Yesterday I drove up to Ridgecrest, on the edge of China Lake (where the Navy has their Naval Air Weapons base), close to Death Valley. You don’t accidentally go to Ridgecrest. It’s a town on the edge of nowhere out in the hot California desert.

My friend Scotty Broyles lived in Ridgecrest. Many of you knew and loved Scotty from his many appearances on my shows at Viva Las Vegas and around Southern California and Portland and Seattle. Scotty passed away at the beginning of the year at age ninety-six, and I had to make the trek one more time.

William Horace “Scotty” Broyles was one of my favorite humans. When I was writing the story about Jim Harvey’s Bigsby-influenced musical instruments made in the San Diego area in the 1950s, I received a tip from researcher Andrew Brown about a Texas Western swing musician who had been in the Navy in California in the early 1950s. I was told that I needed to track down Scotty Broyles to see the color slide photographs he had taken of country music shows in the 1950s, and his custom-made Jim Harvey mandolin.

I had no idea what to expect the first time I drove up to Ridgecrest to meet Scotty and his wife, Betty. I knew about his Harvey mandolin and I hoped that he might be willing to sell it to me. I was surprised, when he opened the door, at how tiny he was; he was five feet tall on a good day. His voice was sharp, and he had excellent diction. His voice had a gentle Texas lilt; I can still hear it in my head. I soon learned Scotty was tough as nails and could do anything; he never let his small size stop him.

Scotty and I hit it off right away, talking about old hillbilly music and our favorite musicians. He brought out his slides and they were fantastic—beautifully shot, full-color slides of country music shows in California and Texas in the early 1950s, when nobody was shooting color photography at country music shows.

Scotty showed me around his world on this first visit—his three giant pistachio trees and a row of blackberry bushes in his backyard; an enormous sixty-year-old Mojave desert tortoise he cared for; his running trophies (he was heavily involved in running the second half of his life); his wife Betty’s sewing room setup (Betty was an excellent seamstress—she made my daughter Evelyn a beautiful quilt when she was born); his collection of guns. I stayed overnight, and in the morning Scotty woke me up at 6 am and did a hundred pushups in front of me as I sipped my first cup of coffee. I remember thinking, These Navy guys are tough. Eventually, we got around to talking about Jim Harvey and the mandolin he had made Scotty while he was in the Navy in 1951–52.

I wrote a very long piece, “Tough Old Men and Birdseye Maple,” about Jim Harvey’s musical instruments in the Fretboard Journal, and the piece was reprinted in my book Strat in the Attic. Jim Harvey was a career Navy man who lived in La Jolla, California. He loved country and Hawaiian music and built himself an electric guitar after seeing Merle Travis perform with his Bigsby solidbody guitar at the Bostonia Ballroom in El Cajon.

Jim Harvey was not your typical garage builder. He was an experienced woodworker, a man who built his own weekend getaway house in the mountains (complete with handcrafted bird’s-eye maple kitchen cabinets). When he made up his mind to build musical instruments, he made exquisitely crafted guitars and mandolins. The instruments played incredibly well, sounded great, and looked amazing.

Jim Harvey was highly influenced by Paul Bigsby. His instruments shared the natural bird’s-eye maple finishes and polished aluminum hardware that Bigsby had pioneered. A few of Jim Harvey’s instruments even sported Bigsby pickups, bought directly from the man himself at his Downey workshop. Jim Harvey knew Paul Bigsby personally. But Jim Harvey’s instruments weren’t mere copies. He had his own refined sense of style, with beautifully drawn body lines. All the Jim Harvey instruments carry their own je ne sais quoi. The man had his own ideas and his own cool visual style. Jim Harvey began to make instruments for his Navy buddies in 1951 and made approximately fifteen electric guitars, electric mandolins, and one acoustic guitar through the 1950s, with one or two additional instruments in the 1960s.

Scotty Broyles was one of those Navy buddies. Scotty was born in Mesquite, Texas, on August 8, 1928, and was raised in a musical family. He began playing mandolin and guitar at a very young age and received an A-series Gibson mandolin from his father in 1939. Scotty’s childhood scrapbook reveals that he was a fan of the Light Crust Playboys, and he learned to play mandolin in the Texas fiddle band style (a style that would come to be known as Western swing).

Scotty met his future wife, Betty McWilliams, in Dallas in 1948. Scotty wasn’t quite old enough to serve in World War II, but he enlisted in the Navy and found himself plucked out of Texas and stationed at the Naval base in San Diego during the Korean War. Scotty led a paradise kind of Southern California existence during these years, something straight out of a novel about that place at that time. He rode an Indian Scout motorcycle, co-owned and flew a small plane, and played music. Lots and lots of music. Scotty loved music. The weather was great and the state wasn’t overpopulated yet, and all dreams seemed within reach.

San Diego was a thriving country music capital in the early 1950s. The Bostonia Ballroom in nearby El Cajon brought every well-known country music star through town, and the house band was led by Smokey Rogers, with most of Tex Williams’s band in the lineup, including Cactus Soldi on fiddle and Joaquin Murphy on steel guitar. These men had all played with Spade Cooley in the early and mid-1940s, then defected to Tex Williams’s band in 1947 (they recorded his million-selling hit, “Smoke Smoke Smoke (That Cigarette)” with Tex) and became part of Smokey Rogers’s house band in the early 1950s, when he landed the steady gig at the Bostonia.

Scotty befriended Jim Harvey at the Naval base, and soon the two were attending shows at the Bostonia Ballroom on a regular basis. Scotty was teaching himself photography at the time, and in addition to shooting desert scenes and family trips, he shot color slide film at country music shows at the Bostonia.

Scotty photographed Merle Travis (“My camera wasn’t working correctly that night, so in between sets I asked Merle to kneel down on the stage and hold still for a second so I could get a good shot”), Lefty Frizzell, Hank Snow, The Carlisles, Homer and Jethro, Tex Williams, Smokey Rogers, and others at the Bostonia. During the same timeframe, Scotty and Jim also went to Los Angeles to the Hometown Jamboree show, where Scotty photographed Speedy West and Jimmy Bryant, Cliffie Stone, Harry Rodkay, Hank Penny, and others. Many years later, I was able to get Scotty’s excellent photographs in many Bear Family box sets and CD reissues, and on the cover of my Merle Travis book, 16 Tons. His photos were extraordinary, and his clear, in-focus color photography brings that early-1950s era to life at a time where nobody thought country music was important enough to splurge on color slide film.

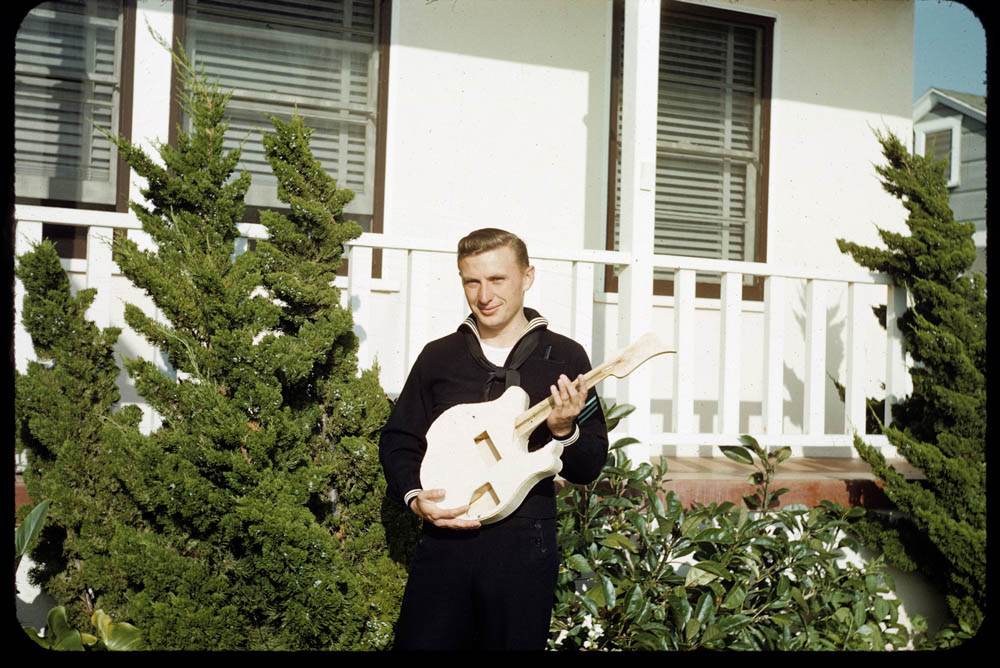

Scotty was impressed by Jim Harvey’s handiwork. At that point, Jim had made several guitars and a steel guitar (including a unique Bigsby-style guitar for Robert “Bob” Tuvell, with a DeArmond floating pickup, an instrument that was the first Harvey instrument I was able to find) for several of the men in their Naval unit. Scotty asked Jim Harvey to make an electric mandolin for him in 1951. Scotty designed the body shape himself (the only Harvey instrument not explicitly designed by Jim Harvey). Scotty did not play his mandolin in the typical, Appalachian bluegrass style. Scotty played single-string melody and improvisational lines over pop and jazz and country standards (he had learned this style from other Texas musicians he watched growing up—Leo Raley with Milton Brown’s Musical Brownies, Paul Buskirk from Houston, and Tiny Moore, who played with Moon Mullican in Texas before joining Bob Wills’s band in the mid-1940s). Because of his unorthodox playing style, Scotty also had a few out-of-the-ordinary ideas. For instance he wanted his electric mandolin to have five single strings (with a low C on the bottom), instead of a mandolin’s standard eight strings (Scotty got this idea from Paul Buskirk, who had a ten-string mandolin with a low C). Scotty also wanted a five-pole Bigsby pickup installed.

Scotty and Jim Harvey drove up to Paul Bigsby’s workshop in Downey, California, and told him of their plan to install a Bigsby pickup on Scotty’s mandolin. Bigsby told them he would have to inspect Jim’s work to make sure it was sufficient to his standards. Jim brought in Scotty’s unfinished mandolin, and Bigsby thought the workmanship was very good. The pair left Scotty’s mandolin there for Bigsby to personally install the pickup. Scotty recalled that a Bigsby pickup cost fifty dollars in 1952 (more than a week’s pay), and the price was the same whether Bigsby installed it or if you did the work yourself.

(A side note for country music historians: Tiny Moore, who played with Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys and his brother’s band, Billy Jack Wills’s Western Swing Band, ordered a Bigsby electric mandolin, and his mandolin was half-finished when Tiny saw Scotty’s five-string Harvey mandolin sitting in Bigsby’s shop, awaiting the pickup installation. Tiny’s mandolin was originally constructed to be a four-string mandolin, but after seeing Scotty’s, Tiny insisted his be a five-string as well. This apparently annoyed Paul Bigsby, as the fretboard width was narrow and he hadn’t planned on it, but Tiny Moore’s Bigsby mandolin was finished as a five-string mandolin and was used on many historic recordings, including his latter-day career as one of Merle Haggard’s sidemen).

Jim Harvey completed Scotty’s mandolin in 1952, and Harvey built a special double-compartment case at Scotty’s request that would house both the Harvey electric mandolin and his Gibson mandolin. Scotty later told me he regretted that decision, as the double case was quite large and heavy, and for the decades leading to his death, Scotty had his Gibson mandolin in a separate case, and his Harvey mandolin in a lightweight gig bag made by his wife Betty.

Scotty and Betty had three children: John, Judy, and Jamie. The family moved around quite a bit, following Scotty’s various jobs. For several years in the mid-to-late 1950s, Scotty and his family lived in Houston, where Scotty obtained a bachelor’s degree from the University of Houston, and rekindled his friendship with mandolin and guitar virtuoso Paul Buskirk.

Paul Buskirk is one of the greatest American musicians you may not be aware of. He is perhaps most famous for getting Willie Nelson’s career off the ground in the 1950s, employing Willie as a guitar teacher at his music school. (Willie later gave this great quote: “I wasn’t a good guitarist, but I kept one lesson ahead of the students.”) Nelson’s first recording of “Night Life” listed the recording artist as “Paul Buskirk and his Little Men, featuring Hugh Nelson, vocals.” Buskirk’s playing on mandolin, mandola, and guitar (Buskirk played guitar, but usually tuned it like a mandolin) was so frighteningly fast and accurate and musical, he was considered the best in the Houston area. Buskirk worked with LuLu Belle and Scotty and ex–Bob Wills steel guitarist Herb Remington, as well as performing as a backing musician for many touring acts that came through Houston.

Paul Buskirk had a Bigsby ten-string electric mandolin, and for a time played a Fender Stratocaster with a Bigsby-made mandola scale neck (this instrument is unfortunately lost to time). In 1956, with rock ’n’ roll taking over the country and the mandolin becoming an outdated and unpopular instrument, Buskirk wrote to Paul Bigsby asking him to make a doubleneck electric guitar. Paul Bigsby wrote Buskirk a return letter saying that Bigsby vibratos were now his exclusive business and he was no longer accepting orders for electric guitars.

Buskirk was mad. He was used to getting his way. Scotty told Buskirk about his friend Jim Harvey in San Diego, and suggested that he might be willing to make him the doubleneck he wanted.

On Scotty’s suggestion, Jim Harvey began work on the Paul Buskirk doubleneck in 1956, and the instrument was completed in 1958. The Buskirk doubleneck was Jim Harvey’s wildest, most ornate and over-the-top instrument. It looked Bigsby-esque, but because Buskirk was still upset with Bigsby over his snubbing, he insisted that the doubleneck have Stratocaster pickups, and even though the instrument had two Bigsby vibratos on it, Buskirk insisted that the Bigsby name be covered by decorative plates. Buskirk’s doubleneck (and most of the other Harvey instruments) were inlaid with mother-of-pearl that Jim Harvey harvested himself, diving for abalone shells off the beach in La Jolla.

Buskirk used the doubleneck guitar on Willie Nelson’s first recording of “Night Life,” on many recordings he made with Herb Remington (check out the Herb Remington album Steel Guitar Holiday for some incredible Buskirk-Remington twin guitar work), a Paul Buskirk solo album called Paul Buskirk Plays a Dozen Strings (featuring the instrumental “Jim Harvey’s Rag”), and many of Willie Nelson’s later recordings in the 1970s, when Buskirk rejoined Nelson’s band.

This post is already getting long, but the saga of Paul Buskirk’s doubleneck Jim Harvey guitar is detailed in my “Tough Old Men and Birdseye Maple” story. The short version of the story is that the guitar was stolen from Buskirk in the 1970s and kept in the thieves’ hot car trunk, but then returned to him several years later by a pawnshop owner who confiscated it from the thieves when they tried to pawn it. The guitar was later stored under a dripping air conditioner in Buskirk’s mobile home in Nacogdoches, and the case was destroyed and the doubleneck damaged. When Buskirk died, the guitar was willed to his friend Huey Wilkinson, who kept it for many years with plans to restore it. Eventually I tracked down Huey and asked to see the instrument. Huey gave it to me with the condition that I restore it to its former glory. Garrett Immel did an incredible restoration on the instrument, and most recently the doubleneck was displayed at the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville in their Outlaws and Armadillos special exhibit, next to Willie Nelson’s tennis shoes. Through my friend Kevin Smith, who plays bass for Willie, I was able to take the guitar onto Willie’s bus and show it to him at a California tour stop a few years ago. Willie remembered the instrument well—who wouldn’t?

Scotty and his family moved constantly through the years, with jobs in Lawndale, Boise, Houston, Camarillo, Carson City, and eventually Ridgecrest, California. Ridgecrest would be home to the Broyles family for the last fifty years of his life. Scotty continued to play his Harvey mandolin with a local group called Cross Current, and quietly led a life filled with his family and other hobbies—running (he ran marathons with a group called the “Over the Hill Track Club,”) church activities, fishing, motorcycle riding, and camping. Scotty even summited Mount Whitney several times.

On our first visit, Scotty indulged all my questions about his history and the history of Harvey instruments. I had brought Rob Tuvell’s Harvey guitar to show him, and when I was finished with all my questions, Scotty said: “Let’s pick.”

I accompanied Scotty on a tremendous batch of songs. He sang popular songs like “Just Because” and “San Antonio Rose.” He picked endless instrumental rags, waltzes, Schottisches, and fiddle tunes. If I didn’t know the song, he would yell out “Dill Pickle Rag, in the key of D!” and then launch into it, expecting me to figure out the chords. He was entertaining, he was hilarious, and he was charming. I loved Scotty from the get-go. He didn’t know it, but Scotty was star material. He was a natural.

I went to Ridgecrest that first time hoping that Scotty would sell me his mandolin, but I left his home just wishing that I could hear Scotty play his mandolin just a little bit more. It was incredible to see a man playing an instrument that had been custom made for him decades earlier, with his own hands wearing lasting impressions on the back of the neck and on the tailpiece, where he placed his hands as he played the mandolin for 100,000 hours over the course of seven decades.

Most of you know what transpired in the next eighteen years after my first visit with Scotty. I published the Jim Harvey story, and we did two reunions of Jim Harvey instruments, in Las Vegas and Anaheim. Scotty was the hit of the shows, and we continued to bring him back every year to Viva Las Vegas to perform at both my Guitar Geek shows and the Dave and Deke Hillbillyfest show. Scotty was loved by all who saw him perform. He got into character, dressing up in his sharp Western suits for the Guitar Geek shows and in full hillbilly comedy attire for the Hillbillyfest shows. He played mandolin and showed off his banjo skills too (he was quite good at both tenor banjo and five-string banjo, performing duets with Mitch Polzak at Hillbillyfest on the latter).

Scotty often received standing ovations, and his comic timing was perfect. He’d wait until the applause would die down, then he’d say in the microphone: “Aww, you all are only clapping for me because all the good players died!” Scotty was a hoot, man. He kept everybody laughing. We all loved him and were so happy to have him at our shows. Scotty wanted to do anything we could use him for, so I brought him along for shows in Portland and Seattle and Los Angeles and San Diego with an all-star Western Swing band.

It was a challenge but also a fun experience to bring along a nonagenarian on these driving trips. I remember Scotty telling stories about obscure hillbilly musicians he had worked with and seen back in the day (people like Claude Gray, Smokey Stover, Gene O’Quin, Merrill Moore, and Roy Hogsed). He would be absolutely flabbergasted when I told him I had all their music on my phone. He’d speak of seeing Roy Hogsed performing in San Diego with his trio in 1952 in San Diego, and the next thing you knew, we’d be listening to Roy Hogsed on my phone in the car. Scotty couldn’t believe modern technology could do that, and the look of wonder in his eyes is something I’ll treasure when that music he hadn’t heard in close to seventy years would come blasting out of my car speakers.

Eventually Scotty’s wife, Betty, went through a period of bad health, and she passed away in October 2022. She and Scotty had been married for seventy years and two months. Scotty, who for many years seemed immortal (I remember seeing a photo of Scotty, as an elderly man, riding a dirt bike motorcycle, jumping in the air, and him complaining that his family made him give up motorcycle riding when he turned eighty-five), eventually couldn’t outrun Father Time, and he began to have health and mobility problems as well. He had a massive stroke at the Thanksgiving table in November 2023, and he spent several months in the hospital and then a rehabilitation center.

Incredibly, Scotty recovered enough to perform at Viva Las Vegas in April 2024. He had to use a walker at that point. For the first time, he sat down when he performed, but he was still the same old Scotty, cracking jokes and getting the crowd going with his ribald alternate lyrics to “Sheik of Araby,” which included the audience callback “WITH NO PANTS ON!” For one last time, he got a standing ovation. It wasn’t lost on myself, Sally Jo, or any of the other musicians and audience members that Scotty looked much older and more frail than he had the year before. We knew that Scotty was finally facing mortality.

I spoke with Scotty a few more times on the phone after that, and we had already made plans for Viva Las Vegas 2025, but it wasn’t to be. My friend, William Horace “Scotty” Broyles passed away quietly on January 17, 2025, at the age of ninety-six.

In the months since Scotty passed away, I had been in touch with his kids, letting them know that I’d be interested in the mandolin if they wanted to sell it to me. We finally reached an agreement, and yesterday I drove up to Ridgecrest to meet them.

I’ll admit it, it was really sad to pull up to Scotty’s house knowing that he didn’t live there anymore. John, Judy, and Jamie had been cleaning and getting rid of stuff for months, and Scotty and Betty’s house now looked like every other house whose estate sale I might go to. I remembered Scotty doing a hundred pushups on the floor while I sipped my coffee.

After a few hours going through things and making a deal, I loaded up my car with Scotty’s Harvey electric mandolin and his Gibson mandolin, an old Gibson acoustic guitar (repainted purple by Gene Moles in Bakersfield in the 1970s, but that’s another story for another day), an old amplifier, boxes of 78 rpm records, photos, a scrapbook, a bunch of Scotty’s old Western scarves, and Scotty’s original 1950s cowboy hat and boots that he had bought in Houston.

I was happy that the family let me buy this stuff from them, and I was happy that I could keep the Jim Harvey instruments together and preserve this very important piece of California’s musical history. I was happy that I could take these things and remember my old buddy Scotty Broyles (we’ll set up a little display with his mandolin and hat and boots every year at Viva Las Vegas in his honor).

But as I left Ridgecrest, I couldn’t help thinking what I thought the very first time I drove up there to meet him. Owning the Harvey mandolin would be cool, and yesterday I got to do just that. But really, I just wanted to listen to Scotty play it, just a little bit more, and hear that soft Texas lilt to his voice.

I was reminded of the last paragraph of my “Tough Old Men and Birdseye Maple” piece I wrote back in 2007…

“In the end, what had begun as a personal quest to acquire more guitars had turned into something completely different. Getting to know these old Navy men (Scotty and Rob Tuvell), experiencing the generosity of people like Huey Wilkinson, getting to know Jim Harvey through photographs and stories from his family—this all meant a lot more to me than owning guitars. These are objects that I certainly treasure, but, more than that, they are the vessels that have led me through an important life journey during which I’ve met some amazing people—joyful people united by a common love of music. Ain’t that what’s it all about?”

See more photos at Deke’s original Facebook post!