonesome feeling that the lyrics convey. Jimmie Rodgers’s “Last Blue Yodel (Women Make a Fool Out of Me)” has one of Roy Nichols’s wildest solos ever committed to tape, a flurry of notes on the acoustic guitar that illustrate his mighty prowess. “My Old Pal” is another one of Rodgers’s famous waltz ballads that Merle really sings his heart out on. The last song recorded on this day was “Hobo Bill’s Last Ride,” which Merle would record again on his “Live” in Muskogee concert album a few months later.

With all the tracks recorded up to this point, Merle had enough tracks to make his double album complete. However, a decision was made that the Rodgers tribute wouldn’t be complete without including a version of “Blue Yodel #8,” more commonly known as “Mule Skinner Blues,” and so on February 26, 1969, the group assembled to record the track.

“Mule Skinner Blues,” although it was not the best-selling Jimmie Rodgers record on release, would become the most recorded of all the Jimmie Rodgers songs, and the only one that would become a smash rock and roll hit, when the Fendermen covered it in 1960. The song has become a standard in bluegrass circles, from Bill Monroe’s famous arrangement, to the version Dolly Parton took to number three on the charts in 1970 (and re-recorded for her recent bluegrass album). After the Fendermen’s hit 1960 version of the song, countless rock and roll, rockabilly, and punk groups have revived “Mule Skinner Blues,” including most recently the Cramps.

Merle’s version of “Mule Skinner Blues” is faithful to Rodgers’s original, with some hot solos courtesy of James Burton on the acoustic guitar, Norm Hamlet on the acoustic Dobro, and Roy Nichols on the harmonica (Nichols plays harmonica throughout the Rodgers project).

On March 13, 1969, young hotshot producer and arranger David Gates (later to be the man behind the 1970s soft-rock group Bread) was enlisted to bring in a horn section of two trombones and three trumpets, who overdubbed Dixieland-style parts onto several of the songs, including “Travelin’ Blues,” “Nobody Knows but Me,” and “Jimmie’s Texas Blues.”

Hugh Cherry prepared a spoken-word narration for each song, but Ken Nelson convinced Cherry that any more than five narrations would be too many. Cherry also wrote the liner notes for the album, talking about both Rodgers’s enormous influence and Haggard’s place as Rodgers’s rightful successor. In the liner notes to the first reissue of Same Train, a Different Time, Cherry recounted to Charles K. Wolfe that Capitol Records would not pay his writer’s fee, and as a result Haggard paid him out of his pocket.

The double-album set Same Train, a Different Time was released on May 1, 1969, and thanks to Haggard’s huge stature at the time of its release, it shot to number one on the country album charts, and, surprisingly enough, number sixty-seven on the pop album charts. Almost right away, however, the album sank from the charts, due to a lack of promotion from the young people in Capitol’s promo department, a detail Merle is convinced was no accident.

Merle: “The record sold half a million records, and it sold the majority of it real quick. Maybe if the record had been on RCA Victor . . . because they owned Jimmie Rodgers’s publishing [actually, RCA owned Jimmie Rodgers’s recordings, and Peer owned his publishing, but Merle’s point still rings true]. . . . Let’s just say that Capitol wasn’t as Jimmie Rodgers-oriented as other labels might have been. I think RCA would have handled it better than anybody, because they knew who Jimmie Rodgers was.”

The fact of the matter was that while Merle, Ken Nelson, Hugh Cherry, and all the musicians might have thought that a Jimmie Rodgers tribute album released the same summer that America landed on the moon was a great idea, country record consumers weren’t quite on the same page. Although the public loved Merle Haggard, a double album of songs about hobos and trains was just too far out of the mainstream for true commercial success. The fact that an expensive double-LP sold so well on release was a testament to Haggard’s popularity, but not even Haggard’s immense popularity could bring it to the same sales level as “Mama Tried” or “Workin’ Man Blues.” Regardless, the album sold well enough over the years to remain in print, and has become a critics’ choice from the entire Haggard discography. It was the first time that a chart-topping country artist had dared to do something so commercially risky and artistically daring. Merle’s career wasn’t in jeopardy—he released no fewer than four albums in 1969, including the best-selling live album “Live” in Muskogee, and the combined hit-making juggernaut of his most recent number-one single hit “Okie from Muskogee” along with the hits he had scored in the previous five years. Those successes allowed Merle to take more risks like this one without fear of ending his career.

The fire had been started with the tribute to Jimmie Rodgers, but Rodgers had died in 1933. Merle Haggard then turned his attention to another one of his heroes, who was still alive: western swing legend Bob Wills. It was to prove another masterful move.

TRIBUTE TO THE BEST DAMN FIDDLE PLAYER IN THE WORLD (OR, MY SALUTE TO BOB WILLS)

Merle Haggard, in his own words: “Roy Nichols and I started listening to Bob Wills again in 1969. Bob’s career was as cold as he ever got in his life, about 1966 and through those years there, and I said one day to Roy Nichols, we were in my den, and messing around listening to old records, and I said, ‘Tell me something, are those old Bob Wills records as good as I remember ‘em to be?’

“Roy said to me, ‘Are you kiddin’? You damn right they are!’ So I said, ‘Well, let’s go get some, let’s go find some old 78 records.’ Roy knew that Bill Woods had a whole mess of ‘em, so we went over to Bill Woods’s house. Bill had a bunch of 78 records sitting around there, but he didn’t have a 78 player, nobody did, so I had to find me a 78 player. [In case you’re under thirty years old and have no clue what Merle is speaking of, the predominant form of recording before the early 1950s was the 78-rpm record, a ten-inch disc made of a breakable shellac/vinyl mixture that revolved at seventy-eight revolutions per minute on the turntable, unplayable on most modern turntables by the end of the 1960s.] I finally found a player, and I hooked it up to my good speakers, and put that Bob Wills record of ‘Brown Skinned Gal’ on the turntable, and it just knocked me and Roy Nichols right down on the floor! And I could not stand it, until I got me a fiddle.

“His music was wild, and it was different, and it was exciting, it was energetic. . . . Some of it really bad, and some of it really great. It was necessary for me to let people know how much I thought of Bob Wills.”

Bob Wills had been inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1968, which had probably triggered Merle and Roy Nichols into thinking about Wills’s music. Although Wills was one of the most popular entertainers in the Southwest from the 1930s through the 1950s, his popularity had waned considerably by the time he was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys formed in 1933 in Fort Worth, Texas, where Bob Wills and singer Tommy Duncan had previously been playing with the local group the Light Crust Doughboys. Wills’s brand of music was a mixture of hot jazz and fiddle tunes, a true integration of disparate musical styles that would come to be known as western swing. Influenced by blackface singer Emmett Miller, Wills developed a stage persona that involved whooping, hollering, cutting up, and joking. It was this minstrel-like persona of Bob’s that became the beloved part of the act, complementing the Playboys’ hot instrumental improvisations and Tommy Duncan’s boozy, good-natured vocals.

After moving from Fort Worth and setting up home base in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Wills and the Playboys began ruling the Southwest ballroom circuit, where they reigned supreme. Wills would eventually move his base to Fresno, and shortly thereafter, Sacramento, California, in the mid-1940s, where his popularity continued. In addition to their sellout dances, the group also made hundreds of recordings for Vocalion, Columbia, and MGM Records, not to mention an equally staggering number of radio transcriptions that were heard all over the country on the airwaves.

Merle Haggard: “People don’t understand how hot Bob Wills was out in California. They had several different shows every day that featured nothing but Bob Wills’s music. Eight o’clock in the morning until nine in the morning, you could go to KERN, a radio station in Bakersfield, and they’d play one hour of Bob Wills’s music. At eleven o’clock, you could go to a station in Delano, and from eleven til’ noon they’d play Bob Wills records. And if you were in the right place in America, at noon, he came on a noonday broadcast, live! Bob Wills was bigger than anybody. Out here in California, in our family and on the radio, he was hotter than anybody. Bob Wills, why if you’d have met him, it’d be better than meeting the president!”

Bob Wills was at the top of his game in the mid- to late 1940s, leading what many consider to be his finest lineup of the Playboys. As Merle’s testimony clearly shows, Wills’s popularity was unmatched among the refugees from Oklahoma and Texas that had fled to the central valley of California. From Los Angeles to Bakersfield to Sacramento, Wills’s brand of western swing held sway over country and rural audiences who flocked to his dances in record numbers.

Merle Haggard has his theories on Bob Wills’s popularity: “The secret . . . was his fiddle. He played the breakdown fiddle, he won a contest in 1932 in the streets of Fort Worth that paid a lot of money, and he won it in front of 7500 people. . . . He was voted the best fiddler. It was competitive, right off the bat, and his fiddle had power . . . to make men want to fight . . . dance . . . and make love. I mean, he had that in the power of his right arm. He could jump up there with that fiddle, and start wars! Or he could calm the sea!

“Roy Nichols said [Wills’s fiddle] was a weapon. He was right. You can take any show, and have the show dip a bit, and pick up the fiddle, and it’ll put it over the moon, every time. You can change the direction of the show, you can pick up the enthusiasm on stage, you can grab people’s attention. The minute you touch that fiddle, you’ve got everybody’s attention.

“Nobody ever stood up and played the fiddle until Bob Wills come along. . . . Everybody would sit down on the edge of a kitchen chair, don’t you see, and patted their foot, and stretched out like the Beverly Hillbillies [laughs]. Well, Bob got up out of the chair, and he was a dancer! He could dance, and he did blackface comedy, and he understood that he was entertainment. That was the difference with Bob Wills’s jazz over regular jazz.”

In his Sing Me Back Home autobiography, Haggard recounts another reason for his appreciation of Wills: “Bob Wills spent fifty years in the business I’ve come to love. He laid all the groundwork for country music today. He fought all the unions in the 1930s when country music wasn’t accepted at all unless the musician had a lead sheet and could do all the things some union official said a ‘musician’ ought to do. He was really the ramrod, the trail boss in the drive that has taken country music all over the world.”

Haggard’s devotion to Bob Wills music carried from his childhood to his formative years in music. Though Wills would gradually lose his popularity, first after firing his legendary vocalist Tommy Duncan in 1949, and later as the newer, louder, honky-tonk sound became the rage, Haggard remained unfazed in his devotion to Bob Wills and western swing music.

Another anecdote from Merle’s autobiography tells the story of Merle and his first wife, Leona Hobbs, going to see Tommy Duncan, the deposed Bob Wills vocalist, at a dance in rural Hanford, California, around 1955. Duncan’s fortunes had fallen rapidly since his dismissal from Wills’s band only six years earlier, and that night Duncan was performing to a handful of people in a hall that held nearly a thousand. Merle was invited to play guitar behind Duncan, in a ragtag band that included a dozen guitarists and mandolin players. The band was so bad that Duncan asked Haggard to move closest to him, complimenting his musicianship. After the show, Merle was distraught over one of his heroes being so broken down, which prompted Merle’s wife, who was known for such contrary outbursts, to remark, “Well, if the son of a bitch could sing, he could get a crowd.” The remark incensed Haggard so badly that a huge fight ensued, typical for his marriage to Leona Hobbs, but particularly harmful in the light of Haggard’s love for Bob Wills’s music.

Years later, when Haggard’s career took off to the highest levels of stardom, Bob Wills was still playing, but his health was failing and the crowds had fallen off to near extinction. Their paths crossed once in Nashville, around 1967 or 1968, when Wills and his touring companion and singer Tagg Lambert approached Haggard after taping an episode of the Kraft Music Hall at the old Ryman Auditorium. Wills slapped Haggard affectionately on the cheek, telling him, “We don’t pay much attention to the new music, but when your music comes on, we turn up the radio where we can hear it.”

A year or two later, by the time Merle and Roy Nichols sat around listening to old 78 records, joyously basking in their rediscovery of Wills’s music, Bob Wills was lying in a hospital bed in Fort Worth, a victim of several recent strokes. Merle decided that a tribute to Bob Wills would be a fitting follow-up to his Jimmie Rodgers tribute the year before. Haggard knew of Wills’s failing health and began planning the album in his mind. He knew he wanted to use some of the surviving Texas Playboys, and he also knew that he wanted to play the fiddle.

Merle: “I worked like a maniac on that fiddle, learnin’ how to play ‘Brown Skinned Gal.’ It was necessary for me to understand that it broke meter, and it went off in five different directions, and it had nothing to do with any music you’d ever played before.” Merle also told author Dale Vinicur for the Untamed Hawk box set, “I ended up practicing the fiddle eighteen hours a day. It became an obsession with me to learn to do it at least halfway right.”

Another reason, rarely mentioned, behind both Merle’s desire to play the fiddle and his obsession with doing a tribute album to Bob Wills was the fact that Merle’s father, who had died when Merle was only nine years old, played the fiddle and loved Bob Wills’s music. Learning the fiddle and doing the tribute to Wills thrilled Merle’s mother, Flossie Haggard, more than any other project Merle had ever undertaken.

Haggard also went to Fort Worth to visit Wills in the hospital. It was here that Wills advised Haggard which of the old musicians to use on his album. Eldon Shamblin, longtime Wills guitarist, told author Rich Kienzle for the Faded Love Bob Wills box set: “Haggard went to Bob, and asked him who to use, and Bob told him.” The Playboys selected to join Haggard and the Strangers for the project were Shamblin on guitar, Tiny Moore on mandolin, Johnny Gimble and Joe Holley on fiddles, Johnny Lee Wills on banjo, and Alex Brashear on trumpet. Wills himself could not leave his hospital room, preventing him from being on the album.

Johnny Gimble remembers meeting Haggard in Nashville shortly thereafter: “I was doing a recording session with Lefty Frizzell at Bradley’s studio, and during a break this head popped up, and it was Merle, who was hanging out watching Lefty record. Merle said to me, ‘Can you play ‘Brown Skinned Gal’? He kept talking about ‘Brown Skinned Gal,’ and how Bob broke meter on it when he played. Now, Bob Wills didn’t even know what meter was, if you had asked him, he’d probably have thought it was something you put nickels in when you park your car. Later on, I did a session with myself, Eldon Shamblin, Tiny Moore, and a girl singer named Laura Lee. The producer said to me later, ‘It’s amazing how you musicians all break meter . . . at the same time!’ [laughs] We were just playing the way we did with Bob.”

Haggard was furiously studying how to play Wills’s music in the latter part of 1969 and early 1970. During the recording of Fightin’ Side of Me—”Live” in Philadelphia, which took place in February 1970, Haggard and the Strangers took their first stab at a Wills arrangement, performing “Corrine, Corrina” with Hank Snow’s fiddle player, Chubby Wise, sitting in with the band. Merle: “I didn’t have a fiddle player in the band, at that time, and I couldn’t play fiddle, and I wanted to do ‘Corrina’ on that album . . . ‘cause that was such a favorite song of mine, since I was a child.”

Haggard was also introduced to minstrel singer Emmett Miller while visiting Wills in the hospital. On one of his visits to see Wills, Haggard heard music at a very low volume coming from underneath Wills’s hospital bed. When Haggard asked what the music was, Wills brought Haggard down close to his face, and whispered to him that it was Emmett Miller, “the best singer who ever lived.” Haggard eventually obtained a copy of the tape from Wills, made up of a collection of Emmett Miller’s 78 rpm records from the 1920s and 1930s, and would dedicate his 1973 I Love Dixie Blues…So I Recorded “Live” in New Orleans album to Emmett Miller, in addition to recording three songs Wills had learned from Miller. For the Wills tribute album, Haggard recorded “Right or Wrong,” one of the numbers that Wills had learned from Emmett Miller’s arrangement.

The recording of A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (Or, My Salute to Bob Wills) took place over three days in April 1970. Merle Haggard and the Strangers met up with the six former Texas Playboys—Johnny Gimble, Joe Holley, Tiny Moore, Eldon Shamblin, Johnny Lee Wills, and Alex Brashear—and augmented themselves with champion hoedown fiddler Gordon Terry. The various Playboys came in from their far-flung locales to reunite at the Capitol Tower in Hollywood, and without any rehearsal whatsoever, the assembled congregation got down to the business of recording as many tunes as they could in the time they had available.

Haggard’s band had been rehearsing the tunes in anticipation of sitting down with the veteran musicians, and it must be said that for a group made up of young men who had recently topped the country charts with such hard-edged fare as “Workin’ Man Blues” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” the Strangers succeeded admirably in nailing the essence of the western swing sound of the 1930s and 1940s.

The first day of recording, April 6, 1970, also happened to be Merle Haggard’s thirty-fourth birthday. It is easy to imagine the joy it gave Haggard to gather around his heroes, playing fiddle alongside masters of the instrument like Johnny Gimble, Joe Holley, and Gordon Terry. The first song that the assemblage of musicians tackled was the old standard “Right or Wrong,” one of the most popular numbers Wills had ever recorded, and a staple of the Bob Wills show for decades. The results were great; the melding of the seasoned Wills alumni and young Strangers a success on all counts.

Haggard then tackled the number that had tickled his fancy so much the year before, “Brown Skinned Gal.” The difficult fiddle piece was used as an introduction for the LP, with a spoken-word bit overdubbed on top of the instrumental track. Although it was only fifty-one seconds long, Haggard had succeeded in learning how to play “Brown Skinned Gal” well enough to record it.

The Strangers were allowed to shine on the next track, a rollicking remake of the classic “Roly Poly.” Roy Nichols takes one of the best jazzy solos of his career, and Norm Hamlet takes a great solo in the non-pedal steel style, showing his understanding of the proceedings (Hamlet had become one of the modern masters of the pedal steel style, but had started his career listening to non-pedal players like Vance Terry and Joaquin Murphy).

“Corrine, Corrina,” the tune that Merle and the Strangers had recorded earlier in the year for the live Philadelphia recording, becomes a showcase for the Playboy alumni, who each take frighteningly great solos. Compared to the rather anemic version on the Philadelphia recording (the band came in too slow because of guest fiddler Chubby Wise counting off wrong), this version positively cooks.

After a break for lunch, the group reassembled and laid down a great ballad, “I Knew the Moment I Lost You,” a Bob Wills and Tommy Duncan collaboration from 1941. Merle handles the delivery with his typical aplomb, giving it a more soulful delivery than Tommy Duncan ever had.

The last song tackled on the first day of recording was a great version of the old blues number “Trouble in Mind.” Why this number didn’t make it on the original LP issue is a mystery, as the performances are superb all around, from Merle’s bluesy vocals to the solos (again, another masterful solo from Roy Nichols). This version was eventually released (as was the other unreleased number from the Wills tribute sessions, “Spanish Two-Step”), as a bonus track for the CD reissue of the Hag / Someday We’ll Look Back albums.

The group came back the next morning, still on a roll from the day before, and lit into Tommy Duncan’s immortal standard “Time Changes Everything.” The fiddles of Gimble, Holley, and Gordon Terry were right on the money, some of the best men in the business effortlessly doing what few have been able to touch in years since.

No Bob Wills tribute would be complete without a version of “San Antonio Rose,” perhaps the best-known Wills song of all, and Haggard and the band didn’t chance leaving it off the album. Strangely enough, this recording is probably the least impassioned song on the album, a rather robotic read-through instead of the swinging romp it could be. Perhaps the Playboys alumni were just plain sick of doing the song. Perhaps they just wanted to break for lunch (“San Antonio Rose” was the last number they recorded before the lunch break). We’ll never know the real reason, but the version of “San Antonio Rose” found here is the only real disappointment on an otherwise flawless album.

When the band returned from their lunch break, another classic blues from the Wills oeuvre was committed to tape, “Brain Cloudy Blues,” essentially a rewrite of “Milk Cow Blues” with slightly different lyrics. This recording has an exceptional three-part harmony blues solo with Eldon Shamblin, Tiny Moore, and Roy Nichols seamlessly blending together.

With several blues and swing numbers in the can, it was fiddle time, and “Take Me Back to Tulsa” was a real barn burner, with some phenomenal fiddling courtesy of Johnny Gimble and Joe Holley and one of Tiny Moore’s hottest mandolin solos ever caught on tape.

It’s hard to imagine why the version of “Spanish Two-Step” recorded this day, with its flawless twin fiddle intro and hot solos courtesy of Roy Nichols and Norm Hamlet, wasn’t released on the original LP issue (like “Trouble in Mind,” it would lay dormant until both tracks were used as bonus tracks on the Hag / Someday We’ll Look Back CD reissue). The second day of recording ended with a swinging version of “Old Fashioned Love in My Heart.” Merle gives the tune a haunting vocal performance over the memorable minor-key chord changes.

The third day of recording was only a three-hour session, but that’s all Haggard and the band needed to finish the album. Another one of Wills’s most popular numbers was tackled first, “Stay a Little Longer,” and the band really cooks. Tiny Moore and Roy Nichols come in together with a twin harmony solo that should be listened to several times in a row to appreciate the amazing proficiency of their musicianship. The notes are so precise, and yet so freely swinging, that it’s easy to let the brief moment pass without realizing how great these musicians really were.

The last track recorded for the Bob Wills tribute LP was the classic “Misery,” a number written by Wills, Tommy Duncan, and Tiny Moore in 1947. A fitting end to the proceedings, “Misery” had all the classic elements that made Wills’s music so popular and beloved—a lonesome feeling created by the mournful twin fiddles and steel guitar chimes, and lyrics of a long lost love that have the ability to make grown men cry. Similar in feeling and lyrical content to the classic “Faded Love,” it was a successful end to a three-day recording project that no one knew would turn out so triumphantly.

Merle wrote in the liner notes to the Bob Wills tribute LP, “Never in my life have I enjoyed three days so much. I believe the enjoyment was shared by everyone involved because when the last note was played on the last song, which was an old tune called ‘Misery,’ a tear could be seen in almost any eye you chose to look at and mine was no exception.”

A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (Or, My Salute to Bob Wills) was released in November 1970, and almost single-handedly brought about the modern western swing revival. Haggard was so hot after his Muskogee and Philadelphia live albums, the Bob Wills tribute LP sailed to number two on the country charts and, incredibly, number fifty-eight on the pop charts. The album exposed the name and music of Bob Wills to an enormous audience of younger fans who had never heard of him before.

Two such listeners were college students Ray Benson and “Lucky” Oceans, a pair of young East Coast counterculture hippie types who became enamored with Haggard’s tribute to Bob Wills. The pair formed a group called Asleep at the Wheel, which continues today as perhaps the greatest exponent of Bob Wills’s music and western swing in general across the globe.

To Merle’s credit, the Bob Wills tribute album was not a “quickie” project. It was to have a lifelong impact on him and his career. Most significantly, Haggard would use Eldon Shamblin, Johnny Gimble, and Tiny Moore extensively over the years, both on record and on the road.

Merle: “We became friends, and I used ‘em on my records, John Gimble especially, and then Eldon . . . and then we got Tiny. And they were such great players that once you knew about ‘em, you couldn’t forget about ‘em. You had to include them in the circle of consideration when you went into the studio, you’d say ‘who are we gonna use on guitar?’ and then you’d say, ‘Besides Eldon?’ [laughs] It was a great lesson in music. These guys have given me a professor’s degree in music. I can go in with the finest musicians in the world, Jay Leno’s band, or Dave Letterman’s band, and communicate with them, because they respect me as a musician! And it’s because of the association I had with those great players and the things that I learned from them.”

In addition, Haggard kept in constant contact with Bob Wills during the last years of his life. In September 1971 Haggard arranged for Wills to come and visit him at his ranch in Bakersfield. Without revealing that Wills was going to be there, Haggard also invited a large group of surviving Texas Playboys to the ranch, mostly for a grand reunion, but also to make a recording for Capitol Records.

The men who had recorded the tribute LP were all there—Johnny Gimble, Eldon Shamblin, Tiny Moore, Alex Brashear, Joe Holley, and Johnny Lee Wills—as well as several other key members from Wills’s golden era. “Smokey” Dacus on drums, Leon McAuliffe on steel guitar, Al Stricklin on piano, and Bob’s brother Luke Wills on bass were all there as well as Tommy Duncan’s brother Glynn handling the vocal duties (Tommy Duncan died in 1967).

Al Stricklin to Wills’s biographer Charles Townsend: “If it had not been for Merle, some of us would never have seen each other again. I had not seen some of the boys in thirty years. The last time I saw Alex Brashear, his mustache was brown. Now he’s gray.”

When all the Playboys arrived, they were astounded to find their old boss waiting for them. When the band set up and started playing, several commented that just having the man present made them play better. Wills, who had remained in bed since his arrival at Haggard’s ranch, had his wife Betty dress him in his white hat and cowboy boots, and was taken in a wheelchair to the pool area, where the men were recording. Bob asked Betty to get his fiddle. Even though his right hand was paralyzed and he couldn’t play anymore, Bob Wills sat in front of the band, holding his fiddle and leading the band from the sheer force of his presence.

Ken Nelson brought Capitol Records’ remote recording truck to Merle’s ranch, and the band recorded nearly twenty tracks. Haggard suggested they kick off with “Osage Stomp,” a number that Wills had recorded at his first session in 1935, and from there the band ran through many of the staples of Wills’s repertoire, including “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” “Twin Guitar Special,” “Faded Love,” “Steel Guitar Rag,” “Misery,” and “I Never Knew,” ending with the classic “Sugar Moon.”

According to Charles Townsend’s biography of Wills, Haggard went to Wills and asked him, “Bob, how does it sound?” Wills remarked, “It lacks only one thing.” “What’s that?” “Me.” The music still burned inside Wills’s body, but his body had failed him.

The music recorded at Haggard’s ranch that day in 1971 remained unreleased for decades. Fans were told it wasn’t technically up to snuff, among other reasons, but in all honesty this was a project that Haggard did for himself. The results eventually came out on the Bob Wills Faded Love box set (Bear Family BCD 16550), which revealed that the reunion was a good, if not perfect, document of the historic event. Wills would eventually give Merle Haggard one of his prized fiddles, a grand gesture for the newly renewed interest that Haggard had gotten for him. Wills had been nearly forgotten a few years earlier, but now was basking in glory, receiving honors on top of accolades for the last two years of his life.

Haggard was also scheduled to appear on a recording in Dallas in December 1973. Another reunion of the Playboys had been brought together, for a more proper recording session, with Wills once again leading from his wheelchair. Unfortunately, Wills was only present the first day of recording, and Haggard was caught in a snowstorm driving down from Chicago to Texas. That night, December 3, 1973, Wills had a major stroke and never regained consciousness. The band continued to record for the next two days, including Haggard on fiddle but sans Wills, and the results were put together in a set called Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys—For the Last Time.

Wills passed away on May 13, 1975, after nearly eighteen months in a coma. Thankfully, the last few good years he had were full of remembrance for the music he had given the world. Without a doubt, if it hadn’t been for Merle Haggard’s album A Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World (Or, My Salute to Bob Wills), Wills might have died without knowing how much the world truly loved him and his music.

Merle Haggard had now paid tribute to two of his biggest inspirations, Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills. Though Haggard would eventually make more tribute albums to Lefty Frizzell, Hank Williams, and Elvis Presley, these first two musical tributes, both risky moves in light of their commercial viability, cemented Haggard’s reputation as a historian and visionary. Here was an artist not afraid to take risks for what he believed in, to put his money where his mouth was, to show the world what he thought was important, regardless of how many units were sold. It was the sort of thing that absolutely none of Haggard’s peers had the cojones to do, at least until Haggard blazed the trail and showed how it could be done.

THE LIVE ALBUMS

The live album is a tradition in country music. There is something about country music that demands “realness,” and there is nothing more real than an album recorded in front of a live audience.

The tradition of hearing country music in a live-audience setting dates back to the Grand Ole Opry and its many local variants across the country, such as the National Barn Dance in Chicago, the Old Dominion Barn Dance in Richmond, Virginia, and hundreds of other weekly radio shows that featured country music stars performing live in front of an appreciative audience.

Across the nation, people became accustomed to hearing country music stars interact with their audiences, telling them jokes, introducing the songs, and in turn hearing the audience going wild when the band reached a fever pitch. All of these factors helped influence the live recording as a venerated country music show business tradition.

The first live country music record was probably the RCA Country and Western Caravan album from 1954, which was a live recording of a touring road show that featured Hank Snow, Chet Atkins, Charlene Arthur, and others. It was released both as a dual-EP 45-rpm set and on the new LP long-playing 10-inch album format (reissued by Bear Family as a 12-inch LP in the 1980s, now out of print). The liner notes of the original release go into great detail about this album being the first of its kind, which may or may not be true, but what is true is that the album did not sell well and is a collectible rarity today.

The live album genre really got rolling, however, when Hank Thompson released his successful and highly influential Live at the Golden Nugget album in 1960. The album featured Thompson and his big western swing band in front of an appreciative audience, interspersed with sound effects of a Las Vegas casino (the album begins with the sound of a roulette wheel). Thompson would go on to make several more live albums, including ones from the Texas State Fair and Cheyenne Frontier Days in Wyoming, but it is the Live at the Golden Nugget album that is most remembered today.

One artist who was inspired by the Hank Thompson records was Johnny Cash, who saw the possibilities that the live album offered. When Johnny Cash released his Live at Folsom Prison album in 1968, the exciting, electrifying recording touched a nerve with the public, and the disc shot up to the top of the charts, a previously unheard-of achievement for a live recording. When Cash followed the next year with the even more successful Live at San Quentin, live albums were no longer seen as a novelty; they were a must in any country music performer’s catalog. The late 1960s and early 1970s then became the golden era of live country music recording.

Merle Haggard was a friend of Johnny Cash, and had even revealed his prison record to the public while appearing on Johnny Cash’s television show. Merle relates that the success of the Johnny Cash Live at Folsom Prison played no small part in influencing him to do a live album of his own.

OKIE FROM MUSKOGEE—”LIVE” IN MUSKOGEE, OKLAHOMA

Merle Haggard began playing his new song “Okie from Muskogee” even before the single was released in September 1969. By all accounts, they knew it was a smash hit just from the audience’s reaction to the not-yet-released song. According to steel guitarist Norm Hamlet, “The first time we played it, the audience just went crazy. We knew it was going to be huge.”

The audience’s reaction to the song inspired Merle and his manager, Fuzzy Owen, to concoct a somewhat harebrained scheme that resulted in one of the great live country music albums, Okie From Muskogee—Recorded “Live” in Muskogee, Oklahoma. However, some background information is required to understand how the album came to be.

Although he is barely mentioned in most history books, Charles “Fuzzy” Owen was every bit as important to the history of Bakersfield country music as his much better-known peers Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. Fuzzy Owen, no relation to Buck, hailed from Arkansas and even today the years have not softened the Arkie lilt to his accent. After moving to Bakersfield in the late 1940s, leaving to go into the army and returning around 1952, Fuzzy began playing steel guitar and singing in local bands. Fuzzy was by all accounts a talented steel guitarist and a good vocalist, but his greatest talent would come to be as a manager, recording studio engineer, record label owner, spiritual advisor, and tireless promoter of country music around Bakersfield. He is credited with starting the career of Merle Haggard, and indeed has been Merle’s manager and mentor from the beginning until the present day.

Fuzzy Owen had accumulated years of experience in the recording studio, having run the tiny Tally record label and recording studio in Bakersfield, where Merle Haggard made his first singles before signing to Capitol Records. When Merle began recording for Capitol, Fuzzy received credit as a coproducer on all his albums, but his involvement was mostly as an idea man and sounding board for Merle’s arranging and recording process.

When “Okie from Muskogee” hit, Merle and Fuzzy discussed the idea of doing a live album. The song was receiving a tremendous crowd response when Merle performed it, and it seemed like a natural idea. What followed next was hardly regular procedure, but it was something for the history books.

“One day I was sittin’ at home, and I got a phone call from Lewis Talley,” recalls Red Simpson, the truckin’ music singer and songwriter who was an old friend of Merle and Fuzzy from the early days of Tally Records. “He said, ‘Come on, we need you to help me drive a van full of recording equipment on tour with Merle.’ I said okay, and I went out to the van. It only had one seat, for the driver! So I asked Louie to stop at a market, and I bought a lawn chair, and rode in that folding lawn chair the whole way.”

Fuzzy and Merle had concocted a scheme where they would record Merle’s concerts, unbeknownst to Capitol Records, and submit the tapes as a live album for his next release. This sort of thing just wasn’t done, but with Merle’s stardom at its apex, they felt they could get away with it. As with many of the ideas cooked up by Fuzzy and Merle, it was a great idea and the time was right, and despite some comical difficulties in the execution of the idea, they wound up looking like geniuses at the end of the day.

Merle Haggard: “We were trying to cut an album called Six Nights on the Road, but that didn’t happen. As it turns out, we didn’t get anything until the last show of the tour, in Muskogee, Oklahoma.”

Fuzzy Owen: “This company sold me an 8-track Ampex machine, and the salesman lied to me, he told me that it had microphone preamps built into it. It didn’t, but we didn’t find that out until we were already on the road with the machine inside our van.”

Fuzzy had experience with the earlier tube models of Ampex recorders, the 300 and 350 series, into which you could plug a microphone directly. The machine he had purchased, the finest you could buy at the time, was an 8-track Ampex 440, the first commercially available 8-track recorder (though Les Paul had an experimental model as early as 1953). The new design left out the built-in microphone preamplifiers the earlier models had, but Fuzzy didn’t know that until their van was rolling down the road, with Red Simpson riding in a lawn chair, following Merle’s tour bus.

Fuzzy Owen: “What I did was stop at every little music store along the tour, and I was buying these little Shure microphone mixers, one at a time, until I finally had enough of ‘em to fill up the eight tracks. Each of the little mixers had four inputs on ‘em, so I could get several mikes going on each track. It wasn’t until Beaumont, Texas, right at the last part of the tour, that I finally found the last two Shure mixers to fill up the 8 tracks. But as it turned out, I didn’t really get everything working right until the very last show of the tour, in Muskogee.

“I remember we were playing at a prison down in Huntsville, Alabama, and I had all my wires set up to record, and the stage starts turning! No one had told me it was a revolving stage. So I had to stop the show, and I ran up there and grabbed all my wires and unplugged them. We had all sorts of problems on this tour getting that recording right. We had two overhead mikes, and about five RCA BK-5 ribbon mikes (a high-end microphone RCA made mostly for television sound), two microphones on the crowd, and the bass went in direct to the mixer. It was a disaster, really, until that last night, and everything just kind of came together.”

The album captures all the excitement that a live recording can deliver, with the Strangers playing like the well-oiled touring road machine that they were. While the recording has its technical limitations, the rawness of it all only adds to the excitement.

Merle remembers more detail: “We didn’t even have speakers to know if we were going onto the tape. All we had was Fuzzy saying, ‘Well, the meters say we’ve got a good recording, but we won’t know until we get some speakers to play it back on.’ So we were really lucky to get what we did. Fuzzy told me that night in Muskogee, he said, ‘If you’ve got this on tape, I’m not sure whether we did or not, Hag, but if you did, it’s a million seller.’ He said, ‘It’s great.’”

The album kicks off with an introduction by Carlton Haney, who at the time was the biggest country music promoter in the country. From his North Carolina base, he booked every major country act at one time or another. Haney is generally credited with being the first promoter to take country shows out of small clubs and put them into halls and arenas, and he holds the distinction of putting together the first large-scale bluegrass festival, virtually saving the genre from extinction. While many in the business, including Merle Haggard, would have money disputes with Haney and ultimately quit working with him, at the time of the Okie from Muskogee album, he was the P. T. Barnum of the country music world.

The band kicks off with Merle’s big hit “Mama Tried,” and from that moment on the audience is in the palm of his hand. The liner notes to the album state that the town of Muskogee, Oklahoma, was home to 38,059 citizens, and from the sound of it, they were all there in attendance that night. As the liner notes state, “The applause was like thunder.”

The first side of the album was dedicated to the hits. In rapid-fire succession, nearly all of Merle’s big hits up to that time were performed: “Mama Tried,” “Silver Wings,” a medley that included “Swinging Doors,” “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive,” “Sing Me Back Home,” and “Branded Man,” closing the A-side of the LP with “Workin’ Man Blues”. Another spoken word bit finds Merle receiving the key to the city of Muskogee. Interspersed between the hits, Merle performed Jimmie Rodgers’s “No Hard Times” (which he had recorded recently for his Jimmie Rodgers tribute album, Same Train, a Different Time) and Merle’s bass player at the time, Gene Price, performed “In the Arms of Love,” a song he cowrote with Buck Owens.

The B-side of the LP was dedicated to the mythological “Hobo Bill” and begins with a spoken-word “Introduction to Hobo Bill” by Merle. The band then launches into another tune from the Jimmie Rodgers songbook, “Hobo Bill’s Last Ride,” a standard that has been performed by everybody from Rodgers to Hank Snow to Grandpa Jones to Haggard (again, recorded shortly before this live recording on Merle’s tribute album to Rodgers, Same Train, a Different Time).

Merle introduces the next song, “Billy Overcame His Size,” as one he had just written. A fairly maudlin song about an underdog who dies trying to save the lives of others, it was perfect fare for the small-town family audience in Muskogee. Two more of Merle’s originals follow, “If I Had Left It Up to You” and the classic trucker ode “White Line Fever.” Although an unreleased studio version of “White Line Fever” had been recorded (and is included on the Merle Haggard 1969–76 Workin’ Man Blues box set, BCD 16749), it is this live version that has been copied over and over again by such disparate artists as Dave Dudley, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and even the English postpunk group the Fall.

The Strangers then let loose with an original instrumental, “Blue Rock,” which showcases the incredible abilities of guitarist Roy Nichols. The Strangers would rerecord the song four months later for their second solo LP, Introducing My Friends—The Strangers, with a completely different rhythm section, newcomers Bobby Wayne, Dennis Hromek, and Biff Adam replacing the lineup on this album that included Gene Price on bass and Eddie Burris on drums (and an uncredited Red Simpson on acoustic rhythm guitar—he can be seen in the tiny photo on the back of the album but is not mentioned by Merle during the band introductions).

The album ends with the title track, “Okie from Muskogee.” While the song had incensed liberals across the nation, playing the song for the citizens of Muskogee, Oklahoma, was like shooting fish in a barrel. Wild cheers erupt when Merle introduces the song and comments that Muskogee is “hippie free,” and during politically charged lines of the song such as, “We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street.” It sharply illuminated the fact that while people in the big cities had doubts about the Vietnam War and the political climate of the day, the rest of the country (which President Nixon described at the time as “the silent majority”), including towns in the heartland such as Muskogee, were still highly conservative and hated the new radical left-wing element.

Merle, for his part, has gone through a learning process over the years, coming to grips with his own opinions of the song (for a more in-depth examination of the “Okie from Muskogee” phenomenon, see the booklet to the Workin’ Man Blues box set, BCD 16749). When Merle performs the song now, he plays it off like a joke, and he has said in interviews over the years that it was a parody, or written from the perspective of his father. In a recent interview with this author, however, Merle admitted that when he wrote the song, he was angry with the antiwar movement. As an ex-convict, he felt that hippies and left-wing radicals were demeaning the fabric of the country, a country that had given him a second chance and forgiven him of his earlier crimes. He insists that he was dead serious when he wrote “Okie” and other politically charged numbers like “The Fightin’ Side of Me.” But as time went on Merle began to take a more educated and unbiased look at his own political views and personal beliefs. He discovered his own love of marijuana, claiming in a 1974 interview, “Muskogee is the only place I don’t smoke it,” and both he and the nation went through the impeachment of President Nixon, the failure of the Vietnam War and the fall of Saigon, and other revelations that the government had been lying to the public all along. “Okie from Muskogee” would always be one of his big hit songs, if not the biggest, and Merle knew that he would have to perform the song until the day he died. But when he performs the song now, the line “We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee, we don’t take our trips on LSD” elicits laughter from both Merle and the audience, a far cry from the angry conservative cheers of 1969.

There was no doubting the song’s appeal, however. As the liner notes to “Live” in Muskogee state, Merle had to sing the song over again that night, and indeed, on all three of his live concert albums, Merle would include a live version of “Okie from Muskogee.”

Returning to California, Fuzzy Owen mixed the tapes they had recorded in Muskogee. Merle recalls that Fuzzy handed a finished master over to Capitol’s Ken Nelson, announcing to Nelson, “Here’s your next album!” Nelson may not have been thrilled that they had gone behind his back, but he agreed to listen to the tapes, and when he heard them, technical deficiencies aside, he had to agree that the results were exciting.

Okie from Muskogee—Recorded “Live” in Muskogee, Oklahoma, was released in December 1969 and became a well-deserved number one on the country charts and a surprising number forty-six on the pop charts, a certified smash. It was voted album of the year by the Academy of Country Music (the single of “Okie from Muskogee” was voted single of the year). It would go on to become one of the top-selling country music albums of all time.

THE FIGHTIN’ SIDE OF ME—“LIVE” IN PHILADELPHIA

Merle: “We knew that live albums were the ticket for us, at the time. . . . They were selling so well that a blind man could have seen it was the thing to do.”

Fuzzy Owen, Merle’s manager, has a stoic view of Merle’s career that is much more matter-of-fact than most. He’s entitled to whatever he thinks, having managed one of the most successful country music singers of all time. The way Fuzzy sees it, Merle’s career has been a series of groups of successes: “We had the drinkin’ songs, we had the prison songs . . . and then we had the live albums.” It was really that simple, and the decision was made to follow up the highly successful “Live” in Muskogee album immediately—with another live album.

Following the success of the anti-hippie, conservative, right-wing message that had begun with “Okie from Muskogee,” Merle was riding high on the charts with his follow-up single, “The Fightin’ Side of Me.” While much of the country may have heard “The Fightin’ Side of Me” as a meaner, more visceral call to the far right—if not an outright declaration of open season on hippie-beating—Ken Nelson at Capitol Records thought Haggard’s new vision was “patriotic.” As such, the location of the next live album was Philadelphia, chosen, as the album cover itself states, for being “the cradle of American liberty.”

This time around, there would be no hillbilly hijinks; Red Simpson would not be riding on a folding lawn chair in a makeshift recording van. Ken Nelson enlisted Capitol Records engineer Hugh Davies (who had been engineering Haggard at the Capitol Tower since he signed with the label) to run the live recording rig. The show took place at Philadelphia Civic Center Hall as part of a radio station WEEZ Country Shindig. There was a huge crowd in attendance, approximately ten thousand people, one of the largest crowds they had ever played to at that time.

The Strangers had, in the short time between October 1969 and February 1970, made major changes in their lineup. Only Roy Nichols and Norm Hamlet remained from the previous band. Over the years 1968 and 1969, the band had fluctuated, with many session musicians brought in for the recordings and short-lived members brought in for live shows and tours. In early 1970 three musicians were brought in, all of whom had spent time as members of the house band at the popular country bar the Palomino in North Hollywood, California. With the addition of “Bobby Wayne” Edrington on auxiliary guitar, Dennis Hromek on bass, and Biff Adam on drums, the Strangers would remain virtually unchanged for the next four years (an eternity in the Haggard organization).

This new lineup had already gone into the studio in early February 1970 to record the majority of the second Strangers solo album, Introducing My Friends . . . The Strangers. Nonetheless, they had been playing together less than six weeks when they went to Philadelphia on February 14, 1970, to cut The Fightin’ Side of Me album.

Despite the new lineup of the group, and the presence of Capitol Records engineers and sound crew, the Philadelphia recording was very much a repeat of “Live” in Muskogee. Beginning with the introduction by promoter Carlton Haney, who did the intro on “Live” in Muskogee, the Philadelphia album sounds almost like a continuation of the previous album.

The Strangers kick off with Norm Hamlet’s steel guitar introduction, “Hammin’ It Up,” and then launch into Merle’s “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am,” followed by a take on Bob Wills’s arrangement of “Corrine Corrina” (which was probably a warmup for the Strangers, who would be in the studio less than two months later to record Merle’s Bob Wills tribute LP).

Hank Snow opened the show for Merle on this night, and for Corrina Merle calls up Snow’s fiddle player, Chubby Wise (one of the great bluegrass fiddlers, who was an original member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys in the 1940s and a mainstay of Hank Snow’s band for nearly two decades after his stint with Monroe). Merle remembers a humorous detail: “Hank Snow was on the show that day, and I didn’t have a fiddle player in the band at that time, and I couldn’t play fiddle yet, and I wanted to do ‘Corrine Corrina’ on that album, ‘cause that was such a favorite song of mine, since I was a child. So I asked Chubby Wise to come out and play on that song. . . . I made a big deal out of it and invited him out on stage, and the crowd liked him anyway because they knew who he was, he was a ‘star sideman,’ what we called ‘em. I counted off the song, and Chubby came in half-time! I went ‘One, two . . .’ and he went, ‘dah . . . . . dah . . . . . dah . . . . .’ half as quick as it should have been! [laughs] Finally we got it up to where it needed to be.”

Merle then sings “Every Fool Has a Rainbow,” which was the flip side of “The Fightin’ Side of Me” single. “TB Blues” was the classic Jimmie Rodgers ode to tuberculosis that Merle had left off his two-album Rodgers tribute LP from the year previous. Merle introduces the next song as a brand new Tommy Collins song, “When Did Right Become Wrong.” It was so new that Merle asked Tommy, who was in attendance that night, to come out and hold up a lyric sheet for him to read. The band is obviously unrehearsed on the song; there are a couple of obvious mistakes, but in the spirit of the “live” event, the song was left on the album, warts and all.

Much in the same vein, Merle then introduces his wife, Bonnie Owens, who steps up to the mike to sing “Philadelphia Lawyer,” a song written by Woody Guthrie but popularized by the Maddox Brothers and Rose. It was a perfect song choice for the live recording in Philadelphia. About halfway through “Philadelphia Lawyer,” Bonnie stumbles over the lyrics, something she never did. When asked why this song was left on the album, Merle had this to say: “I left it on there because it was spontaneous; it was a live album and that made it seem more live, more real. And it was so out of character for Bonnie to forget lyrics, because that was usually my job! We left it on there, because it was as real as it could be.”

The B-side of the LP begins with another Strangers instrumental, “Stealin’ Corn,” which they had recorded only two weeks earlier for their second solo LP. Bobby Wayne then steps up to the microphone to perform a humorous song he had written, “Harold’s Super Service.” One enduring question for many who listened to the Fightin’ Side of Me album was the identity of the banjo player. The uncredited banjoist turns out to be steel guitarist Norm Hamlet, who had been elected to play banjo in the band simply because he already had the thumb and finger picks on for playing steel.

Norm remembers that during the recording of the song “The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde” several years earlier, Glen Campbell had played a banjo part, which Merle then wanted to recreate live. Hamlet was drafted to learn the banjo, which he did in time to record with it for the studio session of “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am.” Hamlet brought the banjo on tour for several years to follow, but by the early 1970s had stopped bringing it on the road.

One of the most venerated traditions in country music, along with the comedy segment and the gospel song, was the impersonation of famous singers. Merle makes a point of saying that they weren’t regularly doing their impersonation segment anymore, but that they had gotten many requests to do it, so it was included on the recording. It seems funny now to think about an act that was polarizing the country with its political songs engaging in such throwbacks to the days of the tent shows, but it is important to remember that country music audiences even as late as 1970 expected such “bits” as part of their price of admission. One thing that can be said: Merle does frighteningly good impersonations. His take on Marty Robbins’s “Devil Woman” sounds like Robbins himself, and Hank Snow (who had opened the show that night, and was in attendance) must have gotten a kick out of Haggard’s version of “I’m Movin’ On,” which captures the essence of the Singing Ranger perfectly.

A nod to Johnny Cash’s big-selling live albums comes next, with Merle first tackling “Folsom Prison Blues” by himself, then bringing Bonnie up to sing Jackson a la Johnny and June Carter, and finally singing Cash’s version of “Orange Blossom Special,” all three eliciting wild applause from the audience.

Bobby Wayne steps up with Merle to ape Buck Owens and Don Rich on “Love’s Gonna Live Here,” with the Strangers easily nailing the Buckaroos’ trademark sound, Merle and Bobby doing a more-than-credible Buck and Don.

The album closes with three of Merle’s biggest hits: first his most successful ballad “Today I Started Loving You Again,” then the one-two sucker punch of “Okie from Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me” (these live versions from the Philadelphia recording would be released as a live single in 1972). Before the band launches in to “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” Merle gives an introduction to the song that lets the listener know that he is most certainly quite serious about his patriotic feelings, and his sense that America’s great freedoms were at risk. In the light of today’s political climate, it seems strangely innocent, especially Merle’s telling of Tommy Collins’s anecdote of losing recess privileges in school for dropping the American flag on the ground. Merle knew he had the audience eating out of the palm of his hand, and “The Fightin’ Side of Me” closes with wild applause.

“The Fightin’ Side of Me was a big album. I think it sold seven or eight hundred thousand pieces,” Merle remembers. “That wasn’t bad for a country boy that was competing with the Beatles on Capitol Records.”

LAND OF MANY CHURCHES

Most country music stars, if they are in the business long enough, eventually make a gospel album. Merle Haggard is no exception, but when he decided to make a gospel album, it was one of the most ambitious projects he had undertaken, and certainly the most involved live recording project he has ever done in his entire career.

By 1971 Merle Haggard had completed an impressive number of different projects. Not only was he a major country music superstar with a long list of best-selling singles and albums, but he had also done two live concert albums and tributes to his heroes Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills. It is obvious in hindsight that this was a man at the height of his creative peak, looking for new directions in which to focus his energies.

Instead of the quickie gospel album typically churned out by most country superstars, Merle decided to do a double album, recorded live at no fewer than four different places of Christian worship across the United States. The resulting album, Land of Many Churches, is an underappreciated document of the white gospel tradition, more like a field recording that happened to feature country music star Merle Haggard than the other way around.

There are two types of country music fans: those who appreciate gospel music and those who can’t stand it. The former group will find the familiar verses and shape-note harmony singing comforting, and will appreciate Haggard’s authentic contribution to the gospel genre. Those in the latter group should listen to the gospel recordings before dismissing them. Haggard brings the same soul and conviction to his sacred music as he does to his secular performances, and Land of Many Churches is a fine Merle Haggard album with many stellar performances.

Gospel albums are notoriously poor sellers, which makes it all the more surprising that Capitol Records would agree to make four different trips to four different remote locations with their mobile recording truck, but Merle Haggard could do whatever he wanted at this stage in his career. Capitol A&R man Ken Nelson only remembers that he thought a gospel album would be a good “catalog” album for Haggard (an industry term meaning that over the lifespan of a very successful artist, any album in their catalog will eventually be a good seller, even if it sells poorly upon initial release).

This was the 1970s, after all, an era that will never be equaled in the recording industry for inflated budgets and overblown productions. Today no artist could convince a major label to release a double album of gospel music, but in the 1970s double and triple albums were de rigueur for any successful rock or pop act. In that light, it is admirable that Haggard used his success, and Capitol Records’ financial backing, to make a double-album Jimmie Rodgers tribute and a double-album live field recording of sacred music, both unlikely projects for a star of Haggard’s stature.

Merle Haggard: “Some things are just about the art, the content was important to me, to be done that way. It was a live album project idea that I thought was necessary, and nobody seemed to disagree, they thought it would be a great ‘catalog’ record—not something that would jump out and sell a lot of records, but then again it might, you know? So, sometimes you go to make records, and you do it for other reasons than striving for a hit.”

The first recording session was on November 22, 1970, at Big Creek Baptist Church in Millington, Tennessee, a suburb of Memphis. Merle had arranged for the Carter Family to come and sing on the album. By 1970 this included original member “Mother” Maybelle Carter and her daughters Anita and Helen—June, now June Carter Cash, had left the group to tour full time with her husband Johnny Cash’s touring road show.

The segment recorded at Big Creek Baptist Church, other than the presence of its famous guest stars, was absolutely representative of almost any small-town country church in the South. Reverend Jimmy Whitlock introduces the album with typically dry country wit. The congregation begins the service by singing “We’ll Understand and Say Well Done,” before bringing Merle up to sing a medley of Thomas A. Dorsey’s “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” and “Jesus Hold My Hand” (the first of three Albert E. Brumley compositions to be recorded that day).

An interesting story surrounds the recording of the next number, the traditional gospel standard “Precious Memories.” All those who were present when the following incident happened swear to the fact that it really happened. Whether or not it was a simple technical glitch or divine intervention, it makes for a good story. Merle remembers: “We had a real chilling thing happen down there. We rented recording equipment in a truck pulled up next to the church, and microphones all running in through the door. We had the audience come in, and the church people, and we had different microphones on all the instruments, and tried to get separation, and it wasn’t much good. We did a cut on ‘Precious Memories,’ and I told the people in the church, give me a moment, I’d like to run out to the truck and see how that sounds, to have an idea whether or not we were getting anything good. So I went out to the truck and we played this take back.

“When we played the tape, there was this enormous choir of people, it sounded like a thousand people singing with us on this ‘Precious Memories’ thing, and I said, ‘What is that? Leakage?’ I thought the audience must be singing along with us. Everybody’s face turned white. We stopped the tape, and we said, let’s listen to that again, and when we played it again, it was gone! There was four people listening—there was myself, Fuzzy, Lewis Talley, and the representative for Capitol Records, George Richey [who would become Tammy Wynette’s fourth husband, after George Jones, in 1979]. I’m telling you, the hair stood up on the back of our necks. But we all had heard this sound, like you cannot believe, it sounded like a million angels. It’s not what you hear on the record, it’s something I can’t properly describe, but I never will forget it.”