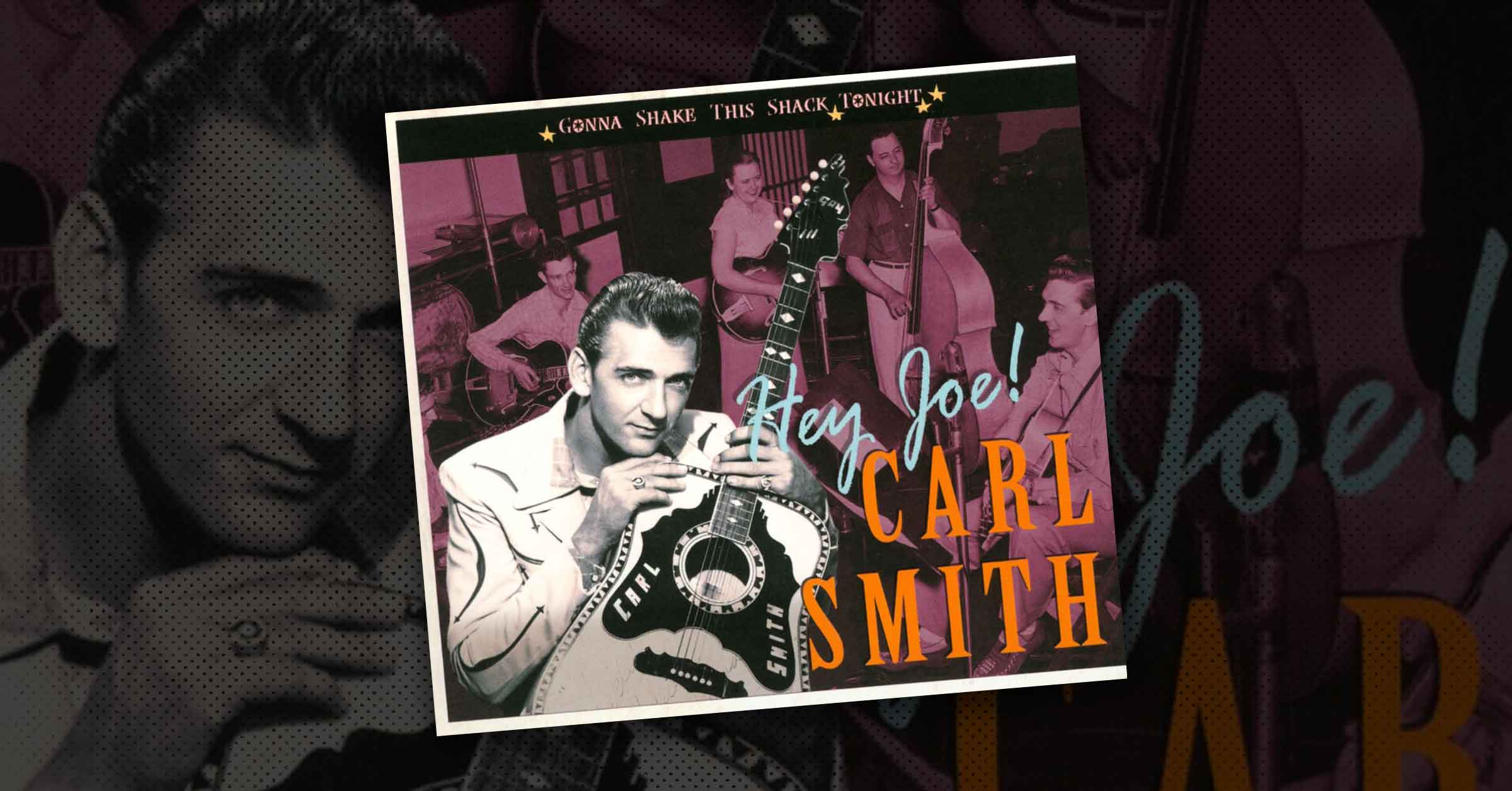

Liner notes for Carl Smith: Gonna Shake This Shack , Bear Family Records

Originally published in 2009

Of all the country music stars from the “Golden Era” of the 1950s and 1960s, no star has faded from the public consciousness more than the great Carl Smith. Although he possessed a fine voice, rugged good looks, and a string of huge hits under his belt—not to mention his induction in the Country Music Hall of Fame—Carl Smith is largely forgotten today. This compilation seeks to rectify that situation.

Perhaps it is the insatiable demand for drama and tragedy that has led to the general public adulation for outlaws like Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, and Johnny Paycheck. In the case of Carl Smith, retiring to a 500-acre ranch south of Nashville does not make for juicy gossip, and may begin to explain why Smith is such an obscure figure today.

Carl Smith was born near Maynardsville, Tennessee, on March 15, 1927. Growing up on the family farm, Smith was the youngest of eight children. Credit must be given to the determination of Smith’s parents, Dock and Ina Monroe Smith—the first seven children were girls, but they wanted a boy.

Another Maynardsville resident was Roy Acuff, who began making noise on Knoxville radio in the mid-1930s. Another future star, Chet Atkins, came from nearby Lutrell, and was also beginning to make a name for himself (playing with Bill Carlisle) over Knoxville radio. Young Carl Smith grew up listening to these men, and by the time he was ten years old, he got his first guitar. After taking guitar instruction through an outfit called “Beale’s Guitar Courses,” Smith was smitten with a desire to play music.

Even today, it would be unusual for a 13-year-old boy to take the bus by himself to go perform on the radio every week, but that’s exactly what the driven young Carl Smith did, gathering more experience any place he could. Carl did so as much as he could throughout his high school years, before enlisting in the Navy.

Carl hoped that he could get into the Special Services entertaining the troops, but the Navy felt he could do a better job supervising a mess hall. Carl spent most of his stint in the Navy making trips to and from the Philippines on a transport ship named the USS Admiral Sims.

Upon his return to Tennessee, Carl returned to his radio work, and soon began working with the most popular act in Knoxville of the day, Molly O’Day and her Cumberland Mountain Folks. Carl built up lots of experience with O’Day, playing rhythm guitar, upright bass, and singing.

After O’Day and her husband gave up music to run a family grocery for a time, Carl spent a year plagued with failure and self-doubt. The year of 1947 was spent returning to the family farm and planting tobacco, then traveling carpetbagger-style to Asheville, North Carolina; Wilmington, North Carolina; and Augusta, Georgia before returning once again to the family farm in Maynardsville. Despite a December, 1947 recording date in Nashville with Molly O’Day, things looked bleak during this time for Carl Smith.

Mid-1948 found O’Day and her group coming out of their short retirement, and they asked Carl to rejoin the group, an offer he eagerly accepted. Carl also began working with future Hee Haw star Archie Campbell’s group around the same time. It was a good time to be working in Knoxville, as the town was a hotbed of talent at the time. The Louvin Brothers, Flatt and Scruggs, Maybelle Carter and The Carter Family and many others worked the Knoxville radio circuit around this time, and all of them knew Carl and were impressed with his budding talent.

Knoxville eventually became enough of a hotbed to send Nashville talent scouts calling, and it was through a series of small, steady steps that a dobro player named Speedy Krise and an A&R man named Troy Martin played crucial roles in Carl’s big career break.

George “Speedy” Krise was the dobro player in Archie Campbells’s band, and was also a budding songwriter with a few minor hits under his belt. Speedy could write a good song, but he couldn’t sing his own songs well enough to pitch them to major artists. As a result, Speedy hired Carl to sing on the demo acetate records of his songs.

Troy Martin was an A&R man who represented the Peer-Southern publishing concern, and who had formed an alliance with Don Law of Columbia Records to scout the hottest radio areas of the country looking for new talent.

Martin came to Knoxville and was sufficiently impressed with Carl’s voice that he took some of Krise’s song-plugging acetates back to Nashville with the intent of getting Carl a Columbia recording contract.

Don Law liked what he heard on the acetates, but told Martin that he would sign Carl only if WSM would hire the singer to appear on the radio. Jack Stapp, the Grand Ol’ Opry manager, auditioned Carl and liked what he heard as well, but told Martin he would only hire Carl if he were signed to Columbia. A stand-off ensued, and Carl returned to the family farm in Maynardsville. This might have been the end of Carl’s career, but eventually Stapp relented and hired Carl for a morning show on WSM. As a result of this, Don Law signed Carl to a Columbia deal on May 5, 1950.

It was only five days after Carl signed with Columbia before he was at the Castle Studio in Nashville recording his first session for the label. The studio musicians Carl recorded with were some of the musicians he had recently been playing with on WSM. You couldn’t get better musicians at the time—on guitar was future studio ace Grady Martin, and steel guitar was handled by Billy Robinson, both of which had recently recorded with and toured with Red Foley. Second guitar duties fell to Jabbo Arrington, who would soon join ‘Little’ Jimmy Dickens Country Boys, and the bass man was Opry stalwart Ernie Newton. From the very first session Carl Smith ever recorded, he only worked with the absolute cream of the crop musicians, a standard he would keep until his retirement.

Carl had two sessions in 1950, resulting in three unsuccessful singles (none included here) before hitting paydirt on his third session.

“Let’s Live A Little,” a song written by a little-known Peer-Southern staff writer named Ruth Coletharp, released as a single with Hank Williams’ “There’s Nothing As Sweet As My Baby,” became Carl’s first hit, peaking at #3 on the Billboard charts and selling over 200,000 singles-an impressive figure in the country market in those halcyon days.

We’ve included a more rockin’ re-recording of “Let’s Live A Little” on this compilation, dating from 1958. The original is typical early 1950s country with no drums, but the version we’ve included here holds more appeal to the rockabilly and boppin’ hillbilly audience of the Gonna Shake This Shack Tonight series.

Once Carl was out of the gate, he was almost unstoppable. The hits kept coming, and Carl toured relentlessly (at first as an opening act for such stars of the day as Hank Williams and Ernest Tubb). Opry talent director Jim Denny managed Carl’s career, and he kept him working at a maniacal pace, which suited Carl just fine.

Carl Smith’s greatest years were between 1950 and 1955, where he racked up an impressive thirteen Top 10 hits. Some of these included the Number 1 hits “Don’t Just Stand There,” “Loose Talk,” “Are You Teasing Me” (written by Ira & Charlie Louvin) and his career song “Hey, Joe.” Other smashes for Carl included “Back Up, Buddy,” “Our Honeymoon,” and “Ten Thousand Drums.”

We’ve included a few of the hits on this disc. As far as the compilation you’re holding in your hands, however, the typical fan of vintage honky-tonk and rockabilly finds some of Carl Smith’s more obscure songs and forgotten album tracks much more interesting than many of his middle-of-the-road hits.

Beginning in 1951, Carl had assembled a crack road band, which he named the Tunesmiths. The Tunesmiths consisted of the excellent guitar and steel guitar combination of Sammy Pruett (recently ‘furloughed’ from Hank Williams’ Drifting Cowboys) on guitar and Johnny Siebert on steel guitar. Taking a cue from Opry musicians Grady Martin and Billy Robinson, both of who had custom-made Paul Bigsby instruments, Pruett and Siebert both ordered Bigsby guitars as well (Pruett playing an Epiphone archtop guitar with Bigsby pickups). Shortly thereafter Carl Smith would also sport a Martin acoustic guitar with a Bigsby custom neck with his name inlaid on the fretboard. Paul Bigsby’s instruments were custom built on a limited basis out of his shop in Downey, California, and in the early 1950’s, if you played a Bigsby instrument, you had truly “made it” in the country music business.

The Tunesmiths also contained the excellent rhythm guitarist Velma Williams-Smith (one of Chet Atkins’ favorite rhythm guitarists, Chet would use her on hundreds of recording sessions over the years), Roy “Junior” Huskey on upright bass (one of the best bass players in Nashville, and an old Knoxville friend of Carl’s), fiddler extraordinaire Dale Potter, and future Nashville studio superstar Buddy Harman on drums.

Together, the Tunesmiths backed Carl on his ballads and waltzes and mid-tempo numbers, but like ‘Little’ Jimmy Dickens group ‘The Country Boys,’ the Tunesmiths truly excelled at uptempo western swing and prototypical rockabilly numbers. In particular, “Go Boy Go” from 1954 is one of those classic records caught in a particular time warp—a bona fide rockabilly record made before Elvis recorded “That’s All Right, Mama,” made by musicians who would undoubtedly refute any charge that they had ever played a hand in the birth of Rock and Roll.

Also included here from the fertile 1950-55 period are such classics as “Trademark” (written by Carl’s friend Porter Wagoner), “Dog-Gone It (Baby I’m In Love),” “Lovin’ Is Livin’,” “Oh Stop!,” “More Than Anything Else,” “I Don’t Believe I Will,” “Baby I’m Ready,” “Don’t Tease Me,” “I Just Don’t Care Anymore,” and a duet of “Time’s a Wastin’” with June Carter.

The husband-wife team of Johnny Cash and June Carter is now so burned into the public consciousness that few remember June Carter’s first marriage was to another famous country singer-Carl Smith. Carl had met Mother Maybelle and the Carter Family during his Knoxville radio days, and struck up a relationship with June Carter that developed into a serious relationship when Carl and June joined the Opry at the same time in 1950. By June 1952 the pair were wed.

Carl and June had a daughter, Rebecca Carlene Smith, born in 1955. In later years Rebecca Smith would change her name professionally to Carlene Carter. Carlene (often erroneously believed to be one of Johnny Cash’s daughters) adopted the name as her stage persona, and from the late 1970s through the early 1990s had a successful country music career of her own.

Carl Smith has always been known around Nashville as a shrewd businessman, and in 1954 he partnered with Jim Denny, Webb Pierce, and Troy Martin to form the Cedarwood/Driftwood publishing company, which blossomed and became one of the biggest and most powerful concerns in Nashville. The money was huge, and Carl soon bought a 500-acre farm in Franklin, Tennessee, where he raised Black Angus cattle.

In fact, by 1956 Carl Smith was earning so much money through recordings, personal appearances and his publishing company that he could afford to quit the Opry; a notoriously low-paying gig that requires members to reserve Saturday nights for the Opry (generally the best paying night of the week).

Carl envisioned himself as a film star. For a short time, he moved to Hollywood and made two movies, The Badge Of Marshal Brennan and Buffalo Guns. Although he possessed the Marlboro Man looks of a Western film leading man, the film business never panned out for him beyond those two features.

In 1957, Carl joined the Philip Morris Roadshow, a touring country music cavalcade that had big promotional dollars behind it courtesy of the tobacco conglomerate that sponsored it. Carl joined a large cast of singers as the headlining star and stayed on the Roadshow for two years.

During this time, Carl’s marriage to June Carter had fallen apart. It was on the Roadshow that Carl met another female singing star, the then up-and-coming Goldie Hill. Carl and Goldie fell madly in love, and were married. The pair became one of Nashville’s most enduring couples, and stayed married until Goldie’s death in 2005.

After Carl’s departure from the Grand Ol’ Opry in 1956, like many of his peers he flirted with rockabilly for a brief period (his 1958 re-recording of “If Teardrops Were Pennies,” in particular, is an under-appreciated rockabilly classic, and we’ve also included near-rockabilly numbers like “No Trespassing,” “Happy Street,” “A Love Was Born,” and even Carl’s recording of the Eddie Cochran classic “Cut Across Shorty”), and even tried out material leaning in the direction of his label-mate Ray Price (“Lonely Girl” and Carl’s version of “San Antonio Rose,” both included here, exhibit a heavy Ray Price influence from Price’s late 1950s era).

As the music moved from the bouncy hillbilly of the Hank Williams era to a harder honky-tonk sound of the late 1950s, Carl Smith tried to change with the times, with varied results. Typical Nashville efforts of the era such as “That’s The Way I Like You The Best,” “I Won’t Be Mad,” “Why, Why,” “Mr. Lost,” “Take It Like A Man,” “Be Good To Her,” “It’s All My Heartache,” and “Goodnight, Mr. Sun” were all good, solid efforts, but Carl seemed to be copying others, not leading the pack.

That statement, in a nutshell, sums up the remaining years of Carl Smith’s career. The man stayed busy—he signed on to Red Foley’s successful Ozark Jubilee (later Jubilee U.S.A.) nationally syndicated television show in 1959, became a regular on the ABC-TV network show Five Star Jubilee, and beginning in 1964, had a hugely successful Canadian television show, Carl Smith’s Country Music Hall, that ran for a staggering 190 episodes. He continued recording singles and albums for Columbia Records until 1974, and sporadically for Hickory and Gusto since then. During the 1960s and 1970s, he continued to rack up chart hits, though the sales figures and chart positions would never match up to his 1950s heyday. While he kept recording, after 1959’s “Ten Thousand Drums,” which peaked at #5, only the most astute Carl Smith obsessive could name any of the minor hit records that followed, save for his last top 10 appearance in 1967 with a cover of the western song “Deep Water.”

Carl Smith is one of those rare characters in country music that made enough money and satisfied his ego enough to retire from the business a happy and contented man. Carl semi-retired in 1974 but officially called it quits in 1977. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2003, but even that couldn’t coax Carl out of retirement for a show. Since 1977 Carl Smith sightings around Nashville have been in non-music related activities, such as he and Goldie’s prize-winning show horse business in the 1970s and 1980s.

This self-imposed musical retirement may be the reason that Carl Smith, one of the greatest stars Country Music has ever known, is so forgotten today. This compilation of excellent uptempo hillbilly, honky-tonk stompers and country-flavored rockabilly seeks to jog a few memories and rectify that situation.