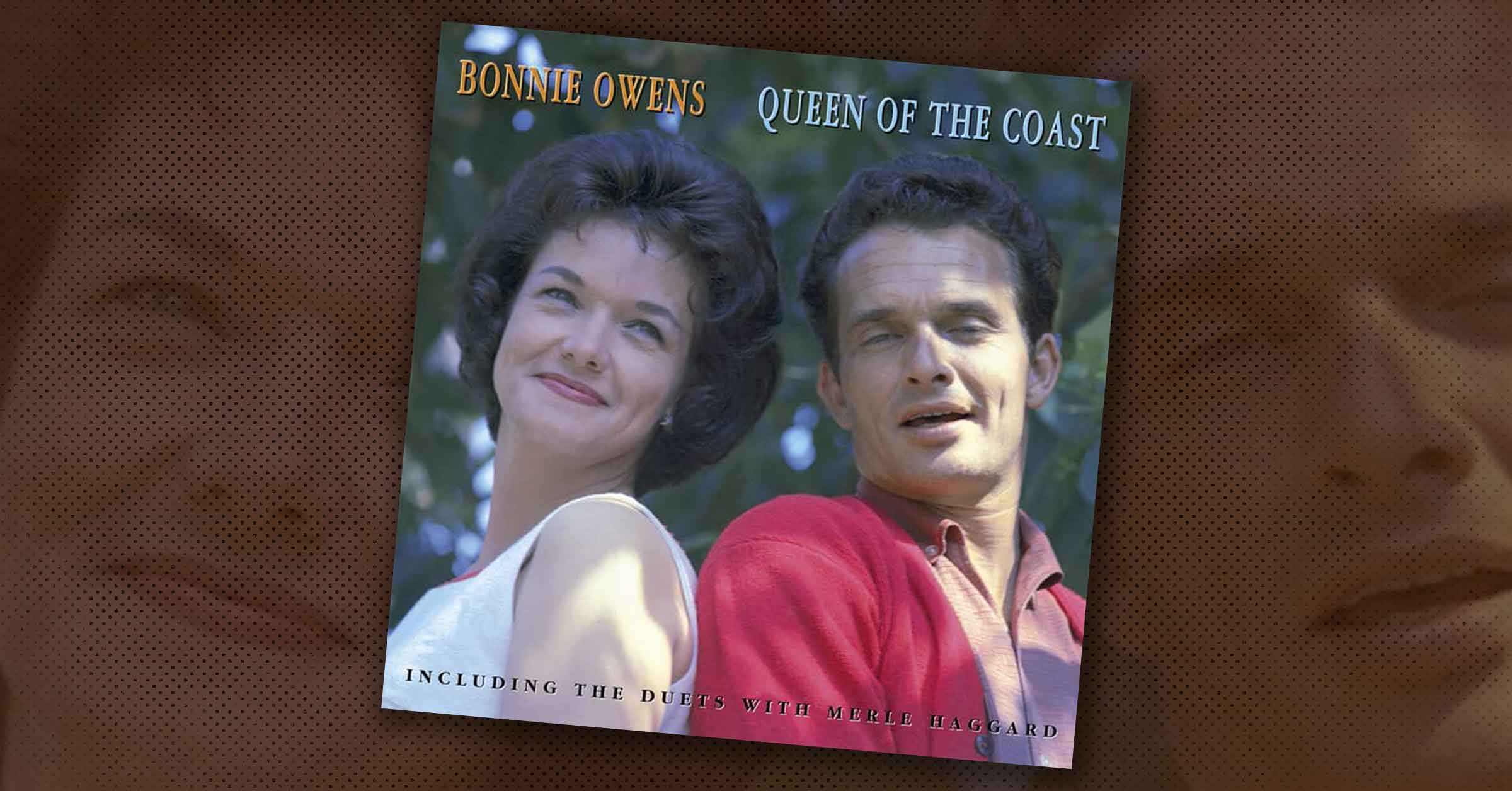

Liner notes for Bonnie Owens: Queen of the Coast , Bear Family Records

Originally published in 2007

Bonnie Owens, a fine country singer and songwriter in her own right, will forever go down in history as the woman who was married to both Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. Although this association alone would get her mentioned in the Country Music Who’s Who, it is also true that as a solo performer Bonnie Owens recorded an impressive body of work, enough material to make up the box set that you are now holding. Whether or not she would have been more or less famous had her life not been intertwined with two of country music’s biggest giants is a mystery, and even though she never had any huge hits to her name, Bonnie Owens is still known today as one of the genre’s finest underrated female singers.

Bonnie Owens was a woman everyone liked; not one person has anything bad to say about her. Over and over again, that sentiment was echoed by every single person interviewed for this box set, not only Merle Haggard and her sons with Buck Owens, Buddy and Mike, but also people that Bonnie met only in passing.

Bonnie would ultimately find her greatest success as Merle Haggard’s harmony and duet singer, a job she would keep long after her marriage to Merle had ended. It was this professional role that most country music fans and historians will forever associate with her, but on her own she left behind an impressive discography of singles and albums that place her as one of the most important female artists of the West Coast brand of country music that came to be known as the Bakersfield sound.

This box set represents everything that Owens ever recorded as a solo artist in her golden era of 1953 to 1971, from her first single on the tiny Mar-Vel label, through one-offs on small labels like X, Del-Fi, Pike, and fine early efforts for the Tally label of Bakersfield, to her six albums that she recorded for Capitol Records. When added to the incredible volume of work that she recorded with Merle Haggard during their forty-year association, it becomes apparent that Bonnie was one of the most recorded female singers in country music history.

So why didn’t she become a star? It’s hard to pinpoint exactly why it never happened for her. If you ask the key players in the Bonnie Owens saga, a complex picture emerges, with no clear answers.

Merle Haggard: “I have no doubt that my success overshadowed Bonnie—it had to. Bonnie would be the last one to bring that up. She never complained. We were married and she was happy to tour and sing and write with me.”

Fuzzy Owen: “There are a lot of great singers who never made it big. I think Bonnie’s problem was that she never had that song, that one hit song that would have made her.”

Ken Nelson: “Bonnie’s problem was that she was timid—she was just too darn shy.”

Michael Owens: “Mom had the talent to be a recording star, but she just didn’t have the cold heart and the cutthroat attitude that it takes to make it.”

We’ll never know the real reason why Bonnie didn’t make it big on her own, but the fact remains that she was one of the finest female country singers of all time. The recordings on this box set attest to this fact.

PART ONE: THE EARLY YEARS

Bonnie was born Bonnie Maureen Campbell on October 1, 1929, in Oklahoma City, the fourth of six girls and two boys in a typical Depression-era family. Like many families of the day, they worked the land as sharecroppers and did lots of other odd jobs to make ends meet. The family moved to Blanchard, Oklahoma, when Bonnie was just a baby, and that is the town that Bonnie usually cited as her hometown. In those Dust Bowl hard times, the family also moved around to Middleburg and Tuttle, Oklahoma, and eventually migrated to Gilbert, Arizona, near Phoenix.

Bonnie’s father, Wallace Campbell, was a jack of all trades and worked many different jobs, including stints as an iceman and then as a carpenter at the nearby Williams Air Force Base. Wallace played fiddle, piano, and harmonica, and he sang; he loved music and he fostered the musical abilities of all the kids in the family. Although he never played professionally, Wallace was by all accounts Bonnie’s first musical inspiration.

From a very young age, Bonnie was always singing. Her sister Betty recounts that as a little girl, Bonnie talked endlessly about wanting to be a singer. She was fond of yodelers like Patsy Montana, and she practiced yodeling constantly. An early family memory of Bonnie is of her singing while standing on bales of hay in their barn, using a broomstick as a microphone. A typical rural family, the Campbells listened to the Grand Ole Opry on the weekends, and country music singers were the centers of their musical universe. Bonnie’s sister Loretta remembers that “there was always music around us; we were surrounded by music.”

Bonnie was so sure about her future as a singer that she attempted to drop out of school in the seventh grade. Her father talked her into returning, which she did, even though it meant starting over and repeating the seventh grade. Bonnie’s lack of interest in school was so intense that she failed the eighth grade, which suited her just fine, as the setback landed her in the same grade as her sister Betty, who was two years younger. Betty remembers that one of the only things Bonnie liked about school was the orchestra, where she played both the trombone and French horn. She also sang in some of the school assemblies. Ultimately, their schooling mattered little because both Bonnie and Betty would drop out of high school in their junior years.

Bonnie’s father suffered the first of many heart attacks in the late 1940s, and on doctor’s orders to go to a milder climate, he moved the family to the Oakland/Alameda area (near San Francisco) in 1949. He died in 1958, after years of bad health. Bonnie, meanwhile, stayed in Arizona because she had fallen in love with a man named Buck Owens.

PART TWO: ENTER ALVIS “BUCK” OWENS JR.

Years before the hit records, decades before his Hee Haw television stardom, Alvis “Buck” Owens Jr. was just another hardscrabble hillbilly kid in love with music, with a head full of what seemed at the time like unreasonable dreams of stardom. He was six weeks older than Bonnie (Buck’s birthdate was August 12, 1929) and born in Sherman, Texas, but living in Mesa, Arizona, since 1937. Buck could pick a hot guitar, and he wasn’t a bad singer either. He worked picking oranges during the day and played music on the weekends with a duet act known as Buck and Britt (featuring Buck’s friend Theryl Ray Britten as Britt). The pair had a fifteen-minute radio show on KTYL in Mesa, which made them famous, at least to their friends and family members.

Bonnie met Buck at the Mazona Roller Rink in Mesa around 1945, when she was just fifteen or sixteen years old. Bonnie’s sister Betty recounts that the two girls would take the bus into Mesa to go roller skating, which in their teenage years was their only form of socializing. Buck knew Bonnie from school, but at first Buck’s romantic interest was directed toward Betty. One day Bonnie turned up unannounced at the Buck and Britt radio show. When Buck asked her why she was there, Bonnie replied that she was there to sing. Before that day Buck didn’t even know Bonnie had any desire to be a singer, and soon he began dating Bonnie.

Bonnie was included in Buck’s next musical endeavor, a local combo headed by gas station owner “Mac” MacAtee called Mac’s Skillet Lickers. The group was a typical hillbilly act of the day, with Buck playing steel guitar and Bonnie contributing vocals where needed. It was the first real professional band either of them had been in, and it gave both of them invaluable experience.

Mac’s Skillet Lickers are rumored to have recorded, either radio station acetates or an actual 78 rpm record release, but nothing has turned up, even after a search through Buck Owens’s music vault. At the time of this writing, there is nothing to document what the band sounded like, although a good guess would be the Maddox Brothers and Rose, then one of the biggest acts on the West Coast. Rose Maddox was one of the most popular and influential female country music singers in those years. Far from the demure, submissive female singers who were popular in the Southern states, Rose was a brash-voiced honky-tonk queen who could hold her own around a group of rowdy boys and whose loud nasal drawl could cut through a band of electrified instruments and a set of drums. She influenced an entire generation of female country singers who owed less and less to the old school of Kitty Wells and Patsy Montana and more to the rowdy rhythm and blues singers of the post-World War II era such as Ruth Brown and LaVern Baker.

In the late 1940s the Maddox Brothers and Rose also featured a new teenage guitar sensation by the name of Roy Nichols. Though young and fairly inexperienced, Nichols could dash off hot jazzy licks in the style of Jimmy Bryant and Junior Barnard. His presence with the Maddox Brothers and Rose was positively electrifying to a new generation of young guitar players, after the days of Gene Autry strumming open chords on an acoustic guitar, at the dawn of a new world where electric guitars could bring jazz into country music.

One memorable night, the Maddox Brothers and Rose, featuring Roy Nichols, played a local dance in Chandler, Arizona. In the audience were a teenage Buck Owens and Bonnie Campbell. In an interview with Robert Price published in the Bakersfield Californian, Bonnie remembered, “I never took my eyes off Rose Maddox—and Buck never took his eyes off of Roy Nichols.” Roy Nichols, of course, would eventually wind up being Merle Haggard’s guitar player for more than twenty years and is the lead guitarist on most of the tracks in this box set.

Buck married the four-months-pregnant Bonnie in January 1948, and soon they had two baby boys, Alan Edgar “Buddy” Owens, born in May 1948, and Michael Lynn Owens, born in March 1950. In interviews Bonnie would always say that her boys were her proudest accomplishment.

The marriage had its problems from the beginning. The young couple struggled to make ends meet, and soon after Michael was born it became obvious the union was not going to last. Bonnie moved to the Bakersfield area, where Buck’s aunt and uncle, Vernon and Lucille Ellington, had offered to help take care of the boys. Buck followed soon after, with his parents in tow. Amazingly, Buck and Bonnie had an amicable parting and remained friends. They wanted to give their two boys the best possible upbringing and worked together to share responsibility for their care. For the time being they were separated, but they remained married since neither of them could afford a divorce.

PART THREE: BAKERSFIELD

Bakersfield is the place in California where a country person can feel right at home. Miles away physically and culturally from Los Angeles and San Francisco, it was a destination for Okies and other migrant workers. With its oilfields, cotton fields, and other agricultural industries, work was plentiful, if not financially rewarding. Many of the farm workers lived in labor camps, tent cities, and other temporary housing that allowed them to follow the crops by the season.

With the influx of hillbillies, Mexicans, African Americans, Native Americans, and Chinese into the region, a new “crop” of music came into being that was as much a melting pot as the other facets of this new society. There was country music, to be sure, but it was a different kind of country music. Loud, electrified, and exciting, new acts such as Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, Spade Cooley’s Orchestra, and the aforementioned Maddox Brothers and Rose brought a completely different style to the region. It was a strong foreshadowing of what would ultimately be called rock ‘n’ roll, but in the late 1940s and early 1950s it was simply called hillbilly music.

Bakersfield developed a lively music scene centered in the rough dives and juke joints frequented by these new workers. Places like the Lucky Spot, the Clover Club, the Barrelhouse, and the Blackboard Cafe had live music seven nights a week. Big shows would come touring through town at places like the Rainbow Gardens and the Pumpkin Center Barn Dance.

Bonnie Owens found herself working as a carhop at a hamburger drive-in located at the intersection of Union and Truxton. Buck’s aunt Lucille cared for the boys during the day while Bonnie worked. Bonnie was already known around town for her singing talent, having already done a guest spot or two at the Blackboard Cafe and the Clover Club. Buck, in the meantime, had become lead guitarist for Bill Woods and his Orange Blossom Playboys, who played six nights a week at the Blackboard Cafe.

One day Thurman Billings, owner of the Clover Club, stopped with his wife at the drive-in asked if Bonnie would be interested in working at the Clover Club as a cocktail waitress. He also mentioned that anytime she wanted to sing at the club, she would be welcome. Bonnie’s sister, Betty, was already a waitress there, so Bonnie accepted the offer.

Bonnie became known as the singing waitress, a nickname that stuck for years. When she worked a shift, several times a night the house band would get Bonnie up to sing. It was great experience for her professional singing career, but terrible for her waitressing job—she lost tips every time she got up on the bandstand.

The challenge of being a single mother in the early 1950s was fraught with huge obstacles for Bonnie, but she never let anything stop her from taking care of her boys, or from pursuing her musical career. Buddy and Michael remember that they literally had dozens of babysitters who took care of them while their mother worked at night. Bonnie never had a car, and the family constantly moved from place to place. It was a hand-to-mouth existence, yet Buddy and Michael remember that whatever they lacked in money, Bonnie and their relatives made up in love and devotion for the two young boys.

It was while working at the Clover Club that Bonnie met a young steel guitar player by the name of “Fuzzy” Owen who had just returned from the Army.

PART FOUR: “FUZZY” OWEN AND TALLY RECORDS

Although he is barely mentioned in most history books, Charles “Fuzzy” Owen was every bit as important to the history of Bakersfield country music as his much better known peers Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. And, along with Buck and Merle, Fuzzy was the other important romantic and professional partner in Bonnie Owens’s career.

Fuzzy Owen, no relation to Buck, hailed from Arkansas and even today the years have not softened the Arkie lilt to his accent. After moving to Bakersfield in the late 1940s, leaving for the army, and then returning around 1952, Fuzzy began playing steel guitar and singing in local bands. He was by all accounts a talented steel guitarist and a good vocalist, but his greatest talent would come to be as a manager, recording studio engineer, record label owner, spiritual advisor, and generally tireless promoter of country music around Bakersfield. He is credited with starting the career of Merle Haggard, and he has been Merle’s manager from the beginning until the present day.

Fuzzy came to know Bonnie Owens soon after her arrival in Bakersfield; the town was small and the music scene highly incestuous. Buck Owens was immediately snapped up by Bill Woods and His Orange Blossom Playboys as a hot young lead guitar player and Fuzzy and Buck played together on Tommy Collins’s highly influential recordings for Capitol in the early 1950s (the first time that any of these men ever set foot in a professional studio, not to mention their first contact with their future employer, Capitol Records, and Capitol’s A&R man Ken Nelson).

Fuzzy was playing steel guitar in the house bands at such Bakersfield hot spots as the Lucky Spot and the Clover Club, and soon he and the “singing waitress” began singing and playing together through their constant contact. When Bonnie and Buck separated, Fuzzy and Bonnie began a romantic and professional relationship that would continue for more than a decade. It was Fuzzy who eventually helped Bonnie through the legal process of getting a divorce from Buck.

An interesting side note is that Bonnie’s sister Loretta, who had come to Bakersfield in the mid-1950s, wound up marrying Fuzzy’s brother Mack, who also played steel guitar with several local groups, including Henry Sharpe and the Sharp Shooters.

One of the earliest records made in Bakersfield was also the first record for both Fuzzy and Bonnie Owens. Although historically significant, it couldn’t have made less of a dent upon release—a small beginning for what would be two long careers. “A Dear John Letter” was released in late 1952 or early 1953 on the Mar-Vel label (a Bakersfield backyard endeavor not to be confused with the comparatively huge Mar-vel label of Hammond, Indiana). This was the original version of the song by Billy Barton, known to many as “Hill-Billy” Barton, that was made famous shortly thereafter by the cover version released later in 1953 by Ferlin Husky and Jean Shepard. Fuzzy remembers that the label was co-owned by Barton, and that they recorded it in a small basement studio containing one microphone into a small portable reel-to-reel tape recorder. Although Fuzzy and Bonnie’s version would disappear quickly in light of Ferlin and Jean’s hit, it marked an important step for both of the young singers—the first time they saw their names on a record label and held the results in their hand (Fuzzy also learned a thing or two about the music business when he and Lewis Talley procured the publishing rights for the song from Barton-Talley, trading his 1947 Kaiser as his half of the deal).

Bonnie and Fuzzy’s record of “A Dear John Letter” b/w “Wonderful World” was released twice, not only on Mar-Vel but also the Grande label. It is unknown why it was released twice, but the sales of both releases were minuscule, and today both are exceedingly rare.

Also in 1953 an enterprising disc jockey in Bakersfield named “Cousin” Herb Henson started a popular local television show called Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post. The show ran for more than ten years until Henson’s untimely death in November 1963 of a heart attack, and it provided valuable experience to many musicians and singers starting out in the business, most of whom were drafted straight from the Clover Club house band. Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post helped launch the careers of Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, Roy Nichols, Billy Mize, Cliff Crofford, Lewis Talley, Tommy Collins—and Fuzzy and Bonnie, who became regulars on the show, dubbed “our lovebirds” by Cousin Herb.

The exposure on Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post gave Fuzzy Owen and Bonnie Owens valuable local celebrity, which lifted them above the drudgery of cocktail waitressing and five-hour local bar gigs. Cousin Herb also provided a valuable service in networking Bakersfield artists to record labels looking for new hillbilly talent.

In the halcyon days of the early 1950s, very few of the Bakersfield artists were ready for Capitol Records, though most of them were eventually associated with the label. Tommy Collins, Ferlin Husky, Jean Shepard, and Cousin Herb himself were the only ones from the Bakersfield area recording for Capitol in the early ‘50s, but many of the other artists were making records for smaller companies, getting exposure any way they could.

One such label was X Records, a tiny subsidiary imprint of RCA Victor. Though it was small, the label had some success with Terry Fell, another West Coast hillbilly singer, who had several small hits such as “Don’t Drop It” and the original version of “Truck Driving Man,” a standard written by Fell and later recorded by Bill Woods and Buck Owens. For further examination of these influential early records, check out Bear Family’s Terry Fell compilation, Truck Driving Man, BCD 15762.

Bonnie Owens got the chance to record one session for X Records in April 1954, resulting in four songs, released on two singles. Three of the songs were Bonnie solo numbers: “I Traded My Heart for His Gold,” “Take Me,” and “Just a Love for Someone to Steal.” Following in the footsteps of “A Dear John Letter,” Fuzzy and Bonnie also recorded another duet, “No Tomorrow.” Fuzzy remembers that Bonnie had planned to overdub the harmony part on “No Tomorrow” herself, but she and Fuzzy had cut a demo of the song together, and the label wanted them to duplicate what they had done on the demo. The recording took place at Radio Recorders in Hollywood, but no Hollywood session musicians were employed. The record featured Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post regulars as backing musicians, including Buck Owens on lead guitar, Bill Woods on piano, Lewis Talley on rhythm guitar, “Jelly” Sanders on fiddle, and local country bassist “Red” Murrell.

Fuzzy and Bonnie didn’t get rich or famous from these two singles, but they did get more exposure and a bit more cachet around Bakersfield as not just television stars, but now recording artists as well.

A quote from Bonnie illustrates the order of the day: “I did what was needed and I did what I could. It was a great time. We thought we were as big as Nashville. We didn’t have their recording studios and we didn’t have the big radio stations, but we had the thing that was more than anything: We had the music.”

After a good number of sessions as a studio musician for Tommy Collins, Jean Shepard, and others, Fuzzy Owen took what he knew from observing the sessions, along with knowledge he had gleaned from reading books about electronics and sound reproduction, and put together his first studio in Bakersfield for the sole purpose of releasing music on his friend Lewis Talley’s new label, Tally Records. The studio didn’t amount to much—it was no more than a primitive mono Stancil-Hoffman tape recorder and one microphone setup at first—but eventually Fuzzy turned it into Bakersfield’s first real recording studio, with equipment to rival that of the big boys down in Hollywood.

The first Tally single was a 1956 duet between Bonnie Owens and JoAnn Miller, billed as the Kern County Sweethearts. The songs were “Father” (featuring a recitation by Lewis Talley) b/w another Buck Owens composition, “Please Don’t Take Him from Me.” Like her previous releases, the record sold a few hundred copies off the bandstand but failed to make a dent beyond Bakersfield. It was an important milestone, however, in that it was the first release on the Tally label, which would be important to many other Bakersfield musicians (and would eventually release the first three records by Merle Haggard).

Given the popularity of Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post, the entire cast was rounded up to produce a soundtrack album around 1958 or 1959. It was recorded at Fuzzy’s studio on Hazel Street and released on Tally Records and sold over the airwaves as a promotional item. It is exceedingly rare today and exists as a wonderful time capsule for the burgeoning Bakersfield scene.

Bonnie cut three tracks for the album, all included here. With Fuzzy she recorded a duet of “Looking Back to See,” a number originally done by the Browns and covered by a number of acts, including the Collins Kids. Los Angeles studio ace Joe Maphis played lead guitar on the track, to great effect. On her own she recorded “That Little Boy of Mine” and “Wait a Little Longer, Please Jesus,” a composition by early Capitol artist Chester Smith—another San Joaquin Valley country singer—coauthored with Hazel Houser. Slowly but surely, this release brought Bonnie slightly more name recognition, and her career inched forward.

Another mover and shaker for country music around southern California was the young and enterprising Gary Paxton, who had scored big with the novelty rocker “Alley Oop,” a hit for the Hollywood Argyles (written by Bakersfield singer Dallas Frazier) in 1959. Paxton took an interest in country music, eventually building a huge, competitive, professional multitrack recording studio in Bakersfield and cutting for his own Bakersfield-International label a host of records that would be important in the birth of the country-rock genre in the late 1960s.

At the beginning of the decade, though, Paxton was starting his career in country by producing artists for other labels, and Bonnie Owens was one of the first. Paxton produced a single for Bonnie, “Just for the Children’s Sake” b/w “This Other,” released on Del-Fi in May 1960. The record certainly had the commercial sound of a hit, very much recalling the popular “Ray Price shuffle” sound of the day, and it featured the top Hollywood session musicians Billy Strange on guitar, Ralph Mooney on steel guitar, Gordon Terry on fiddle, and George French Jr. on piano (the latter three would wind up spending years as part of Merle Haggard’s backing band, the Strangers). Although the Del-Fi record sounded like a potential hit, it again sank without a trace, and today is quite rare. An interesting side note is that this recording was a split session with Don Markham, who was recording two sax instrumentals that day for a Donna label 45 also produced by Paxton. Markham would eventually go on to play sax and horns for Merle in the 1970s.

Bonnie did not enter a recording studio for two more years. Her next recording was merely as a duet partner on an obscure novelty tribute disc, but it is included here for completists. Tommy Dee, born Thomas Donaldson, was a San Bernadino–area disc jockey who achieved modest fame in 1959 with the morose tribute record “Three Stars,” an ode to Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens, who had been killed in a plane crash in February of that year. He was another southern California hopeful who would make a rash of singles over the years—some pop, some country, although ultimately “Three Stars” would be his only real success.

When the plane carrying Hawkshaw Hawkins, Cowboy Copas, and Patsy Cline crashed on March 5, 1963, you couldn’t blame Tommy Dee for grasping the opportunity, especially since all his follow-up releases had failed. “Missing on a Mountain” (released on the small Bakersfield label, Pike) is just “Three Stars” with new lyrics about the latest trio of musical plane crash victims, a country-western version of the earlier hit, as it were. Bonnie supplied the female vocals and Tommy Dee reprised the recitation. Bonnie was not on the flip side of the record. Overall it was fairly forgettable and deservedly sank without a trace.

During this time, Bonnie Owens was watching her ex-husband Buck Owens begin to achieve unprecedented success for a Bakersfield artist. Though Tommy Collins, Jean Shepard, and Ferlin Husky had achieved major-label status and even had a few hits, no one from the area had had the sort of success that Buck was starting to achieve. After a few misses, Buck had begun to have hit after hit, and essentially didn’t stop having hits until the mid-1970s, and even then only because of overexposure caused by his weekly appearances on the Hee Haw television show. Buck had gone from being a lead guitar player in a local bar band to a nationally known singer in just a few years, and he was now a shooting star headed straight up, soon to become one of the biggest-selling country artists of the 1960s. A little-known fact is that Bonnie actually toured with Buck as a backup singer in 1963, but it was short lived and soon she was back in Bakersfield working as the “singing waitress.” As Bonnie watched “Missing on a Mountain” fade away with no impact, she must have felt that her career was heading nowhere. In nine years she had recorded only a handful of unsuccessful singles. She was appreciated and well liked around Bakersfield, but outside of Kern County she was unknown.

In the meantime, Fuzzy Owen had purchased Tally Records from his cousin Lewis Talley and become considerably more active in releasing and promoting records. After releases by himself and Lewis Talley as well as other local artists such as Cliff Crofford and Cousin Herb, eventually Fuzzy asked Bonnie to make records for Tally.

Bonnie’s first release on the newly rejuvenated label was “Why Don’t Daddy Live Here Anymore” b/w “Waggin’ Tongues,” released as Tally 149. The dates are a little mysterious, since Fuzzy kept no records at all, but it was probably released early in 1963. It was quickly followed up by “Stop the World (And Let Me Off)” b/w “Don’t Take Advantage of Me,” also probably in the same year. Little is known about the sessions, but the musicians probably included Fuzzy or Ralph Mooney on steel guitar, Roy Nichols or Gene Moles on guitar, Jelly Sanders on fiddle, and Helen “Peaches” Price or Henry Sharpe on drums. Several other tracks were cut during these sessions; two were later released as a Tally single (“Lie a Little” and “I’ll Try Again Tomorrow”), and several others stayed in the vaults for the time being.

Although she had the famous last name of Bakersfield’s most successful export, Bonnie never marketed herself as Buck’s ex-wife. A decade had passed since their breakup, and she was determined that if she was going to make it, she was going to make it on her own. There was also a bit of confusion since Fuzzy’s last name was Owen (no relation). One telling Tally Records ad from the time advertises her as “Miss Bonnie Owens—to be known in the future as Miss Bonnie.”

Not long after her two singles, Fuzzy suggested that she record a duet with a new singer they were having a small degree of success with. The young man was a recent parolee from San Quentin; Bonnie had seen him many years earlier singing a few songs during intermission at a Lefty Frizzell show at the Rainbow Gardens. Since his release from prison, he had spent some time as a bass player both with Wynn Stewart and Buck, sung with a few local bands around town, and had been introduced to Bonnie during his recent guest appearance on Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post.

PART FIVE: ENTER MERLE HAGGARD

Merle Haggard remembers watching Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post in the late 1950s with his mother, Flossie. When the pretty young singer Bonnie Owens would come on the show, Flossie (who didn’t care for Merle’s wife at the time, Leona Hobbs) would comment to Merle, “I wish you could find a girl like that!” Merle could not have predicted the long association he would come to have with Bonnie, but fate brought them together for what turned out to be a decades-long singing partnership.

Merle Haggard and Bonnie hit it off right away. They weren’t romantically interested in each other, at least not at first—Bonnie was still Fuzzy’s girl, and Merle was still married to his first wife (the first of two named Leona). But there was no denying that when Merle and Bonnie sang together, the result was something magic. The singing partnership would last more than 40 years, through all sorts of personal and romantic relationships, and it ended only when Bonnie was physically unable to tour any longer.

As Merle put it in an interview with the Orlando Sentinel: “[Bonnie’s] got a real unusual voice. Once you hear her talk, you’ll remember her voice in the dark three hundred years from now.”

The first record that Merle and Bonnie cut together was part of a 1964 Merle session that also yielded one of his biggest early hits, “(My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers.” The session was held at URCON (United Recording Corporation Of Nevada) Recording Studios in Las Vegas, where Merle had been playing with Wynn Stewart’s band in a residency at the Nashville Nevada Club out on Boulder Highway. The band was Wynn’s house band: Roy Nichols on guitar, Ralph Mooney on steel guitar, Bobby Austin on bass, George French Jr. on piano, and Helen “Peaches” Price on drums. If the names sound familiar, that’s because Merle used this entire group a short time later after the Wynn Stewart residency ended as the first version of his touring band, named the Strangers after the song they cut that day.

The first song Merle and Bonnie recorded together was a Fuzzy original called “Slowly but Surely.” The other number was from the pen of Liz Anderson, who wrote “(My Friends Are Gonna Be) Strangers” and later “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive” for Merle. The song was “Just Between the Two of Us,” and immediately upon release as a Tally single, it was a smash hit.

Bonnie Owens, quoted in the Bakersfield Californian, remembered the Tally period: “We’d sent records to disc jockeys all over the country, and we’d include handwritten notes in each one,” Bonnie said. “I was in touch with every disc jockey in the country. When we started doing it, we’d put Merle’s record in with mine. It wasn’t long until I was putting my record in with Merle’s.”

Knowing they had a hit on their hands, Fuzzy took Merle and Bonnie back into the studio with the same band in December 1964, but almost immediately after “I Want to Live Again” and “A House Without Love Is Not a Home” were committed to tape, Ken Nelson of Capitol Records called Fuzzy Owen in Bakersfield. Nelson had tried to sign Merle Haggard the night of the recording of the Country Music Hootenanny LP at the Municipal Auditorium in Bakersfield in September 1963. At the time, Merle swore allegiance to Fuzzy and Lewis Talley—for their belief in him—and to Tally Records. Now that Merle had two top-forty hits, one top-ten hit for Tally, and a hit as a duet with Bonnie, Ken Nelson decided it was time to try a little harder.

“I Called Fuzzy,” Nelson recalls, “and I said, ‘C’mon Fuzzy, this is ridiculous. You’re holding back the careers of Merle and Bonnie at this point. Let me sign them to Capitol Records.’” Fuzzy, being a man of financial intelligence, realized that it was time to make a move. Fuzzy retained management of both Merle and Bonnie, wrote songs for both, leased Capitol the Tally masters, and took coproducer’s credit on all the future recording sessions, all of which he would continue after he found out that Merle and Bonnie had become romantically involved.

PART SIX: CAPITOL RECORDS

Capitol Records’ initial arrangement for both Merle Haggard and Bonnie Owens was to lease previously recorded Tally masters from Fuzzy. Any notion that Bonnie was signed only because she and Merle had recorded a hit duet together should be dispelled by the fact that the first Bonnie Owens solo LP, Don’t Take Advantage of Me, was released quite a bit before the Merle and Bonnie duets album.

“I signed Bonnie because of her talent, and I would have done so with or without Merle Haggard,” Capitol’s long-term country A&R man Ken Nelson claims. “Bonnie was a terrific singer, and the fact that she was involved with Merle had nothing to do with me keeping her on the label. In fact, I didn’t even know that Merle and Bonnie were involved until after they married. I always made a point not to involve myself with the artists’ personal lives—after someone told me not to sign George Jones because he was a drunk. I took their advice, and of course George’s next ten records were smash hits, so after that I never asked about any artist’s personal life.”

Don’t Take Advantage of Me was made up entirely of Tally masters, both the released singles and a half-dozen other unreleased tunes that Fuzzy had laid down in order to have a complete album to sell to Capitol. It included two songs cowritten by Bonnie: “Number One Heel” with Buck and “Don’t Take Advantage of Me” with sometime–Buck Owens bass player and “Buckaroo” theme song writer Bobby Morris. The album also had two numbers written by Fuzzy, “Why Don’t Daddy Live Here Anymore” (cowritten with Dallas Frazier) and “I’ll Try Again Tomorrow.” There was a song written by Merle, “The Longer You Wait,” and one Merle cowrote with Red Simpson (which Merle would have success with on his own), “You Don’t Have Very Far to Go.” There was even a cover of “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart,” the old Patsy Montana chestnut (with some amazing Roy Nichols guitar work livening it up considerably).

Don’t Take Advantage of Me was not a bad major-label debut album. It made number fifteen on the country album charts, a respectable figure for any “new” artist. It paled next to Merle’s immediate chart-topping success, but the fact remains that Bonnie held her own. She was voted top female vocalist by the Academy of Country Music in 1965, a real feather in her cap and one of the proudest achievements of her long career.

The romance between Merle and Bonnie, as detailed in Merle’s autobiography Sing Me Back Home, began with Fuzzy and Bonnie giving Merle a helping hand as his marriage to Leona Hobbs was ending. Bonnie was taking care of Merle’s kids, and Bonnie and Merle began to pour their hearts out to each other. Bonnie was sure that Fuzzy was seeing someone else (he was, in fact, seeing a woman named Phyllis, who later became his wife of forty-plus years and one of Bonnie’s closest friends), and Merle began to convince himself that he was in love with Bonnie.

Bonnie took a residency at a club in Fairbanks, Alaska, possibly to get away from her problems in Bakersfield, and she was gone for a few months in summer 1965. Bonnie’s absence made Merle’s desires intensify, and he developed a scheme to fly to Alaska and win her affections. After asking Fuzzy for Bonnie’s phone number in Alaska, Merle fibbed to Bonnie that he wanted to go there to get work and promote his records. She attempted to shut down Merle’s advances from the start, but he went back to Fuzzy and borrowed money, not mentioning that he was going to use it to fly to Fairbanks and try to steal his girlfriend. When Merle called Bonnie a second time, she told him not to come to Alaska if he had romance on his mind, but Merle was already in Seattle waiting on a connecting flight.

After he arrived, Bonnie got work for Merle at the club where she was performing but insisted that they remain platonic during his visit. After Merle came to her room at three in the morning and announced his undying love, Bonnie finally gave in and agreed that they had something special that couldn’t be ignored. The difficult part was letting Fuzzy know that Bonnie was now Merle’s girl. Merle called Fuzzy from Alaska and announced that he and Bonnie were getting married. As Merle wrote in his book, “As I hung up the phone I knew it would take one hell of a big man to be able to go on working as a team with us. Fuzzy was one hell of a big man.”

After returning from Alaska, Merle and Bonnie took a whirlwind trip to Mexico, and on the same day as Merle’s first release on Capitol, June 28, 1965, the two were married. Bonnie’s family tried to talk her out of it—they viewed Merle as an outlaw, knowing his ex-convict status, and thought that since Bonnie was seven years older than Merle, the marriage wouldn’t last—but she was undeterred.

As Merle put it in an interview with the Orlando Sentinel: “[Bonnie’s] got a real unusual voice. Once you hear her talk, you’ll remember her voice in the dark three hundred years from now.”

By the time that Merle and Bonnie’s album of duets, Just Between the Two of Us, was released in fall 1966, the two had settled into married life and Bonnie was touring as a full-time member of Merle’s band, the Strangers. The pair had also won the Academy of Country Music award for best vocal duet in 1965 and again in 1966, another impressive achievement for both of them.

Just Between the Two of Us was made up entirely of duets to capitalize on the hit single. About half of the album had been recorded before Merle and Bonnie were signed to Capitol. It was produced at URCON (United Recording Corporation Of Nevada) Recording Studios in Las Vegas and HR Studios in Hollywood in 1964 and 1965. When the decision was made to complete the album, Merle and Bonnie came in early August 1966 to the Capitol Tower in Hollywood. Merle had had session the day before.

Songs included the title song and two others by Liz Anderson, “So Much for Me, So Much for You” and “That Makes Two of Us.” Fuzzy Owen wrote a pair of songs, “Slowly but Surely” and “I Want to Live Again,” and ex-husband Buck also wrote two, “I’ll Take a Chance” and “Forever and Ever.” The pair re-recorded one of the numbers Bonnie had cut on the Cousin Herb Henson’s Trading Post soundtrack LP, “Wait a Little Longer, Please Jesus.”

As would become a tradition for all of Bonnie’s albums, a batch of cover songs were rounded up to round out the record. Songsmith Bill Anderson contributed “Our Hearts Are Holding Hands,” and Texas song pluggers Don Carter and Jack Rhodes (who wrote several rockabilly songs recorded by Gene Vincent and others) wrote “Too Used to Being With You.” Hank Williams’s “A House Without Love,” an old standard, was given a new Bakersfield treatment.

The difference between Merle Haggard and Bonnie Owens and singers like George Jones and Tammy Wynette, or Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton, or the other classic kings and queens of country music, quickly became apparent as Merle launched into the stratosphere with each successive release while Bonnie sold fewer and fewer records. Although she was touring with Merle and the onstage chemistry was there, she never had any big hits of her own. Ken Nelson kept her on the Capitol roster until 1970, but Bonnie became lost in Merle Haggard’s shadow, and her identity as a solo artist was eventually replaced by her role as Merle’s wife and backup singer. Their album of duets would ultimately be her highest-charting release, and soon the billing of the duets became Merle Haggard, singer, with his wife, Bonnie Owens, on backing vocals.

Perhaps the liner notes from Bonnie’s Don’t Take Advantage of Me album illuminate the situation. A quote from Merle Haggard: “Bonnie’s the type of person who takes pleasure in doing things to please other people, so this album will make her very happy, because it’s going to please lots of people.”

Bonnie gave herself over completely to Merle Haggard and his career. Several of her quotes in the Untamed Hawk Merle Haggard box set liner notes (as told to author Dale Vinicur) give an idea of their relationship:

“We sang together first, but it didn’t go farther than that for a long time. He was married, his life was too complicated. I also thought he’d never settle down. His talent didn’t need help; he just needed discipline.”

“When we got married, he said, ‘Bonnie, don’t ever satisfy me, or I’ll be gone.’”

“There was a time, probably about the first three years we were married, that I was number one in Merle’s life. The rest of the time there may have been about fifteen others who were ahead of me.”

“I’m still not sure that [Merle] was ever in love with me, but I’ve never doubted that he loved me. I was a phase in his life, an important phase, I hope, but I thought of it as a partnership. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Well, if it lasts three weeks, it lasts three weeks.’”

Bonnie continued to make solo records even after Merle’s career went through the roof. As Ken Nelson explains, “Once an artist was on Capitol Records, they were allowed to stay on Capitol as long as their records sold enough to pay for themselves. If an artist began to lose money for the label, the accounting department would inform me that they had to be let go. Bonnie never had huge-selling records, but she definitely sold enough to keep her making records for several years.”

Most, if not all, of Bonnie’s sessions were scheduled to coincide with Merle’s sessions, using the same band, auxiliary session musicians, and studios. Sometimes this was done on purpose, or, as Merle explained, “Sometimes I would have a cold or a sore throat, and I’d say, ‘Bonnie, why don’t you cut a couple tunes.’”

Another important relationship began during this time, as Bonnie became not only Merle Haggard’s wife and duet singer, but also his invaluable songwriting partner. Usually the songs were thought up and written by Merle, sometimes with assistance from Bonnie, but most importantly she was there to write everything down. When the mood struck, Merle sang the lines and Bonnie transcribed them, whether they were on the tour bus, in a hotel room, or anywhere else.

Merle described the process in his My House of Memories autobiography: “Bonnie and I were more effective as a songwriting team than ever. She’d suggest where I might change a song’s arrangement, or another verse, or another repeat of the chorus. There is a certain satisfaction a man gets from working with the woman he loves, who was brilliant and had a formal education, to boot.” Bonnie received partial songwriting credit on only a few of Merle’s songs (most famously “Today I Started Loving You Again” (Bonnie received cowriter’s credit for convincing Merle to omit a verse), but most agree that without Bonnie there to get it all down, many of Merle’s classic songs would have gone unwritten.

Buddy Owens adds: “After a while, her goal became making Merle Haggard the biggest star that he could be. She knew she had a valuable part in that and was always willing to do whatever it took to make Merle a bigger star.”

Merle and Bonnie moved into a house in Bakersfield, along with Bonnie’s sons, Buddy and Michael, and for the time being things were about as tranquil and domestic as they ever would be in Merle’s turbulent life. Buddy and Mike remember thinking they had hit it rich because Merle had a car. Merle and the boys also shared a love for fishing in the Kern River, which would eventually get Michael in trouble at school when he showed up late too many mornings with the excuse that he had been out fishing with Merle Haggard. Michael caught the biggest rainbow trout of the year, and he remembers stopping with Merle at several musicians’ houses on the way home that day, including that of Blackboard drummer Henry Sharpe, to proudly show off the record-breaking fish. Merle had a passel of his own kids to worry about, but he looked after Bonnie’s boys as though they were his own. When Merle and Bonnie hit the road, the boys’ grandmother or one of the other relatives would look after them. It was an arrangement that worked, for a time.

Bonnie’s third album for Capitol, All of Me Belongs to You, was released in 1967. It was her first album done entirely at Capitol for Capitol, the first two having been combinations of old Tally masters with a couple of new sessions. This third album represented a hodgepodge of sessions, the first done at the Capitol tower in August 1965, and later ones in November 1966. It’s obvious from looking at the session sheets that Bonnie’s recordings were made with singles in mind; the LPs were assembled somewhat willy-nilly, with songs grabbed from various sessions to complete each album. Bonnie’s later albums robbed leftover tracks from earlier (sometimes years earlier) sessions.

All of Me Belongs to You contained eight tracks that had been previously released as (four) singles: “Souvenirs” / “Excuse Me for Living” had been released in November 1965, “What’s It Gonna Cost Me” / “You Don’t Even Try” had been released in July 1966, “Consider the Children” / “I Know He Loves Me” had been released in October 1966, and “Someone Else You’ve Known” / “The Best Part of Me” was released in March 1967. This was obviously the peak of Capitol’s push to make Bonnie a star, since releasing four singles in advance of one album was more than they had done before or would do again. Although none of the singles charted, the album reached number thirty-five on the country charts, which was respectable but hardly made it a best seller.

The title track was written by Merle Haggard, as were four other numbers on the album: “Someone Else You’ve Known,” “You Don’t Even Try” (cowritten with Fuzzy Owen), “Consider the Children” (cowritten with Dean Holloway, Merle’s good friend and bus driver), and “Will You Want Me Just as Much” (cowritten with Tommy Collins). Liz Anderson contributed “Excuse Me for Living,” Fuzzy Owen contributed “I Won’t Go Lookin’ for You,” and Haggard’s then-bassist Jerry Ward (real name Howard Lowe) wrote two numbers, “What’s It Gonna Cost Me” and “The Best Part of Me.” “What’s It Gonna Cost Me” was recorded on December 2, 1965, the day after Merle had recorded “Swingin’ Doors” with the same band, including Phil Baugh on guitar (who contributed some amazing chicken-pickin’ licks to “What’s It Gonna Cost Me”). Glen Garrison contributed “Any Part of You,” and “Souvenirs” was cowritten by Mary Ann Wills and former member of Dave Burgess of the Champs (“Tequila”).

“Any Part of You” and “Consider the Children” were recorded at the tail end of a marathon three-day Haggard session at the beginning of August 1966 that yielded “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive” and “Someone Told My Story” as well as most of Merle’s new I’m a Lonesome Fugitive album. In a reverse move, when Haggard and the Strangers entered the studio in November 1966, Bonnie recorded two sessions on November 14 and 15 that made up a large chunk of her All of Me Belongs to You album, followed by a Haggard session the following day on November 16 that yielded Merle’s next hit single, I Threw Away the Rose.

Merle and Bonnie also began sharing songs, and a number of these tunes were recorded by each of them at different times, but by all accounts it was a friendly situation between the newly married couple. Merle had recorded his composition “All of Me Belongs to You” four months prior to Bonnie, but his version came out after hers on his I’m a Lonesome Fugitive LP. The song “Gone Crazy” was actually recorded by Merle and Bonnie on consecutive days; both made it an album track. According to Merle, occasionally when he finished writing a song Bonnie would tell him she’d like to record it for herself. Occasionally Merle would decide to re-record the number, with the end result being a handful of songs that both he and Bonnie recorded.

Some interesting unreleased tracks have surfaced, heard here for the first time. “She Don’t Deserve You” was a fine ballad number cowritten by Buck Owens and Artie Lange. “Just for the Children’s Sake” was a re-recording of the Harlan Howard number Bonnie had cut for Del-Fi years before. And there is an earlier take of “The Best Part of Me.” There was a Nashville session in May 1967 that yielded the first cut of Delbert McClinton’s “If You Really Want Me to I’ll Go” (a hit at the time for Delbert as part of the Ron-Dels) and another Buck Owens tune, “Adios, Farewell, Goodbye, Good Luck, So Long.” Why these tracks remained unreleased is unknown; no one involved seems to remember, but it is likely that the band was on the road at the time and decided to stop in and try recording while they were in Nashville, and then were unhappy with the results. “If You Really Want Me to I’ll Go” was re-recorded for Bonnie’s next LP, but the earlier Nashville recording is heard here for the first time.

Capitol released two new singles on Bonnie in 1967. “I’d Be More of a Woman” / “Everything That’s Fastened Down Is Coming Loose” was released in August, and “Somewhere Between” / “Don’t Tell Me” came out in November. As with the previous batch of singles, none charted, but the next LP, Somewhere Between, managed to hit almost exactly the same position (thirty-four this time instead of thirty-five) as the last album did on the country charts. Again, it was respectable, garnering enough sales to keep Bonnie on the label.

Somewhere Between came out in early 1968 and marked Bonnie’s fourth album in as many years (which seems like a lot until you consider that Merle was recording a minimum of three albums a year during the late 1960s). The majority of it was recorded between July and September 1967, with a few tracks culled from sessions that had taken place in June and November 1966.

Again, husband Merle contributed several songs to the album, including the title track (“Somewhere Between”), “Whatever Happened to Me,” and “Gone Crazy” (cowritten with Bonnie). Harlan Howard, an old California friend of Wynn Stewart who was then having tremendous success in Nashville, was the writer of “I Wish I Felt This Way at Home,” and Bakersfield stalwart and family friend Tommy Collins wrote “Everything That’s Fastened Down Is Coming Loose” and “I’d Be More of a Woman” (both A and B sides of the most recent Capitol 45 release). Other songs on the album were written by Kay Adams (the female truck-driving singer and daughter of hillbilly singer Charlie Adams), who wrote the coyly titled “I Let a Stranger Buy the Wine” (for her own Alcohol and Tears album the year before). Merle Haggard’s bass player and drummer at the time, Jerry Ward and Eddie Burris, wrote “Don’t Tell Me.”

Seemingly as an effort to complete the album, perhaps strictly as filler, Bonnie dug out a few cover songs, including Don Gibson’s “Just One Time” and the old A. P. Carter / Roy Acuff warhorse “Wabash Cannonball,” both of which were jazzed up considerably with some great twin guitar work courtesy of Roy Nichols and pre-hitmaking session man Glen Campbell.

“Hangin’ On,” a song written by Buddy Mize and Ira Allen, had quite a story behind it. Originally recorded in the summer of 1967 by the Gosdin Brothers, Vern and Rex (the same Vern Gosdin who had several hits in the 1970s and 1980s, when he became known as “the Voice”), on Gary Paxton’s Bakersfield International label, the song became a breakout hit. Cover versions were soon coming out everywhere by numerous other artists, including Waylon Jennings (who titled an RCA album after the song), Johnny Darrell, and the Wilburn Brothers. There was a rash of female versions as well, by Jean Shepard, Kitty Wells, Loretta Lynn (with Conway Twitty), and Bonnie Owens.

Some confusion exists about the album’s title track, Somewhere Between, a love song cowritten by Merle and Bonnie, and another Haggard song, “Somewhere in Between,” which had inflammatory political lyrics vis-a-vis the left- and right-wing ends of the spectrum. The songs couldn’t be more different, but the BMI music publishing website mistakenly identifies them as being the same composition. While Haggard made headlines with his political and topical songs such as “Okie from Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me,” Bonnie Owens never tackled anything controversial in her life. Let there be no confusion: “Somewhere Between” is just another good honky-tonk love song, most assuredly not the politically provocative “Somewhere in Between.”

As with her previous albums, Somewhere Between was recorded using Merle Haggard’s band, the Strangers. Beginning with the September sessions, the steel guitar player on all Bonnie’s records would be Norm Hamlet, who joined the Strangers that summer (and remains in the band to the present day). Hamlet had cut his first session for Haggard the same day (September 18, 1967) as his first session with Bonnie, with “Sing Me Back Home” being the first Haggard hit he played on. Some of the other auxiliary musicians on the sessions at the time included James Burton, the famous session man who had played with Ricky Nelson and went on to play with Elvis Presley (he contributes phenomenal chicken-pickin’ to “Gone Crazy” and others); Glen Campbell playing guitar and singing background vocals; Bakersfield buddies Lewis Talley and Billy Mize (as well as Merle) on rhythm guitars; and Fuzzy Owen playing steel on a couple sessions in early 1967, after Ralph Mooney’s departure but before Norm Hamlet joined the band.

After several stops and starts, personnel changes, and other delays, the Merle Haggard road show really began touring full time in 1967, starting a grueling nonstop road tradition that continues to the present day. Life became a series of one-nighters strung together by endless hours on the tour bus. By all accounts, Bonnie loved it. Described by Merle as a “singer, nurse, psychiatrist, seamstress, and all-around den mother,” Bonnie Owens relished her position as the surrogate mom in a bus full of rough-cut men. According to Merle and other bandmates, Bonnie had absolutely no problems handling life on the road, and on several occasions showed the troupe how tough she could be.

Merle recalls: “Bonnie was the nicest, sweetest woman you’ve ever met, but I remember two times in particular where she got real mad. There were always women around, coming on to me, but most of the time Bonnie just stayed back and played it cool. I remember once at a dance at the old Fresno Barn, must have been about 1964 or 1965, there was a redheaded gal after me all night long. I mean, she wouldn’t let up, just pursuing me. Well, at the end of the night, when we were settling up with the owner, that ol’ redheaded gal come barging in the office. Bonnie grabbed the girl by the collar, opened the door and kicked her in the butt, all at the same time, and said ‘We’ve had enough of you tonight!’ [laughs] I also remember years later, we were crossing the English Channel going into France, and everybody got sick as a dog on the rough waters crossing the channel. Well, we were all laid out sick on the floor and this ol’ French woman comes around and tells us we have to get up. Bonnie let this woman have it—she cussed her out like you wouldn’t believe! Now, I don’t think you could find anybody to say anything bad about Bonnie Owens, but if you could find those two old gals, you might.”

With the new road schedule, Bonnie’s sessions became few and far between over the next year. A few songs were dashed out at the tail end of Haggard sessions in November 1967 and February and March 1968, enough to release a single in June, “How Can Our Cheatin’ Be Wrong” / “Yes I Love You Only.” The latter, an Ann Bruce composition, was recorded at the end of a three-day Haggard session in late January 1967 and early February 1968 that resulted in the number-one hits “The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde” and “I Started Loving You Again,” and put on the B-side of her new single. Bonnie would perform “Yes I Love You Only” in the movie Killers Three, a low-budget A.I.P. drive-in flick that featured Merle in an acting role (the song was also released on the Killers Three, soundtrack album on Capitol). The A-side, “How Can Our Cheatin’ Be Wrong,” another Dallas Frazier–penned tune, was recorded in March 1968 at a session that yielded three Bonnie songs, which would be used on her next album and one Haggard vocal, his cover of Onie Wheeler’s “Run ‘Em Off.”

A major factor that played into fewer Bonnie Owens recordings was Merle’s new status as country music’s biggest star. While Merle did session after session in May, June, and August 1968—eleven in a row, resulting in the monster number-one hits “Mama Tried” and “I Take a Lot Of Pride in What I Am”—Bonnie was not allowed to record any of her own material until September of that year, and then only three songs, enough to make up one new single release.

The session in September resulted in three songs: an Ernest Tubb cover, “I’ll Always Be Glad to Take You Back,” a Marty Robbins cover, “I Couldn’t Keep from Crying,” and a song written by sometime–Haggard bassist Leon Copeland, “Lead Me On.” “Lead Me On” was issued as the A-side of Bonnie’s next single in December 1968, with “I’ll Always Be Glad to Take You Back” as the flip side.

Merle Haggard’s opinion is that “Lead Me On” was Bonnie’s greatest chance for a chart topper: “I think that ‘Lead Me On’ was probably the closest she ever got to a hit. It had all the elements of a hit, and it sounded like a hit to me. But she had the bad luck of being covered by Conway and Loretta, and that kinda ruined her chances.”

It’s hard to say why “Lead Me On” didn’t click for Bonnie, but the Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn cover of it probably didn’t hurt her chances. Bonnie’s version was released in December 1968, and although they would take the song to number one on the country charts, Conway and Loretta’s version didn’t come out until 1971 (Norma Jean, Porter Wagoner’s pre–Dolly Parton backup singer, would also cover the song in 1972). Although Bonnie’s version was not the breakout hit Merle and Bonnie thought it would be, it was successful enough that Capitol chose to use it as the title track for her next album.

Bonnie’s fourth album, Lead Me On, was released in March 1969. By examining the session sheets, it appears to have been pieced together from a hodgepodge of sources. Half of it was taken from the three sessions she did in 1968, and the rest was cobbled together using leftover tracks dating as far back as 1965. Perhaps Capitol rushed the album thinking Lead Me On was going to be a hit; Ken Nelson doesn’t remember exactly what the reasoning was.

“Merry-Go-Round of Love” was a Buck Owens number that Bonnie recorded in August 1965 and released as a non-LP single in March 1966, coupled with “Livin’ on Your Love,” a Merle and Bonnie collaboration that she recorded in December 1965. Why these numbers weren’t included on the earlier albums is unknown, but nearly four years later they were added to the Lead Me On LP.

Other previously recorded tracks that saw the light of day on the new album were “The Back of My Hand,” a song written by Merle, and “Number 82,” written by Bakersfield songsmith and good friend Dallas Frazier, both of which had been recorded in September 1967.

The four songs from the other two previously released singles, “How Can Our Cheatin’ Be Wrong,” “Yes I Love You Only,” “Lead Me On,” and “I’ll Always Be Glad to Take You Back,” were all included on the new album. The meager release contained only eleven tracks, the previous nine rounded out by just two more numbers, Marty Robbins’s “I Couldn’t Keep from Cryin’” and another song from Merle’s pen, “I’ll Look Over You.”

One unreleased number from the March 1968 sessions, “When Billy Comes Home to Arkansas,” written by Alex Harvey (the country-western Alex Harvey, not the “Sensational” Alex Harvey), is heard here for the first time.

As if to make up for the careless way the Lead Me On album was put together, the next Bonnie Owens recordings would take place under entirely different circumstances. For the first time since she and Merle had signed to Capitol, Bonnie recorded for three days in a row at the Capitol Tower without being tacked onto a Merle Haggard session. A month after Merle had recorded another monster hit, “Workin’ Man Blues,” over June 10–12, 1969, Bonnie recorded nine tracks in a marathon effort to get enough songs together for a new album and some new singles. A few weeks later Fuzzy Owen took the tapes to Nashville to overdub a vocal background chorus. Perhaps this was a trial effort for the technique, as barely a month later Fuzzy and Merle brought the tapes of Merle’s “Okie from Muskogee” to Nashville to overdub nylon-string guitar with Jerry Reed. In mid-July Bonnie returned to the Capitol Tower to cut one more track to finish the album.

“Hi-Fi to Cry By,” a number written by legendary Texas singer, songwriter, and comedian “Bozo” Darnell (fresh from cowriting several hits with Waylon Jennings), was expected to be the hot ticket. It was released as a single, Capitol 2586, coupled with a Mary Taylor number, “It Don’t Take Much to Make Me Cry,” in August 1969.

Hi-Fi to Cry By would also be the title of Bonnie’s next album, released in November 1969. Besides the two songs that had already been released as a single, the album had an array of others from an interesting group of sources. Oddly enough, this would be the first Bonnie Owens album without any songs written by her or Merle, or any other Bakersfield songwriters, for that matter.

Lola Jean Dillon, a singer who found her greatest success writing songs for artists such as Dolly Parton, Norma Jean, and Loretta Lynn (and who cowrote the classic Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn number “You’re the Reason Our Kids Are Ugly”), landed two songs, “Now I Lay Me Down To Sleep Alone” and “I’ll Kiss My Wedding Ring Goodbye.” An old number by big-band leader Wayne King (aka “The Waltz King”), “That Little Boy of Mine,” was covered and given the Bakersfield treatment.

More covers were tackled, including “Jealous Heart,” the song written by Jenny Lou Carson and made into a huge hit by Tex Ritter in 1945; another dip into the Hank Williams songbook turned up “I Don’t Care if Tomorrow Never Comes”; and even Jim Reeves’s “How Many” was given a new arrangement.

“What Else Can I Do” was written by Earl Poole Ball, a gifted piano player who had come up through the ranks in Mississippi and Texas before moving to Los Angeles and becoming a session pianist and sometime producer for Capitol Records, where he produced Merle’s tribute album to Bob Wills and Bonnie’s gospel album (and made country-rock history by playing on records by the Byrds and Gram Parsons, including the Byrds legendary Sweethearts of the Rodeo album).

“Philadelphia Lawyer” was written by the legendary folkie Woody Guthrie, but undoubtedly when Bonnie Owens tackled it, she had Rose Maddox in mind. “Philadelphia Lawyer” was perhaps the biggest hit the Maddox Brothers and Rose ever had, and it was Rose Maddox’s signature number. It was the next song Capitol released as a single, in January 1970, coupled with “That Little Boy of Mine.” It was also the last Bonnie Owens single Capitol ever released.

“Philadelphia Lawyer” continued to be a staple for Bonnie Owens at Merle Haggard shows. The hit Haggard album The Fightin’ Side of Me—”Live” in Philadelphia album contains a live version of the song in which Bonnie uncharacteristically forgets the words.

When asked why this version was left on the album, with Bonnie’s fumbles, Merle responded in typical candor: “I left it on there because it was spontaneous; it was a live album and that made it seem more live, more real. And it was so out of character for Bonnie to forget lyrics, because that was usually my job! We left it on there because it was as real as it could be.”

Hi-Fi to Cry By contained only ten songs and wasn’t even a half-hour long. It failed to make the charts, the second album in a row to do so. The writing may have been on the wall for Bonnie Owens as a solo artist, and whether or not she sensed it going in to making her gospel album, it was to be her last recording for Capitol.

Ken Nelson had always had faith in Bonnie, but the truth was that her records weren’t selling. When that happened, he could only persist for so long before the accounting department at Capitol Records would tell him that he had to drop an artist from the roster.

Mother’s Favorite Hymns was Bonnie Owens’s last record for Capitol. There would be no singles issued from this album. As gospel albums go, this was a classic example—commercially unsuccessful, released without fanfare or promotion, seemingly produced only to satisfy the artist’s own personal desire. It was recorded in March 1970 and released in September of that year, and without so much as a whimper it marked the ending of Bonnie Owens seventeen-year solo recording career.

Mother’s Favorite Hymns was produced by Earl Poole Ball (one month before he produced Merle’s homage to Bob Wills, Tribute to the Best Damn Fiddle Player in the World) and recorded with the nucleus of what would become the new lineup of Merle Haggard’s Strangers for the next few years. Roy Nichols and Norm Hamlet remained from before, Roy now the only original Stranger left. The new rhythm section included “Bobby Wayne” Edrington on rhythm guitar, Dennis Hromek on bass, and Clair “Biff” Adam on drums, all of whom had been drafted up through the ranks of the Palomino Club house band in Los Angeles (like the first lineup of the Strangers, Wayne and Hromek had spent time in Wynn Stewart’s band, the Tourists). A short-lived auxiliary guitarist for the Strangers, Hollis DeLaughter, was also on the session, as well as consummate session piano man Glen D. Hardin. Background vocals were overdubbed later.

The songs included old standards such as “I’ll Fly Away” (written by Albert Brumley, who by coincidence was the father of longtime Buck Owens steel guitar man Tom Brumley), “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” “Where Could I Go but to the Lord,” “Gathering Flowers (For the Master’s Bouquet),” “Where We’ll Never Grow Old,” “Farther Along,” and the old traditional public domain number “Where the Soul Never Dies.”

Bonnie recut (the only song she ever recorded three times) “Wait a Little Longer, Please Jesus.” The lone secular song on the album was “Medals for Mothers,” written by Betty Sue Perry, and a cover of the Hank Williams classic “I Saw the Light” rounded things out.

It was a fine album, as gospel albums go, but sadly it marked the end of Bonnie’s career as a solo artist on Capitol Records. It was by no means, however, an end to Bonnie’s career as a singer, and by no means an end to her association with Merle Haggard or Merle’s association with Capitol, but Bonnie would not release anything under her own name for many, many more years to come.

The last track included on this set in an unreleased version of Bob Wills’s “Faded Love,” cut in August 1971 on the same day that Merle recorded “Daddy Frank (The Guitar Man).” It’s a bit curious why this song was recorded at all, since Merle had already done a Bob Wills tribute album the year before. We’ll never know what the reason was, but the track has remained in the vaults until now.

As Merle put it in his interview with the Orlando Sentinel: “Bonnie sort of dropped the torch of her own career to stoke mine.”

PART SEVEN: LIFE AFTER THE SOLO RECORDS

Bonnie continued the maniacal pace of touring with Merle Haggard and the Strangers for several more years. She seemed to be happy to be wife, harmony singer, and den mother for the troupe. No one remembers her complaining about her solo recordings coming to a halt.

The fact of the matter is that the Haggard organization was so busy and so successful during this time that more than likely no one around her bothered to ask Bonnie how she felt. It was the golden era for Merle Haggard and the Strangers, and Bonnie was part of it, even if her solo career was over.

It was a well-known fact even at the time that Merle cheated on Bonnie during these years. Bonnie knew it; she and Merle had an “agreement.” As Merle recalled in his House of Memories autobiography: “I would sit around in jam sessions on the bus until Bonnie got sleepy and went to her room. Then I’d quickly break up the session so that I could get with some gal who was waiting for me.

“I don’t know why I went through that charade. Bonnie had been around the business and me. She had seen me cheat on Leona, and she had seen other guys in the band cheat on their wives. Bonnie and I even had an agreement. She said she knew I would never change, that I’d never be faithful to one woman. But she asked, ‘Please don’t flaunt your encounters so that I look foolish.’ I didn’t flaunt them. And what happened on the road stayed on the road. I loved Bonnie very much.”

One infatuation that Merle had, though it went unconsummated, was an obvious and overt crush on Dolly Parton. Merle had known about Dolly for a long time, even cutting her song “In the Good Old Days (When Times Were Bad)” back in 1968, but by the early 1970s his obsession with Dolly was getting dangerous. In his Sing Me Back Home autobiography, Merle recounts calling Dolly at three in the morning, waking up her husband and singing his newly written “Always Wanting You” to her over the phone. Such shenanigans were politely tolerated by Dolly, but Merle’s obsession was beginning to be obvious to all parties involved, including Bonnie.

The strain of the road was beginning to get to Bonnie, as well. Touring can be rough on a young body, and Bonnie was now in her forties, significantly older than Merle and the rest of the guys in the band. Just looking at the pictures of Bonnie through these years, it is clear that the strain of the road definitely took its toll. Before she started to tour full-time, Bonnie looked like a young woman, but by the early 1970s her face began to show the worry lines and wrinkles of a middle-aged woman.

Whatever the reason, by 1974 Bonnie Owens couldn’t take any more. She stayed at home with Merle’s kids, and a year later she sued for legal separation. The divorce didn’t become official until 1978, when Merle wed thesinger Leona Williams. In the interim Merle tried to find female vocalists to replace Bonnie, including Louise Mandrell, Cheryl Rogers, and Donna Faye. Leona Williams toured with the organization during her and Merle’s turbulent romance and short-lived marriage, but none of these women had Bonnie’s presence or her ability to harmonize so perfectly with Merle. Merle had also lost his valuable songwriting partner. “I’m sure I lost a lot of good songs during that period,” Merle confesses.

After a couple of years off the road and out of the limelight, Bonnie began to miss show business. She rejoined ex-husband Buck Owens for some shows in 1978, but not long after that she rejoined the Merle Haggard touring organization as Merle’s singing partner and ex-wife. She remained with Merle throughout the 1980s. She eventually remarried, to a man named Fred McMillen who worked for an oil company, and who as a function of his job lived in Saudi Arabia for half of every year. This was a fine arrangement with Bonnie, as she liked her independence. Fred and Bonnie lived in Gardnerville, Nevada, then Ridgecrest, California, and then eventually tiny Shell Knob, Missouri. Once Bonnie was in Missouri, she again quit touring with Merle from 1991 until 1994, when the call of the road once again beckoned. She rejoined him on the road and flew back to Missouri to spend time with Fred whenever she could.

Merle Haggard remembers: “We played a lot of big fairs and a lot of big parks during the last forty years. Bonnie was always the first one out of the bus to go over and talk to the old lady, or the older gentleman. Her role was to go seek out the ones that nobody was paying attention to, and she was just perfect at that.”

During this time Bonnie finally started to get some recognition for her own accomplishments. She wrote a new original called “Startin’ Today” that would become her theme song. A self-released Best of Bonnie Owens, a compilation of her earlier songs, came out in 1990.

Bonnie lent her voice to a few other projects, including several with local Los Angeles singer Kathy Robertson. On Robertson’s 1996 disc At the Cantina she finally recorded “Startin’ Today” and added vocals to several other songs. She also contributed to six cuts on Robertson’s To Roy Nichols with Love tribute CD from 1997. They were the last recordings Bonnie Owens ever made.

Laura Cantrell, an East Coast singer with a penchant for Bakersfield-style country, recorded a poignant tribute to Bonnie with her song “Queen of the Coast” for her Not the Tremblin’ Kind disc in 2000, a fitting tribute to a woman who influenced countless other female singers.

PART EIGHT: THE FINAL YEARS

Bonnie was a natural-born road warrior. Even throughout her sixties and into her seventies she was still the valiant trouper, out there every night singing with Merle. In the late 1990s Bonnie started to get, for lack of a better word, “forgetful.” It was rarely when she was on stage—she still remembered the words to every song. It was more the little things, like forgetting her hotel room number, or forgetting to take her medications. Nobody thought much of the lapses until one of Bonnie’s neighbors back in Missouri called Buddy Alan Owens to report that Bonnie’s forgetful behavior was getting serious. Sadly, it turned out to be Alzheimer’s disease, and it was getting worse.

Michael Owens: “Mom always told us that she was happy with her life, and her career, and her boys, and how everything turned out. She also said that she wanted to die on the road.”

Bonnie may have wanted to die on the road, but the fact was that she just wasn’t able to tour anymore. After much resistance to the idea, she left the road and went back to Missouri. As the disease progressed, she eventually returned to Bakersfield to live with Fuzzy and Phyllis Owen for a while, and then ultimately required care in a senior home in Bakersfield. Phyllis Owen, who had been one of her closest friends over the years, became Bonnie’s caregiver during these last years, visiting her every day.

Buddy Alan Owens: “Mom liked the room at the senior home because it looked like a hotel room, and it sort of made her feel like she was still on the road.”

Barely a month after her ex-husband Buck Owens died, Bonnie finally succumbed to her disease, and passed away on April 24, 2006, in Bakersfield. She had made plans long in advance to be buried in Buck’s family crypt (a freestanding crypt in the Greenlawn Cemetery called “Buck’s Place”), so that she and her boys could be laid to rest together someday.

In Bakersfield, when Buck Owens passed away it was as if the Wizard of Oz had died. Buck had a star-studded funeral, replete with twenty-one-gun salute, and the newspaper ran front-page stories for a week. Bonnie’s passing a month later received considerably less fanfare, but was no less the end of an era in Bakersfield.

POSTSCRIPT

“She was the queen of the barroom singers,” according to Merle Haggard. “She may never have made it to superstardom, or become a household name, but you put Bonnie in a smoky club and there was just nobody better.”

Such may be the ultimate epitaph for Bonnie Owens. While other female country singers have been bigger stars, few made the impact or left the legacy of Bonnie Owens. Between the recordings that she made on her own and the vast number of records she made with Merle Haggard, she may be the most prolific female country singer of all time.

How can somebody exist in the world of barrooms, back stages, concert halls, dressing rooms, tour buses, truck stops, and country music for more than forty years and still be described as the nicest person in the world?

“Bonnie was . . . something special,” replied Merle Haggard, choking up in mid-sentence. He didn’t need to say anything more, because he had said it all.

Deke Dickerson

Northridge, California, April 2007

Thanks to Merle Haggard, Fuzzy and Phyllis Owen, Norm and Pat Hamlett, Buddy Alan Owens, Michael Owens, Red Simpson, Michael Nichols, Loretta Owens, Betty Bryant, Glenn J. Pogatchnik, Jason Odd, Jeremy Tepper, and Laura Cantrell.

Interviews:

Merle Haggard, December 2006

Buddy Alan and Michael Owens, January 2007

Ken Nelson, January 2007

Fuzzy Owen, January 2007

Norm Hamlet, January 2007

Red Simpson, January 2007

James Burton, January 2007

Loretta Owens, March 2007

Betty Bryant, March 2007